'Under Attack, We Must Fight Back'; Reimagining Journalism, Reviving My Soul

Whatever betides, we must stand as journalists and journalism educators 10 toes down against those who seek to co-opt journalism, against naysayers and denouncers.

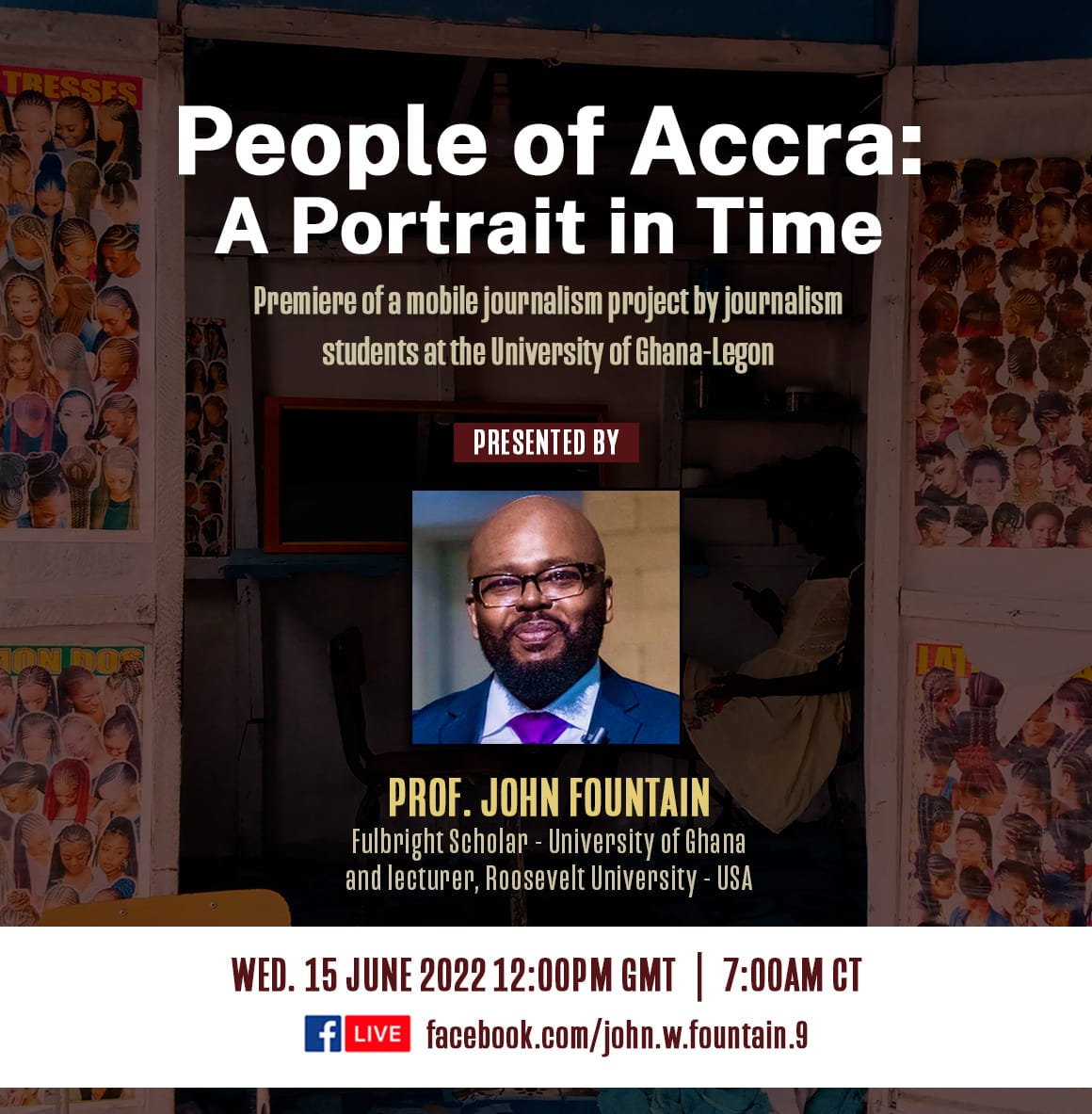

By John W. Fountain

CHICAGO, Jan. 17—STANDING TODAY IN FRONT of my first class for the spring semester at Roosevelt University in this my 16th year, I clutched a pocket copy of the U.S. Constitution I discovered in a pile of books on a windowsill in the back of the third-floor multimedia lab.

The brief discussion was not part of my prepared lesson plan. But flipping through the pages and examining the Constitutional amendments, I could not help but reflect aloud on the critical importance of the historical document to American life, democracy and a free press.

