'Unforgotten': The Murder and Disappearance of Thousands of Black Women and Girls

Sound the alarm. Let the church call for the mourning women. Until Black lives matter—to us and others, regardless of color or class—let us pray that this city and our nation will regain its lost soul

By John W. Fountain

AFTER ALL THESE YEARS, I am sorely convinced that Black lives still don’t matter—most importantly, not even to us as Black people.

Shush. I know this is not the politically-correct thing to say. That after my opening refrain, Black-ademics, the Afro-stocracy, and those fist-pumping Blacker-than-thou soul brothers and sisters might be ready to cancel me—at least to demand revocation of my Black card.

But before I relinquish it, let them prove to me that what I said isn’t true. Go ahead. Prove it. At least first hear me out...

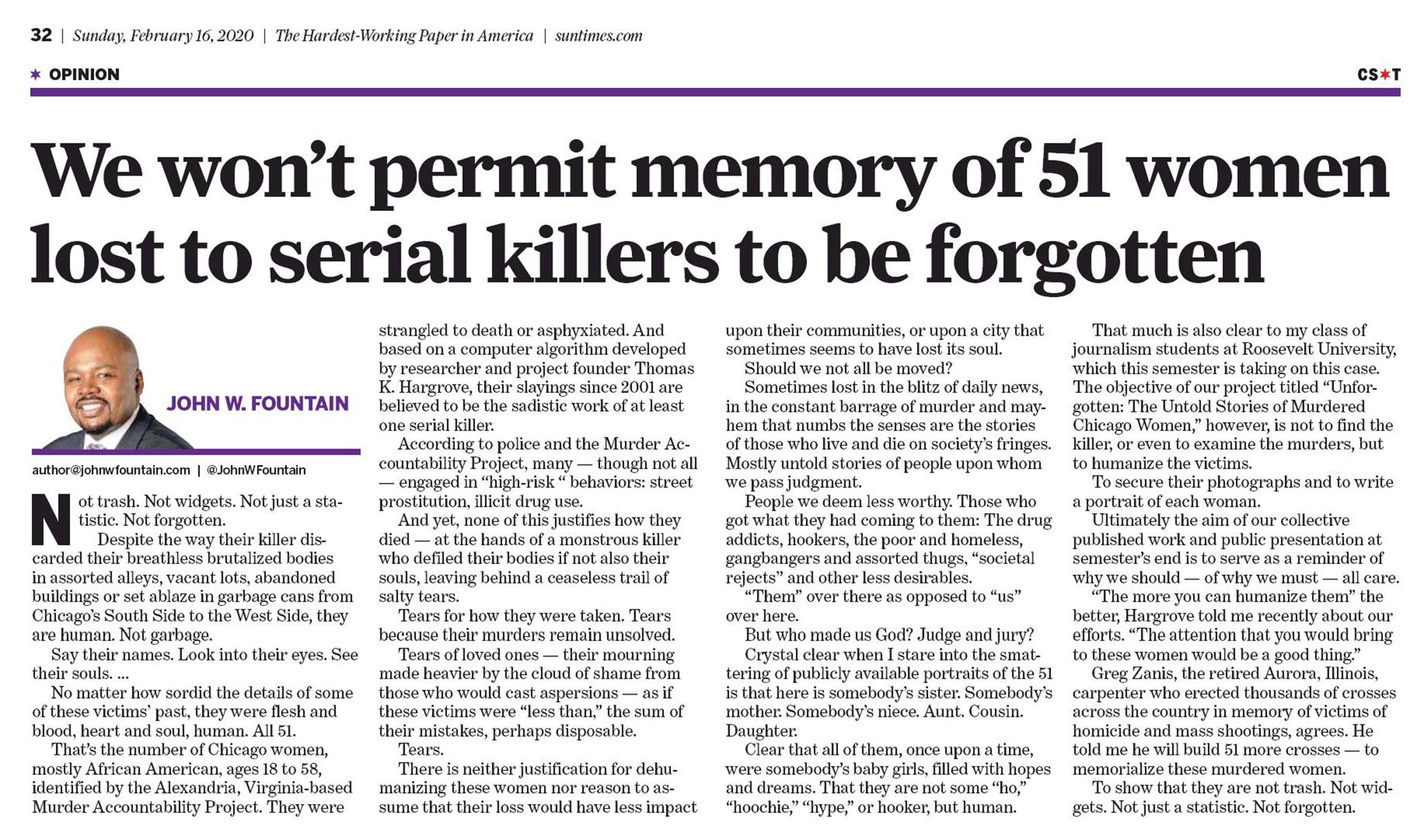

Where is the outrage among us Black folk over the at least 50 mostly African-American women murdered in Chicago since 2001 possibly by at least one serial killer? Where’s the mass outcry among us over the more than 5,000 Black women and girls murdered across America from 2019-2021 alone? Where are the marchers and hell-raisers infuriated over the nearly 98,000 Black females listed as missing in 2022, according to the National Crime Information Center?

Why have I never seen Black Lives Matter protestors wading in a sea of humanity and impassioned, spit-spewing chanting and sign-waving as they march through the ‘hood demanding justice when another young Black man is gunned down by another young Black man? Only when the killer or assaulter is white.

Where is the Black Lives Matter movement after yet another mass shooting by a young Black man with a “chopper” on the block that leaves yet another trail of blood, carnage and tears? Why have we as a race of people been so numbed into complacency and a state of near complete blindness and deafness with regard to the disappearance and murders of thousands of Black women and girls? Why are we so mute?

Why is there no sense of urgency among us, except among those relatively few vigilant activists, town criers, and those loved ones of victims who cry in the wilderness—beg—for the news media, police and anyone sympathetic to their cause to help them seek justice, answers and the return of loved ones still missing, or at least help to humanize them?

I’m not saying that we aren’t as Black folk at all moved by the death and disappearance of Black lives. Only that this crisis summons no urgency, no compelling afterthought that prompts a plan to move forward into action. No townhall meetings. No demonstrations outside city hall, police headquarters, or the nation’s capital.

