While Jury Deliberates; A Native Son Laments

A jury in a Cook County criminal court began deliberations Thursday in the case of white Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke charged…

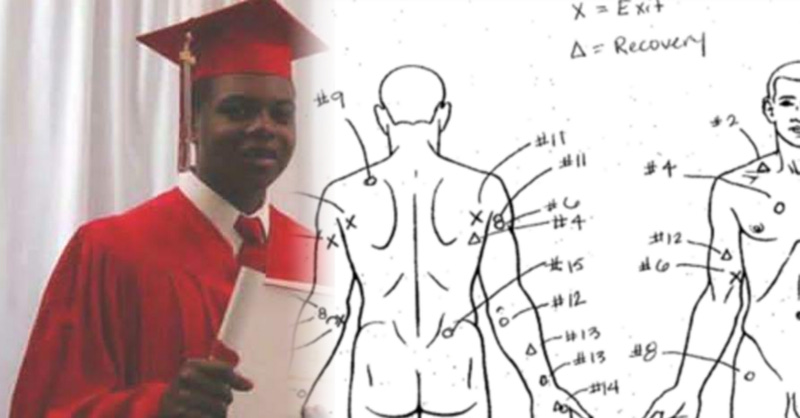

A jury in a Cook County criminal court began deliberations Thursday in the case of white Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke charged with murder in the fatal 2014 shooting of Laquan McDonald, a black 17-year-old, shot 16 times. The pending verdict in the highly charged case has the city on edge.

By John W. Fountain

CHICAGO — “Not guilty.” An acquittal is coming in the Laquan McDonald murder case. Like a rainstorm looming on the horizon, I can just feel it. I wish it were not so. Perhaps one can still hope.

I stood in the hot sun outside the George N. Leighton Criminal Court Building during the first week of trial for Jayson Van Dyke, the white police officer who shot Laquan, 17, 16 times on Oct. 20, 2014, what remains of my hope for my hometown hung in the balance. And as the jury began deliberations today, justice seemed as elusive as a butterfly in the wind whispering, “Not Guilty.”

These two words cause my stomach to churn over the deeper reality they speak to my soul as a native son in Bigger Thomas’ town: That in Chicago, my beloved city, black lives really don’t matter. And yet, I hope.

That the pretense for state-sanctioned murder of the black male in America remains the same as it has always been — from slavery to Jim Crow to Cointelpro to Rodney King to Trayvon Martin’s America. And even when a police shooting is captured on video and that video shows a story contrary to officers’ reports, the only way for jurors to render anything short of a “guilty” verdict is to ask them essentially not to believe their lying eyes.

“If only they didn’t see us as animals. If only they didn’t believe that the only truly safe black man in America is a dead black man.”

If the jury finds Van Dyke not guilty, the verdict itself will speak to me a glaring truth: That police can shoot me, my brother, my cousins, my sons… That they can mow us down without just cause, like rabid dogs in the street — and get away with it, even if we have no history, no priors with the law.

An acquittal would prove to me that public officials in my hometown — and across America — can seek to suppress the video footage that captures our shooting in cold-blooded horror. That the cops, in a co-conspiratorial blue code of silence, can file complicit reports to corroborate the lie conjured in order to justify their use of deadly force.

That years later, by the time the case finally comes to trial — should it ever — we will be sufficiently vilified by then, our character assassinated, and everything we ever did, every minor run-in with the law fodder for the defense and brought to bear to justify that moment a trigger-happy cop chose to fill us with lead. That the jury of 12 will include only one African American.

That the pundits, usually white, will go on TV, misconstruing and misrepresenting the facts, creating a smoke cloud of mass illusion that could justify even the Crucifixion. And in the end, everyone’s voice would be heard by judge and jury, including, potentially, our killer’s. Everyone’s. Everyone’s, except ours.

Dead men tell no tales.

America’s Foremost Suspect

We are the dead among the living, existing as dark inconsequential shadows in a 21st century, so-called “post-racial America. We are beneficiaries of that prevailing assumption at large in America about the criminality of all black males. I call it the “Justification Equation”:

That as black males we are animalistic, bestial in nature, savage inhabitants. We are America’s foremost suspect, always potentially armed. America’s most dangerous even while brandishing a doctoral degree and dressed in a Brooks Brothers suit. Black males are “bad.” And police are “good.”