“How many of you could pass the Constitution test if you took it right now?” I asked half-jokingly, although inside ruminating on the ensuing attack on democracy and the fragility of our republic, notwithstanding the continuous assault on the free press.

At least one student said they could pass the U.S. Constitution test, which they had last taken, at best recollection, sometime in elementary school. I joked again that I could probably pass with at least a grade of C.

Whether American journalism as an institution and also its practitioners can pass the test currently confronting us, however, is a different, even if related, matter. Indeed journalism appears to be under attack both from inside newsrooms themselves and also in academia, the epicenter of training for future journalists.

The more daunting question emerging from the flames and smoke emanating from an institution and industry on fire is: Can or will journalism survive?

Premature Autopsy

AS A NEARLY 40-YEAR newspaper man and 20 years as a journalism professor, I think that any autopsy on journalism would be significantly premature.

Admittedly, however, it seems that gone are the glory days of journalism when the news media—operating as the Fourth Estate, as public defender and gatekeeper—made many a would-be young reporter dream of jumping into the journalism fray. It was a time when so many of us in J-school aspired to someday do the work of Woodward and Bernstein. To become investigative big-city reporters.

We dreamed of covering wars in foreign countries, or traversing the nation as a correspondent. Of chronicling the stories of life in middle and small-town America as the eyes and ears of readers. Of capturing slices of life, unearthing human tragedies and injustice, and serving as gatekeepers between the government and the people, upholding the public’s right to know. Of doing the kind of journalism worthy of a Pulitzer Prize.

In these times, however, it appears that neither journalists nor journalism are safe. It is a point that glares like the glint of sun off chrome as I ingest news that at least 83 journalists and media workers have been killed so far in Israel’s bombardment in the War in Gaza, and which, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, “has led to the deadliest period for journalists since CPJ began gathering data in 1992.”

If journalism’s glory has waned, however, it is not likely due to some natural cyclical decline in interest or to any truth to the predictions of journalism’s impending demise. As I see it, the loss of journalism’s luster is the byproduct of an assault on several fronts and an increased palpable disdain for the institution itself and for journalists.

The assault against a free and independent press over at least the past eight years has come in waves of cries of “fake news” spurred in part by former U.S. President Donald J. Trump who told the American public that journalists and news organizations could not be relied upon for truth. That we should instead believe only what a man with a well-documented propensity for lying and for skewing facts and truth says. The same man who in 2015 during a campaign rally mocked a reporter with a disability.

The disconcerting reality that the world of journalism is in turmoil is evidenced by a deluge of reports of financial trouble, buyouts, layoffs and cutbacks at major newspapers (the Washington Post, more recently the Los Angeles Times, and apparent brewing troubles at the Baltimore Sun.) In fact, 42 of the 100 largest U.S. newspapers no longer print daily, according to a report published by the Poynter Institute. The latest punch in the gut for print journalism is the announcement this week that Sports Illustrated is laying off most of, if not its entire staff.

That the newspaper industry continues to shrink amid the loss of advertising and subscription revenues, the inability of many newspapers to effectively monetize digital content, and the aging out of a generation that grew up inhaling and holding newsprint between our fingers isn’t a new story. The hemorrhaging, according to observers and analysts, is due less to an attack on the press and more to the impact of technology and the changing and emerging habits of news by consumers in a digital age.

As Jack Shafer, senior media writer at Politico, put it, “Yes, newspapers have contracted and laid off staff. Yes, more than a quarter of all U.S. newspapers (daily and weekly) have folded over the past 15 years. Yes, newspaper advertising revenue dropped 25 percent from 2019 to 2020. Yes, 42 of the 100 largest U.S. newspapers no longer publish daily. …Yet, the heart still beats. The Post will still have a newsroom of 940, which is 360 more journalists than the paper employed about a decade ago.”

So newspapers—and journalism—aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. But there are other, perhaps more pervasive, forces at work.

The Way of Dinosaurs

AT THE HEART OF it is the erosion of public trust outside newsrooms. It is the editorial push inside newsrooms for clicks and for reporters to produce frivolity rather than substantive journalism that matters. It is the distaste expressed by management at some newspapers for stories about homelessness, about poverty and injustice, about racism and discrimination and stories of the powerless, the underclass, the voices and faces of those who dwell far beyond the American Mainstream, but instead in the American Drained Stream “because our readers don’t want to read those kinds of stories because it makes them feel uncomfortable.”