No piercing collective cry rising from our communities to an undeniable, unignorable crescendo. No sense among our mass compilation of innumerable daily posts on social media— from the ridiculous and obscene, and incessant twerking, to blissful indulgence—that this crisis is burgeoning among us. It is as if we suffer mass selective amnesia, at least have become selective in our outrages, tolerances and causes.

We bury the reports and news of murdered and missing Black bodies in the recesses of our minds, relegate them, consciously or unconsciously, to the back pages of our daily lives, or to our mental archives as hazy news blurbs. Even if our hearts cannot completely avoid grieving for this empirical extinguishing of Black bodies and souls.

We major in minors and minor in majors. Tweet to virality about Keke Palmer’s choice to publicly expose her hinder assets as Usher serenades her to the chagrin of her baby daddy.

What if we tweeted about murdered and missing Black women and girls with the same fervor and consistency, made that go viral?

But Brother Fountain, don't you think you’re being too harsh? I can already hear it. My response:

I am not harsher than the stabbing pain of a grieving mother to a murdered daughter whom she must now bury, or who is still missing, having suddenly vanished from this earth without a trace, like a vapor, (like Diamond and Tionda Bradley). Not harsher than the grave.

Not harsher than this crisis that demands, yearns, for our attention.

‘I Still Believe In Journalism’

I HAVE SAID BEFORE and I will say again: That if this many dogs—or cats—were missing or slain, “we” would be up in arms. If the killers, adductors or assaulters of these Black bodies were thought or known to be white, we would engage in riotous protest, shout, “Burn it down.” And yet, we are not so moved to action.

Indeed the sun rises and sets each day, the seasons come and go, and this collective case of missing and murdered Black women does not grace the daily agenda of Black life or Black urgency in America, nor in our local communities, some of which have become virtual news deserts. Does not rise to the level of critical importance so that the issue is never far from our lips, our prayers, or the pulpits of so-called spirit-filled and led Black churches on Sunday mornings. Neither is there a concerted national effort among us to save us and bring more attention to this issue with the intent to resolve it.

