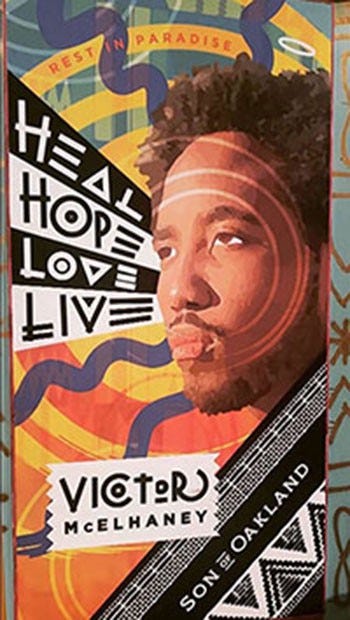

Say His Name

Victor McElhaney, 21, a student at the University of Southern California, where he was studying jazz percussion, was fatally shot in Los…

Victor McElhaney, 21, a student at the University of Southern California, where he was studying jazz percussion, was fatally shot in Los Angeles on March 10, according to police, during a robbery outside a liquor store near campus. From 1976 to 2017, the tally of African Americans murdered across the U.S.: 343,780 — more than three times the Wolverines’ Michigan Stadium, the nation’s largest. Victor was all our son. A murdered American son in a mounting national toll. Writes John Fountain: “If this many dogs or cats had been slaughtered, America would declare a national state of emergency.”

By John W. Fountain

VICTOR MCELHANEY. SAY HIS NAME… We should all know his name. Say his name: Victor McElhaney… He was not a statistic. Not just another headline soon to be discarded from memory amid the so-called breaking news on the morning after. Not just another young black male slain. Not a nameless, faceless murdered brother claimed by the homicidal swell that leaves far too many black mothers to wail in an endless sea of the blood and tears of murdered black men that flows from coast to coast, from sea to shining sea.

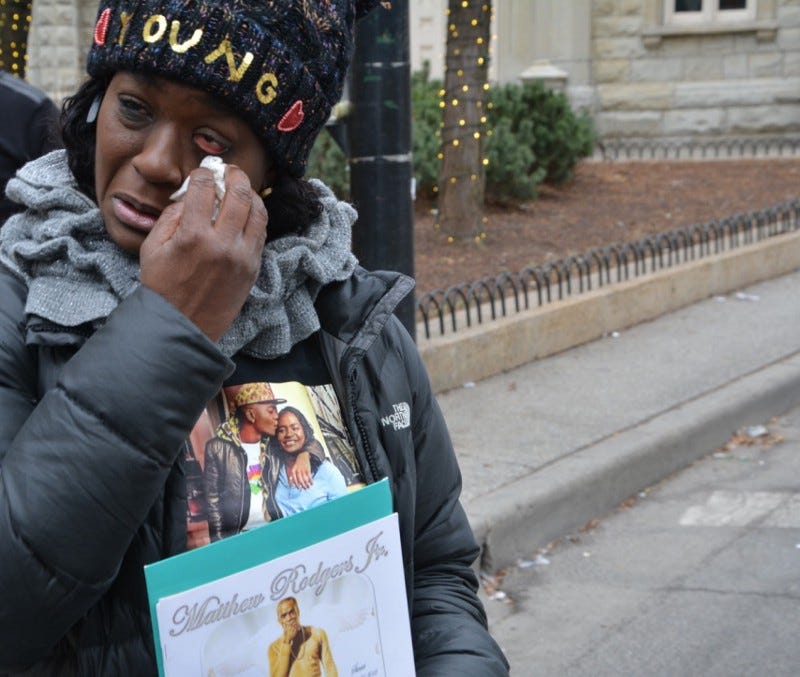

Say his name: Victor McElhaney… He was not a son of Chicago but a son of Oakland, California. And yet, we should all know his name. Victor, 21, was fatally shot in Los Angeles on March 10, during a robbery outside a liquor store near the campus of the University of Southern California, where he was studying jazz percussion. His mother, Lynette Gibson McElhaney, an Oakland city councilwoman, is a longtime outspoken activist against violence.

From 1976 to 2017, the tally of African Americans murdered across the U.S.: 343,780. Nearly four times the 90,000-capacity of London’s Wembley Stadium

It was during a visit a few years ago to my friend Pastor Zachary E. Carey’s True Vine Ministries, where the McElhaney’s are members, and where Victor grew up playing drums, that I witnessed firsthand their fervor and fight. I stood with the church on the city’s streets where they have marched each Saturday for years to bring attention to the scourge called murder.