At the heart of the matter is the merging, dismantling, and/or watering down of journalism education in the name of broader sexier “media studies” or “multimedia” course titles and curricula with the aim of boosting enrollments and with little regard for guarding or promoting or preserving the craft, practice, or teaching of journalism. But AI shall not inherit the earth. It has neither heart nor soul. …And the acquisition of techy, social media or multimedia tools is comparatively unessential to those skills requisite for producing good journalism. I know because as a classic print journalist I am as comfortable editing video and audio or taking photographs and designing multimedia and websites as I am writing an inverted pyramid style lead. But I digress…

At the heart of the matter is the apparent unwillingness, or at least absence, of a respectable concerted effort in defense of itself mounted by journalists or by the news industry at large. The absence of a collective effort to fight back. The resolve to stand on principles and in purpose, and to esteem the virtues and critical importance of journalism to a democracy. To sound the alarm about the potential fatality of democracy if a free and independent press should someday meet its demise.

But how do you fight back when suddenly you lose your job? The short answer: Reimagine Journalism.

That print newspapers are likely to go the way of dinosaurs—even if the final epitaph has yet to be written—is a foregone conclusion. But the public’s right to know and our reliance upon independent journalism will demand journalistic practitioners classically trained to pursue the five W’s and the H as third-person objective observers. They will remain essential to journalism’s survival in whatever mutation of an aggregated news product arrives at the digital doorstep of consumers in the future.

It is, therefore, essential that those journalists of the future also be well-versed in the Elements of Journalism and wed to its core principles. Among these: That journalism’s first obligation is to the truth; that its first loyalty is to the reader or the citizens; and that journalism is a discipline of the verification of facts. Future journalists will still need to study the art and craft of interviewing, reporting, and mining a news beat and cultivating sources.

They will need to master the various forms of journalistic storytelling, to be knowledgeable of journalistic ethics and issues, and of the history of journalism and its indispensable role in social justice movements in America and beyond.

So colleges and universities worth their salt must neither abandon nor forsake journalism programs, even amid burgeoning budgetary concerns and declining enrollment in which it is easy to scurry to the safety and security of other departments and programs not yet affected. But what you gon’ do when they come for you?

Furthermore, what does it say about any university or college that does not seek to preserve and protect journalism, the vanguard for truth, freedom, justice and equality—its soul? It is a question I must ask of my own university named in honor of Franklin D. Roosevelt and whose wife Eleanor Roosevelt was a founding member of the advisory board and herself a journalist.

‘Revives My Soul’

WHATEVER BETIDES, WE MUST stand as journalists and journalism educators 10 toes down against those who seek to co-opt journalism, against the naysayers and denouncers. Against the thieves and appropriators who would now assert some intoxicating semblance of journalism or seek to pass themselves off as the real deal. They’re not. We are.

So we must stand. Despite the disrespect in an age of posers on prime-time so-called news shows that are little more than infotainment with talking heads, or else filled with mediocre celebrity journalists driven more by self-promotion and fame than by the story. Despite even the cheapening of newspaper column writing. One of my hometown daily newspapers here (which coincidentally paid me 50 cent a word for 13 years before I quit for a number of reasons) has turned to soliciting guest columns under the guise of an opportunity to hear from “the community,” but which serves as cheap filler by amateurs, not professional journalists. (Honestly, it just makes me sick.)

And yet, I am sick and tired of being sick and tired. The question for us as journalists is: What are we going to do about it?

We must reimagine journalism and consider independent news entrepreneurship, seeking to become the change we want to see. We must teach and reassure those who follow that where journalism goes from here is truly in our own hands. And we must stand. Amid the latest news of cutbacks and layoffs, of uncertainty, we must stand.

Honestly, it’s enough to make an old newspaperman and journalism professor like myself shudder. But this I know: The difference between journalism and its impersonation is as glaring as the divide between fact and fiction. There is no thin line. And the preservation of journalism, like the preservation of our democracy, is worth the fight.

That is as clear as the pages of U.S. Constitution booklet that ran smooth between my fingers and whose words about the press in the First Amendment revive my journalistic soul.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com

We Do Journalism

English, Sociology, History, Philosophy. They all have their place. But we do Journalism.

Real people, real issues, real lives, real stories. In the real world.

Human stories told through the journalistic craft of reporting and writing. Girded by the foundational principles, ethics and practice called Journalism.

Facts, Truth, Justice, Democracy, Accuracy and Fair Play. All are at the heart of journalism: “A current, reasoned reflection, in print or telecommunications to members of a society, of society’s events, values and needs.”

Journalism. The stories of everyday life. The first draft of history. Stories that matter.

Like the story of what happens “When The City Turns Cold,” as reporters take readers to the front lines of the house-less in Chicago who, when winter comes, face subzero temperatures in the city’s frozen streets to shelters that work to provide refuge, and to other places where people are fighting to make a difference.

Like the story of The Faith Community of St. Sabina and their 12-hour bus trek to the nation’s capital for “The March To End Gun Violence”—with student-journalists embedded to chronicle the story—from start to finish. Providing a timestamp of daily events that matter.