As a veteran journalist, I have waged the battle inside some of America’s most storied newsrooms to write stories about Black deaths and lives. And I have seen white—and Black—editors’ eyes glaze over as I pitched such stories. Still, I persevered in the telling of these stories even when editors told me not to, and even when other reporters expressed little-to-no interest in them, believing that these stories, our stories, are also “news.”

And yet, most disappointing in carrying these stories to fruition—having done the painstaking and emotionally draining reporting, and carrying them against the grain to publication—is the milquetoast to nonreaction of our own people. And yet, I believe that we must stay on the wall. Speak the truth. Shine the light. Continue to sound the alarm through this vehicle called journalism, even as we reimagine journalism in these times.

I still believe in journalism. In its purity, which seeks those who embrace its foundational ideals and principles of truth, fact, and loyalty to readers. In its existence as the Fourth Estate guaranteed by the First Amendment. As defender of democracy, justice and freedom for all, even the least of these.

I and others have risked being pigeonholed by some in an industry that regards Black journalists who want to write stories about Black lives, deaths and issues affecting Black people—even if not exclusively—as one-trick ponies. They regard us as being filled with biases rather than invaluable insight. (Even if, the truth is that we are no less complete journalists able to cover any and every story. Give us oxygen and send us to the moon, and we will find and write the story.)

These same critics never question the ability of white reporters or journalists of other races and ethnicities to cover stories about their own, and, in fact, greenlight their pursuit of stories about the African-American community as they become so-called experts on the Black condition. This despite their own inherent biases as “outsiders looking in,” and arriving in American mainstream newsrooms having grown up in mostly white neighborhoods and attended mostly white schools from kindergarten through college, without a clue of Black life in America.

The stories produced are often jaded, shortsighted, filled with stereotype, inaccurate, and more harmful to the Black community. And our issues ultimately too often are filtered through the lens of white America, which is even more detrimental due to the dearth of news for us by us.

Truth is, I don’t expect white America necessarily to care. But what about Black America?

‘Sounding The Alarm’

I SUSPECT THAT IT is not racial lines that divide us internally but class lines. That the combination of race, class and gender allow many of us to see this as a “them” versus “us” issue, evoking Zora Neale Hurston’s description of Black women as the “mule of the world.”

They are not mules. They are our mothers, grandmothers, sisters, aunts, wives, lovers, daughters. Rich or poor. Greek or non-Greek. Suburban or city. And they are at the center of a mostly silent crisis in America. Still, we remain silent—at least until the issue suddenly seems to hit home, encroach upon our territory, come creeping up our own front doorsteps. A friend couched it this way recently, quoting her dearly departed grandmother: “Nobody cares about the leaves falling until one falls in their backyard.”

I suspect that is why we cared so much about Carlee Russell, allegedly kidnapped after going to the assistance of a young child she spotted on an Alabama highway, when her story broke this summer. Her case pressed all the right buttons: middle-class; a sorority girl versus an “around the way girl”; a nursing student from suburban Hoover, Alabama, where the listed average household income is 122,886, plus the “sensational” circumstances surrounding her disappearance (Thursday July 13). Carlee’s story rang in Black communities across the nation and at the same time drew national attention to the lack of coverage that cases of missing and murdered Black women receive in the news media.

Carlee’s story turned out to be a lie as she returned home 49 hours after her disappearance, later apparently confessing to police that she faked her kidnapping and that her entire story had been fabricated. The temporary media spotlight turned on the cases of missing and murdered Black women quickly faded. And yet, the truth about countless Black women and girls remains.

Truth is: From 2019 through 2021 alone, 5,240 Black women and girls were killed. Their 2,078 homicides recorded in 2021 represented a nearly 54 percent increase since 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The truth?

Homicides of Black females outpaced the number of homicides overall nationwide, which rose comparatively by 36 percent. Black women experience nearly three times the homicide rate of white women. Firearms were used in 53.9 percent of female homicides, although at a higher rate in the homicides of Black women, at 57.7 percent.

