Would Dr. King Be Welcome To Speak at Church Today?

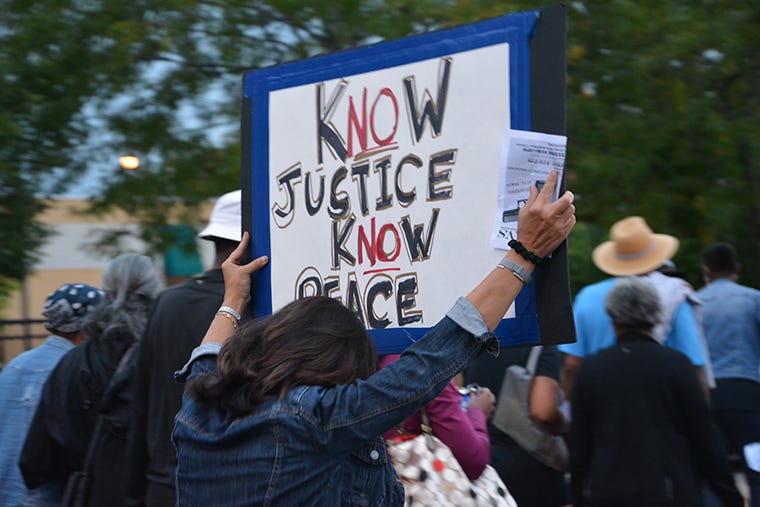

In a world awash with more 'profits' than 'prophets,' John Fountain asks if iconic civil rights leader's message would be celebrated today.

By John W. Fountain

CHICAGO, Jan. 16—If Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had lived, would he be a welcomed guest at these same churches now filled with celebratory praise for a dead Civil Rights leader?

Would he be invited to stand in their pulpits and preach reform against a backslidden, socially disconnected church that today basks in materialism while the people perish? In a land where across Chicago and other urban centers, churches dot the landscape while homicide, crime and poverty reign?

In a city where at least 695 people, according to Chicago Police were murdered last year, and at least 2,832 shot or nearly eight a day. Where the prophetic voice, with a few exceptions, has become a near whisper in a world awash with more “profits” than “prophets.” At least the church’s heart of hope, compassion and for social change cannot be heard as a body collective, crying daily without ceasing against evil and for an end to the shedding of innocent blood, for equality and social uplift the way I suspect that Dr. King’s would if he were still here.

But if he were here today on his 94th birthday, would Dr. King’s message be embraced? Or would Dr. King instead be banished for calling into question why—in this city where in 1966 he lived with his family, to bring attention to the housing plight of the poor—politicians and far too many preachers suffer laryngitis on the socioeconomic issues he once railed against?

I wonder.

‘Would he wince with piercing pain at our self-implosion and cannibalization as a race?’

Would Dr. King be eschewed for questioning why millions upon millions of dollars in Chicago alone have been spent building so-called worship centers while poor black and brown neighborhoods remain in economic crisis? Where food deserts, unemployment, drugs and homicide have become intractable tenants, and where remnants of the fires that burned on the city’s West Side soon after Dr. King’s assassination still stand as glaringly as the vacant lots of debris, garbage and rubble.

Would his fellow brethren welcome him or shun him—as history shows they did in 1964, when Mayor Richard J. Daley warned local black preachers to not allow the southern traveling rabble-rouser to speak from their pulpits or else face political repercussions?

The Reverend Dr. Clay Evans did not succumb to Mayor Daley’s intimidation and invited Dr. King to preach from his pulpit at Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church, though historical accounts show that Evans’ punishment was an eight-year delay to build a new church orchestrated by Mayor Daley. Evans chose truth, love, community. He chose what was good and right.

Today, which side of history would Black Chicago preachers be on?

I wonder.

Amid the deification of a man who history shows so many preachers stood on the sidelines of a stride toward freedom that cost him his life, I wonder. Amid the silent complicity of far too many do-nothing bling-bling preachers and politicians in our continued struggle, I wonder.

I wonder whether here, in Bigger Thomas’ town, where Black Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were gunned down as they slept, where political power still seeks to muzzle the prophetic voice, would Black preachers today turn Dr. King away rather than risk losing the favor of the current mayor?

Would they label Dr. King a troublemaker, an outside agitator come to stir up the status quo in their dear city and their comfy cozy 21st century corporatized—and too often politicized—version of Christianity?

And if Dr. King ventured beyond the city’s Magnificent Mile to its insignificant isles on the South and West Sides, where poverty ebb and flow like the mighty Mississippi River, and where public education remains largely separate and unequal, would he not be mesmerized by the general sense of complacency among the so-called moral leaders?