And yet, here we are. No clear and easy solutions. No end in sight. Only a trail of blood and tears, and senseless slayings that steal even sons of promise by an evil that is no respecter of persons and that runs rampant, particularly in black communities. Chicago — my hometown, where once upon a time I was the Chicago Tribune’s chief crime reporter — stands as a microcosm of our collective seismic sorrow.

“America doesn’t have a murder problem. America — black and white America — has a heart problem.”

We lift our eyes to the hills as they run with a river of salty tears. From whence cometh our help?

It will not come from politicians and assorted poverty pimps whose allegiance is to the powers that be. It will not come from the church, which has lost her prophetic zeal, her voice and purpose. A mostly impotent church that sits fat and mum each Sunday about this catastrophe from which none of Black America is immune. A church that pushes prosperity doctrine, faith conferences and annual church convocations and congresses while the corpses of our sons — and daughters — lie in the streets.

A church that builds multi-million-dollar so-called worship centers topped with grand glowing crosses and sky-piercing spires while it largely has placed on the backburner the building up of temples of flesh and blood and heart and soul. A church that too often ignores the creation of “community,” healing, peace, love and hope and wholeness in neighborhoods they occupy and where gunfire, murder and mayhem reign. A church that has forgotten her first love though a faithful remnant cries in the wilderness — working, praying, fighting, still hoping for change to come.

From whence cometh our help?

Our help will not be from some coming Messiah (Barack Obama did not save us), or by prayer alone. Not by sitting on our hands.

And yet, I pray: Lord, hear our cry…

A PORTRAIT OF MURDER BY THE NUMBERS

The numbers paint an alarming picture Imagine Soldier Field, home of the NFL’s Chicago Bears, filled beyond capacity, brimming with 63,879 young African-American men, ages 18 to 24 — more than U.S. losses in the entire Vietnam conflict.

Imagine the University of Michigan’s football stadium — the nation’s largest — filled to its limit of 109,901 with black men, age 25 and older. Now add 28,223 more — together totaling more than U.S. deaths in World War I.

Picture two UIC Pavilions, home to the University of Illinois-Chicago Flames, packed with12,658 Trayvon Martins — black boys, ages 14 to 17 —more than twice the number of U.S. lives lost in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Now picture all of them dead. The national tally of black males 14 and older murdered in America over a 30-year period from 1976 through 2005, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics: 214,661.

From 1976 to 2017, the tally of African Americans murdered across the U.S.: 343,780. Nearly four times the 90,000-capacity of London’s Wembley Stadium, with 83 percent or 285,164 of them black males compared to 58,616 black women.

“If this many dogs or cats had been slaughtered, America would declare a national state of emergency.”

Indeed in 2017, a mounting body count of African Americans nationwide gave some cities the designation of being among America’s most murderous. The blood of our sons and daughters cries from their graves — from St. Louis to Baltimore to Cleveland and Detroit; from Washington, D.C to St. Louis and Memphis to Jackson, Mississippi; from Indianapolis and back down to New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana; from Oakland, California, back to Milwaukee and Chicago.

Clear too is that killers of black people increasingly are getting away with murder, based on a report released in February by the Murder Accountability Project, a Washington, D.C. based nonprofit research group. The report found that even as the homicide clearance rate for other races rose slightly from 1976 to 2017, it declined significantly for blacks.

“Declining homicide clearance rates for African-American victims accounted for all of the nation’s alarming decline in law enforcement’s ability to clear murders through the arrest of criminal offenders,” researchers concluded.

Moreover, the clearance rate of all black homicides nationally fell from 79.7 percent in 1976 to 59.8 percent in 2017, meaning that 4 out of 10 homicides of black victims went unsolved — about two times the rate for whites. Victor McElhaney’s parents continue to seek the public’s help in identifying his killers.

The numbers raise an obvious question: Why the spike in the number of unsolved black murders, even in rural black communities? The Murder Accountability Project concluded that the “disparity probably has many causes, including perhaps a generalized eroding of relationships between law enforcement and the black communities they serve,” and urged further study into this alarming trend.

That disparity glares in Chicago like the sun on polished chrome. From 1965–2017, of 35,246 homicides reported, only 12,039, or 34.06 percent, were solved, according to the Murder Accountability Project. In January 2018, the Chicago Tribune reported that over a 60-year period — from 1957 to 2017 — Chicago recorded 39,000 homicides. That’s twice the capacity of the Golden State Warriors’ Oracle arena. Dead.

