April ’68: When A Neighborhood Died

This column is an excerpt from my memoir, True Vine: A Young Black Man’s Journey of Faith, Hope and Clarity, about my childhood…

This column is an excerpt from my memoir, True Vine: A Young Black Man’s Journey of Faith, Hope and Clarity, about my childhood recollections of the aftermath of the Rev. Martin Luther King’s assassination.

By John W. Fountain

I stood barefoot at age 7, watching the fires from my apartment window. The angry flames licked the pale night sky above the West Side of Chicago. There was an unusual rumbling out on the street, mixed with the voices of unrest, the slapping sometimes heavy thud of hurried feet beneath our third-floor apartment window on 16th Street and Komensky Avenue in the neighborhood we knew as K-Town. I could not see their faces. They could not see mine. We were all in the dark.

From the night came the crashing of glass, the blare of sirens. The screams of human anguish. A symphony of chaos.

The smoke seeped into our living room. It settled over the varnished hardwood floor like fine dust and carried the scent of charred mortar and brick. Mostly ablaze were the Jewish-owned clothing stores and businesses along Pulaski Road.

The fire that April night ran up and down Pulaski even as far north as Madison. The fire I witnessed from my window was from hell. That much I could sense even as a child as I watched the embers spit into the sky.

At Pulaski and Roosevelt Roads stood a hamburger joint called Holland’s. A neighborhood landmark back then, the restaurant, with its blue and white windmill marquee that could be seen for miles, would be one of the few businesses to survive the flames.

Earlier that day, I saw all the white folks running from Kuppenheimer, the blocklong brick building on 18th Street and Karlov Avenue that made men’s clothing. Kuppenheimer was where Grandmother worked as a seamstress and where Grandpa and my Uncle Gene sometimes moonlighted as security guards.

By afternoon that Friday, enraged packs of black teenage boys were beating up white people who worked in the neighborhood. I have never known the names of either the victims or the perpetrators. But three decades later, I can still see their faces. Few words are exchanged. Mostly punches for pain.

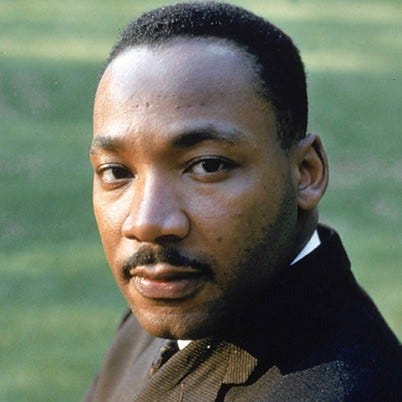

I had heard enough at school and from Mama the evening before to know that the older guys and just about everyone in the neighborhood were mad about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. being killed. The word we kids had learned in school was “assassination.”

It had an unsettling ring, like crucifixion.

“Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated” was the way the news was synthesized and transmitted throughout the neighborhood.

Assassination. It was a big word, a strange word. I’m not sure that I fully understood back then what it meant. I only knew that Dr. King, the man who once lived in our neighborhood just a few blocks away from Komensky, the preacher whose name was on everybody’s lips and the object of everybody’s tears, was dead. But after the night of fires, the same might have been said of our neighborhood.

As I walked to the store the next morning, the National Guard troops I saw riding atop their jeeps up and down Pulaski Road — wearing their green fatigues and assault rifles as the remains of buildings smoldered in smoke and ash — were forever seared into my mind. Years later, I realized that the fires signaled the beginning of the end.

Nearly 50 years later, the neighborhood’s scars are still visible and Dr. King is now long gone. But as far as I can see, there is still, clearly, plenty need to carry his dream on.

Email: Author@Johnwfountain.com

Website: Http://www.johnwfountain.com