Like “Saving Our Sons”—an intimate journalism story about the effort in Chicago to address the toll of murder against young Black men by young Black men. The underlying social complexities and the heart-wrenching stories of grieving mothers.

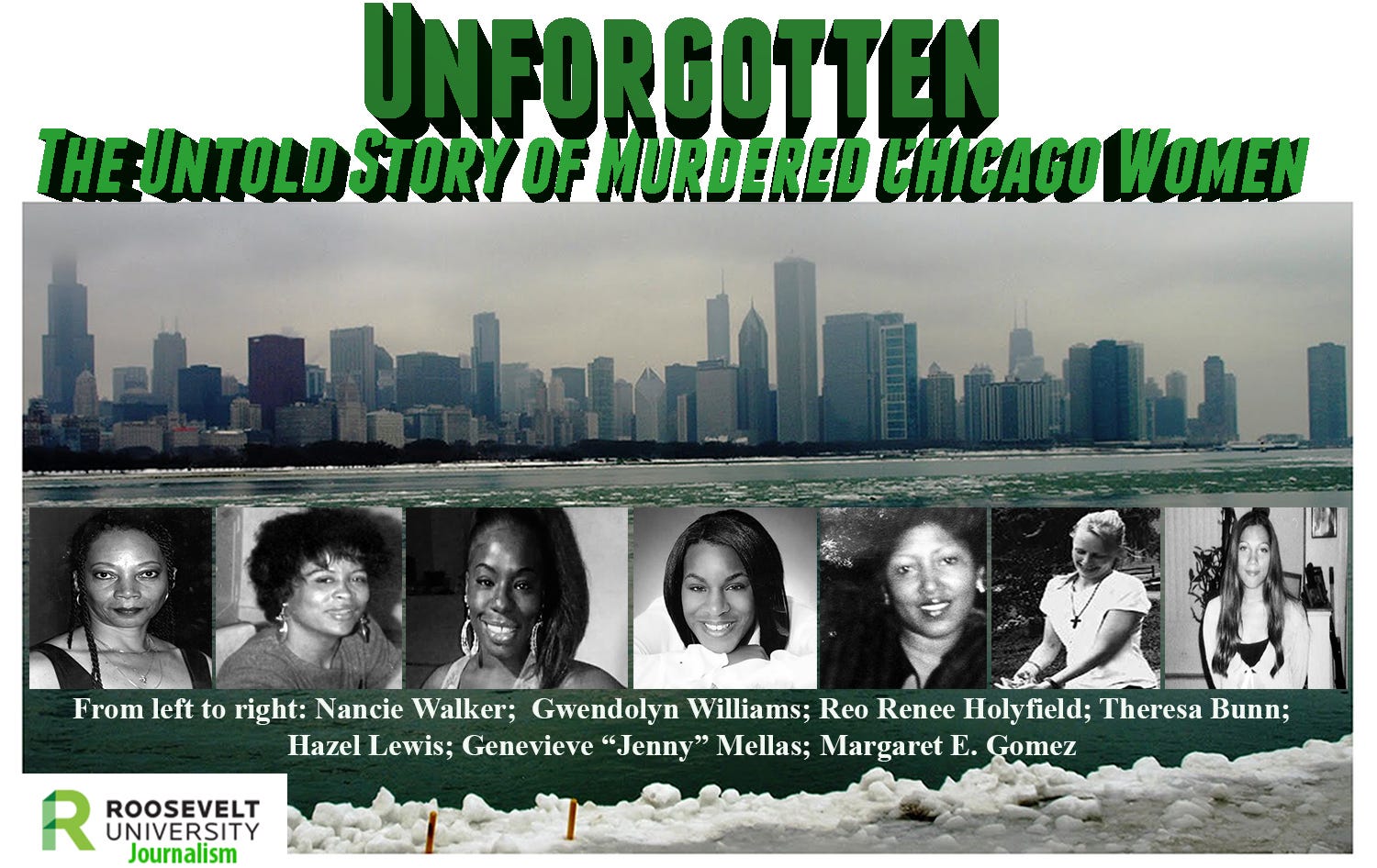

Like “The Unforgotten”—the untold story of 51 mostly African-American women in Chicago murdered by possibly at least one serial killer. Student journalists taking on the case to tell these women’s stories. To humanize them.

Journalism. True stories told in real time. Stories about life. And death. Portraits from the Mainstream and the Drained Stream.

Stories about poverty. Triumph. Hope. Love. Loss. Tragedy.

Stories that afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.

Non-fiction storytelling produced by agents of the Fourth Estate. Torchbearersof the First Amendment right to a Free Press that is indispensable to Freedom and

-John W. Fountain