So when we are shot, choked to death or otherwise brutalized and deprived of our due process by police, it clearly must have been necessary. The black man must have done something. Our black skin in America assigns to us the burden of proof.

That is how white America sees it — sees us. This is the jaded lens that seldom can be overcome, not even by video footage that refutes police false reports and lies.

That is why whites and blacks can see the same video and decipher diametrically opposed narratives.

“Rodney King kept resisting… That’s why police had to keep beating him. If he had just laid down and stopped squirming…”

“If Eric Garner hadn’t been so big and black and scary, the cops wouldn’t have had to choke him.”

“If Laquan had only followed police orders…”

If only…

If only they didn’t see us as animals. If only they didn’t believe that the only truly safe black man in America is a dead black man.

If only we weren’t sitting ducks in a toxic pond of systemic hate in an America where our duo-curse of race and gender historically have made us the often castrated carnage dangling as strange fruit from poplar trees. The bloated corpses pulled from Southern lakes and rivers. The black souls strung up and burned to a charred crisp in the town square and from bridges while our killers posed and grinned with sunny delight for photographs sent as postcards.

In more modern times, we are riddled with bullets from police firing squads as we sleep. Or police detectives attach electrodes to our genitals to coerce false confessions. Or a police officer shoots us 16 times for brandishing a three-inch pocketknife.

Soul Cries

At age 57, after all this time of living while black in America, my soul is at last tired. It is exhausted of hope, drained by the false pretense of “one nation, indivisible with liberty and justice for all,” amid the hypocrisy of democracy. Even up North in the so-called Promised Land that has become a tarnished land complicit in our oppression, dating back to America’s original sin: Slavery.

My soul cries. It lies this morning upon a bed of pins and needles as the jury weighs testimony it has heard and an impending verdict holds the fate of my city.

Two young black men I encountered within the past two weeks outside the limestone Circuit Court building also expressed a lack of faith in the system. There is no justice to be had at the courthouse, they said. No expectation of fairness and decency upon encounters with police in the street. Not for black men for whom justice is discretionary and elusive. No justice for Laquan. For what justice can he receive when he’s already dead?

“Not guilty.”

The thought infuriates me. Damn the facts. Damn the video that shows Laquan moving in the opposite direction of Van Dyke when he was shot — a fact that contradicts statements by seven police officers who allegedly lied about the shooting, according to police officials, and whom the police superintendent is reportedly seeking to fire.

Damn the fact that within seconds of being one of the last police officers to arrive at the scene that night, Van Dyke, within seconds of exiting his vehicle, emptied his .9 mm service weapon into Laquan’s body from head to nearly foot.

Damn the fact that Van Dyke knew absolutely nothing about Laquan’s troubled personal past when he arrived at the scene. He saw a black boy with a pocketknife. He shot him with perfect aim as his body jerked and smoldered from 16 rounds of heat. That is the image burned into my conscious. And “not guilty” is the anticipated verdict that vexes this native son’s soul.

I would have to be an eternal optimist to believe otherwise. I would have to hope against the fibers of my entire black being that a white cop could be convicted of killing a black boy in Bigger Thomas’ town, where racism and segregation blow in the wind and are baked into the soil. Here, where the existence of two worlds — one white, the other black — causes us to see the facts of this case in starkly different ways.

“Three people killed Laquan. The cop who pulled the trigger and his mother and father,” a reader wrote to me recently. “What was a 17-year-old doing out in the middle of a street with a knife? He was high on drugs. Why wasn’t he home doing homework if it was a school night, or some place under adult supervision if it wasn’t a school night?”

His family “had 17 years to teach Laquan to stay out of harm’s way. They failed. They are just as guilty as the cop who shot him.”

No. They’re not. The only one to blame for Laquan’s murder is Van Dyke…” I wrote back. “There’s plenty of blame to go around for the tragedy of Laquan’s life that brought him to that street that day. But only one man pulled the trigger — 16 shots.”

Period. Case closed.

“Not Guilty.”

Perhaps I am too cynical. Perhaps “justice” will prevail. Perhaps not.

This much I do know: That no matter what the trial’s outcome, it won’t bring Laquan McDonald back. But convicting his killer would preserve one native-born black boy’s hope and prayers for his beloved city’s soul.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com

Website: www.author.johnwfountain.com