The truth is that even as homicides among all persons in the U.S. rose 30 percent in 2020, the rate for Black females exceeded that number, spiking 33 percent, despite accounting for roughly only 7.3 percent of the U.S. population.

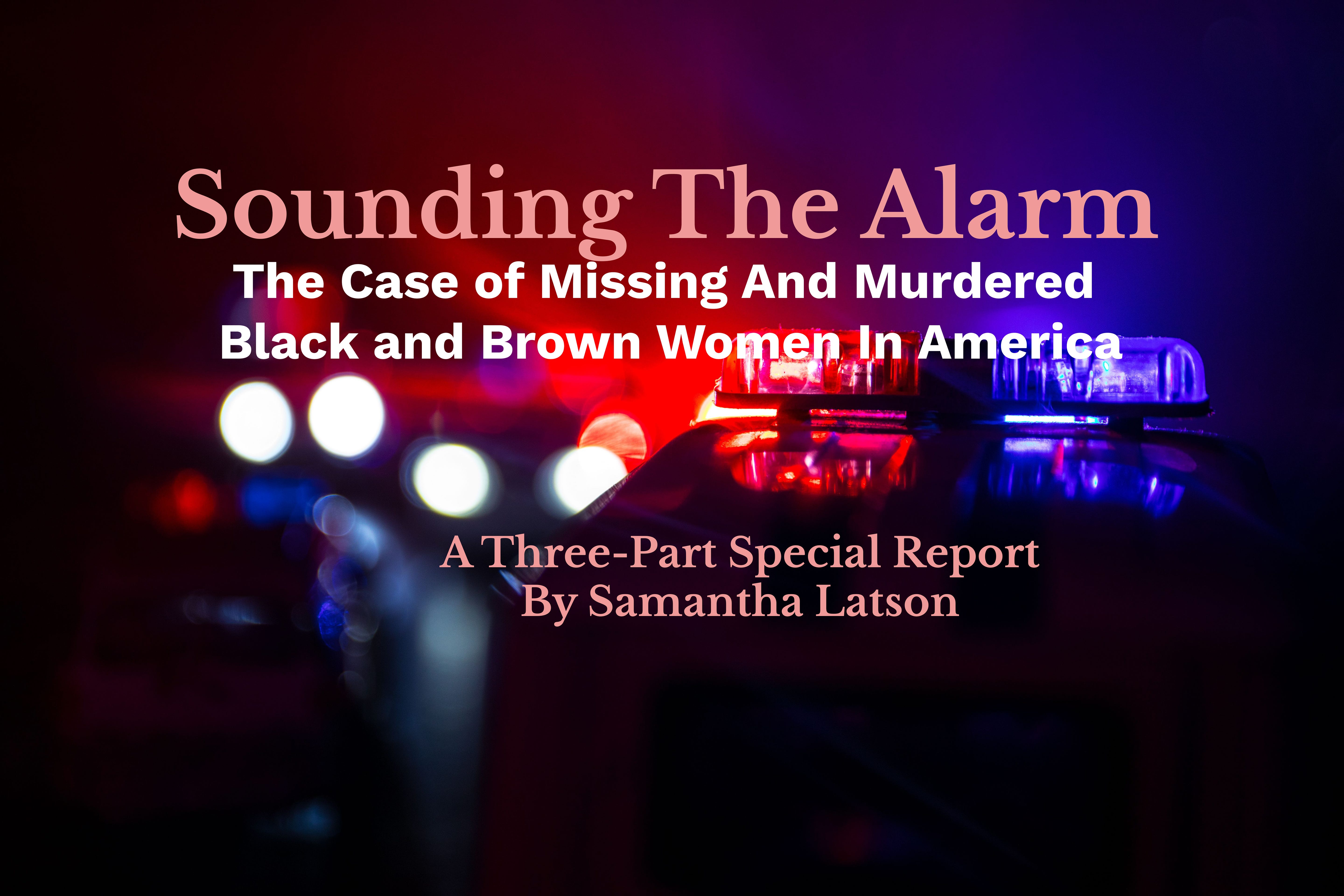

The truth? “That missing Black females and males in 2022, according to the National Crime Information Center, accounted for 35 percent of a total 546,568 missing persons cases despite Blacks comprising only 13.6 percent of the U.S. population. Of that 35 percent, 97,924, or more than 50 percent, were Black females; 95,194 were Black males; and there were 33 missing Black persons for whom gender was unknown,” journalist Samantha Latson recently reported.