Would Dr. King marvel at the sheer overwhelming volume of churches in the hood from corner to corner that stand as potential symbols of hope and light, and yet seem to coexist with so much death and darkness? Would he wince with piercing pain at our self-implosion and cannibalization as a race, both in word and deeds, including that by young black men gunning down young black men on the church’s stairs during Sunday service?

And if Dr. King stood at the South Side corner of Emmitt Till Road and King Drive, would he see the fruit of the blood and sacrifice of Civil Rights icons or simply more evidence of the dream too long deferred, or perhaps worse—a mere semblance of his dream on life support?

If he listened to the milquetoast sermons of so many pie-in-the-sky preachers who do not prescribe a more social and imminent Gospel that seeks to create earthen change agents; if he saw the glitz and glam of a church in a shimmering city, where men, women and children huddle and shiver on the streets in dark corners as outcasts while so many churches stand at bay—fat with avarice and jaundiced with apostasy of love and grace; would Dr. King call the church to repentance?

I wonder.

I wonder if Dr. King might suggest that: “Today the judgment of God is upon the church for its failure to be true to its mission.” That “if the church does not recapture its prophetic zeal, it will become an irrelevant social club without moral or spiritual authority.”

I wonder if Dr. King might have the audacity to suggest that the church “as a whole has been all too negligent on the question of civil rights.” If he might be so moved as to charge that the church “has too often blessed a status quo that needed to be blasted, and reassured a social order that needed to be reformed.” To assert that “the church must acknowledge its guilt, its weak and vacillating witness, its all too frequent failure to obey the call to servanthood.”

Truth is, I don't wonder. For that is exactly what Dr. King said decades ago in his book, “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?”

And yet, 55 years since watching as a little boy from my family’s third-floor apartment window the West Side go up in flames after news of Dr. King’s assassination, I can't help but wonder why, after all this time, so much remains the same. Even at all these churches that resound today with praise in Dr. King’s name.

I suspect it’s easier to praise a dead dreamer than to embrace a despised troublemaker who stood uncompromisingly for freedom and justice and whose true legacy calls upon us to challenge the status quo and to do more than just dream.

#JusticeForJelaniDay

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com

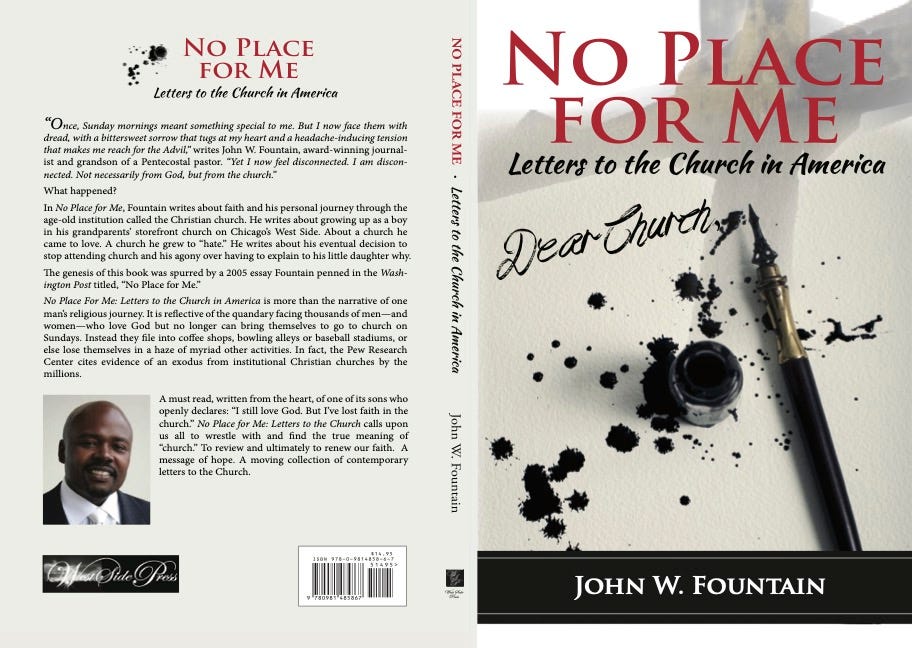

COMING THIS WEEK on 50 CENT A WORD

A three-part series, titled, Letters to The Church. The series features John Fountain’s original, uncut essay, “No Place For Me,” first published in the Washington Post in 2005, and subsequently in newspapers across the country. Soul-stirring, critically acclaimed and controversial, it is an honest dissection and exploration of the relevance of the Black church in America by a Pentecostal son of the church now disconnected, disillusioned and distanced from the church he once loved. A three-part series, this week’s offering features a letter from a prominent pastor written to Fountain in response to his essay, and also Fountain’s reply years later, his current reflections and an update now 17 years since writing his original essay and penning his book, “No Place For Me: Letters to The Church in America”