All of these numbers and more are detailed in a powerful investigative three-part series by Latson, herself an African-American woman. Titled, “Sounding the Alarm: The Case of Missing and Murdered Black and Brown Women,” it ran recently. Not in the New York Times or the Washington Post, or even in either of her hometown big-city daily newspapers—though in my estimation it is good enough—but in the Chicago Crusader, a historic more than 80-year-old Black newspaper. And yet, I must ask why this story isn’t on the front pages or home page of websites of every Black press organization in America.

That glaring absence does not diminish the value of Latson’s work nor the Crusader’s commitment. Does not reduce her top-notch reporting, powerful writing, or her sensitive and dedicated approach to the subject at hand. Her story is one that is rarely recognized or pursued by the mainstream press. One that historically has been ignored. It is a story—I have become convinced as a journalist with nearly 40 years of experience—that the American mainstream news media have no appetite for, or interest in, despite it being one of the most significant and consequential human issues of our time.

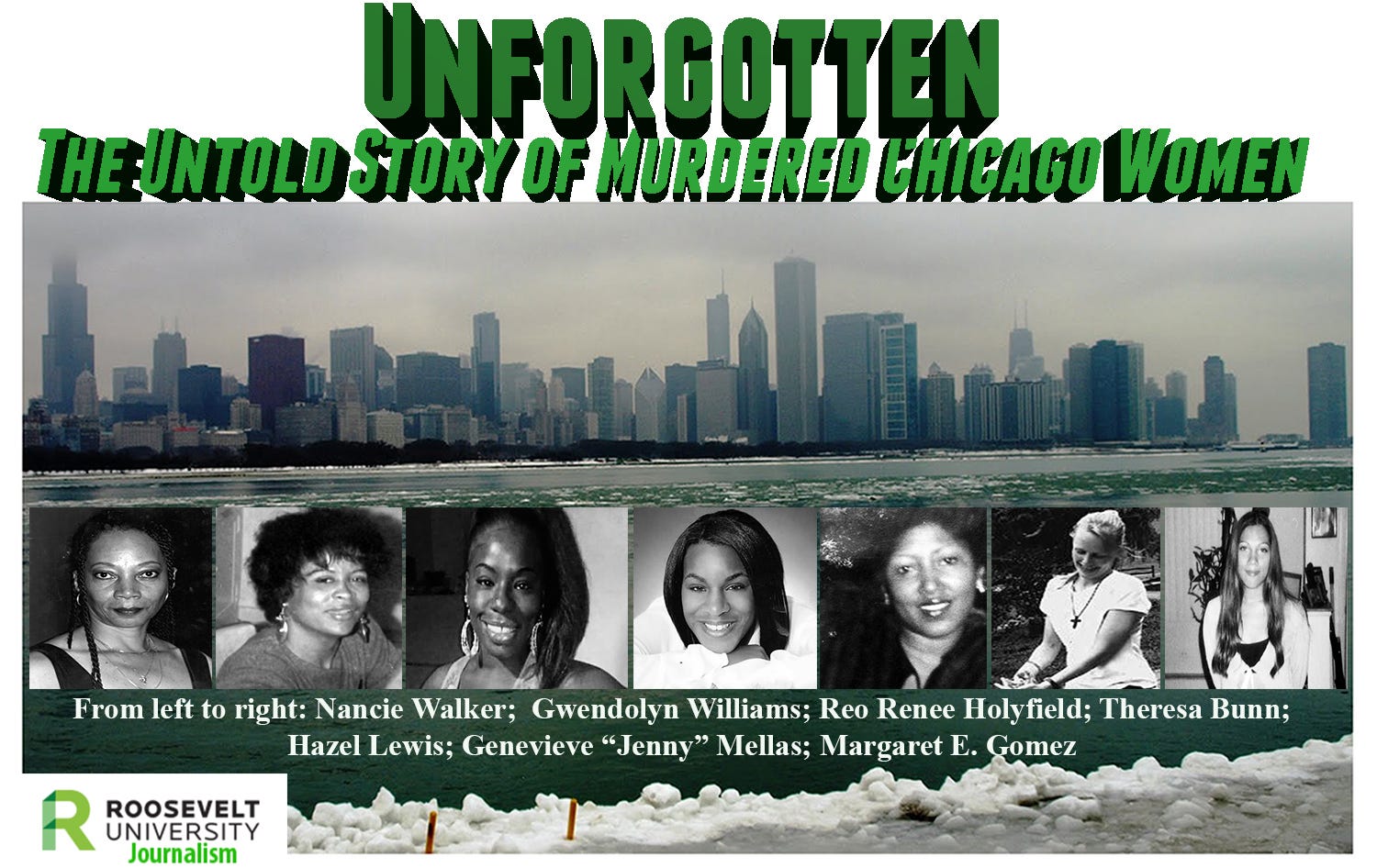

Indeed Latson’s series is an expansion of her work as an undergraduate student at Roosevelt University, where as one of my students then she was a reporter and editor for the Unforgotten 51 project on the 51 murdered Chicago women. “Sounding The Alarm,” which she produced independently as her graduate capstone project at Indiana University where she recently earned her master’s degree, elevates her previous work by examining this issue nationally empirically and also anecdotally. Her effort seeks to humanize the loss inherent in the numbers in a way that summons readers to empathy while also educating them and showing us all why we should care.,

I can’t think of a better vehicle to publish an urgent and critical series like this one written by a Black female journalist than in the Black press. One that in the spirit, audacity, and journalistic craft and passion of Ida B. Wells sounds the alarm.

I only wonder why we aren’t all sounding the alarm. Why it seems that Black lives don’t matter to Black people. And yet, it is not too late.

‘Until Black lives matter to us all’

SOUND THE ALARM. LET it begin with the church. Let the church call for the mourning women. And until Black lives matter—to us and to others, regardless of color or class—let us pray. Pray that this city and our nation will regain its lost soul. Pray that Black and brown neighborhoods will be made whole.

Pray that we will cease to be so cold-blooded. Our bloodstained cities now flooded with steel rain. With mothers’ pain. With rivers of murder and endless names, lives and souls claimed.

Pray. For divine intervention amid impotent good intentions by the powers that be. Amid the church’s laxity. Amid the abandonment of morality by too many in our community.

Pray against the disintegration of family. Against the infestation of depravity that has eaten at the fabric of our cities like cancer. Pray. For vengeance, retaliation or federal troops are not the answer.

Pray for the solution, for resolve, for unwavering will. Pray that peace will be still and confiscate this chaos. Pray that light will swallow up this darkness that fills the hearts and minds of too many young Black men with the insatiable lust to kill and kill again. Pray that those responsible for slaying and snatching our women and girls from this world would be unveiled and brought to justice. Pray.

For righteousness exalts a nation, not sin, hate or murder.

Pray that God will transform the hearts of men. However grand the plan to mend our ailing soulless cities, let it begin with prayer.

With the faithful fervent prayers uttered by our ancestors whose spirits still yearn for peace, freedom and the posterity of Black people. Prayers that lifted us up from chattel slavery to build grand institutions, even churches with grand steeples.

Prayers that preserved us from cruel slave masters’ hands. Prayers that led us as we walked through the valley of the shadow of death across America’s lynching land. Across the desert sands of Jim Crow’s hate-filled plan. The prayers that helped Martin, Malcolm, Medgar and John Lewis stand.

Pray. like we used to—before complacency set in. Before we began to mimic the oppressor’s plan. Before the glint of materialism stole our spiritual affections like a grand ploy that left us wandering across this Promised Land.

May we pray. And may we sound the alarm. Until Black lives matter to us all.

Email: author@johnwfountain.com

#JusticeforJelaniDay