Compared to rates for adolescents in the United States and Chicago as a whole, Chicago’s black male adolescents, ages 15 to 19, in 2017 were at significantly higher risk for firearm homicide and nearly 35 times the national rate, according to report published in March by the Chicago-based Stanley Manne Children’s Research Institute. That is 25 percent improvement from 2016 when the rate for black male adolescents was nearly 50 times the national rate but still alarming.

According to the report, there were 156.7 homicides per 100,000 adolescent black males in Chicago in 2013. That number rose to a rate of 365.3 over a four-year period in 2016 but fell in 2017 to 273.1 per 100,000. Despite the decrease, that rate still represents a dramatic 74 percent rise in firearm homicide among adolescent black males from 2013.

As a former crime reporter who has written about homicide and violence for almost three decades now and as a Chicago native black son, what I find even more disturbing are the number of shootings each year, which have become as routine as the rising and setting of the sun and far surpass the number of those murdered, leaving a trail of survivors maimed, blinded, disabled, saddled with colostomy bags for life, confined to wheelchairs, walking around with bullet fragments too close to vital organs to surgically remove, and with loved ones having to refit their houses with accessibility ramps. The number of shootings, according to police and published reports, for instance, from 2013 to 2017 alone: 15,628 — more than the capacity of the University of Illinois’ Fighting Illini’s State Farm Center.

The gunfire and murder continue. A newspaper headline on June 3 read: “52 shot — 8 fatally — in Chicago’s most violent weekend this year”

Another headline this week announced: “2 Killed, 9 Wounded In Tuesday Shootings In Chicago”

The numbers tell only part of the story of this largely urban war, where the victims bare an uncanny resemblance to their killers. The Spirit of Cain, I call it. A war of brother against brother — fratricide. A war of terror imposed by hooded masked gunmen, not cloaked in white hoods. Not the Ku Klux Klan but black boys and men.

The murder that engulfs our neighborhoods is a dark tale filled with tree-lined streets where automatic gunfire cracks, even in the light of day, as little boys make mud pies, schoolgirls jump rope. Where the innocent are caught in the crossfire, and where the spirit of murder blows steady, like the wind. Or near college campuses where sons and daughters who have escaped or eluded violence back home are cut down.

Say his name: Victor McElhaney. He was flesh and blood, and heart and soul. He was America’s son. Say his name.

But what good will that do?

TAKING AIM AT RESPONSIBILITY

I have heard the critics. “Black genocide will diminish and ultimately cease when blacks realize they must adopt the road to success that every other tribe (race, religion, country of origin, ethnic group, etc.) that have come here did. The road is education, job, marriage…”

To that, I ask: Which other group of people arrived at America’s shores in chains as slaves? How do you discount the impact of 250 years of slavery, of Jim Crowism — by law or government policies — of institutionalized racism against people with black skin? And how do we as African Americans collectively achieve equality in a nation where even innocent unarmed black men are brutalized and shot down by police in what amounts to state-sanctioned murder while armed white men who have committed mass shootings get taken alive?

What is the affect of living in a hypocritical nation where glaring injustices — from separate and unequal public schools to economic and environmental racism — create a river of hopelessness and poverty that now flood hyper-segregated African–American neighborhoods? Neighborhoods that were infused and saturated with crack cocaine and guns and from which mass incarceration and unfair sentencing carried a nation of black men away, fueling a prison economy in mostly white towns. Even as jobs and municipal resources were siphoned from our neighborhoods and we were told to pull ourselves up by our own bootstraps. Except we never had boots.

And yet, we still must rise.

“They wouldn’t shoot if they had jobs,” some say.

“It’s the system.”

“It’s racism.”

“It’s a conspiracy.”

“It’s ‘the man’.”

All may have their effect in helping to create this homicidal plague we now face. Except it is not the white man but largely young black men who shoot little girls and boys — and men and women — dead. Not white men in black face, or else wearing some Hollywood-type mask or body suit to masquerade as gun-toting black men, despite rising urban conspiracy myths. That sounds sexy. But it’s much simpler than that. And most black folk know it.

Black males are the gunmen who spring from shadowy gangways, or stand over a pregnant mother and pumps her with bullets as she pleads for her life — making her unborn son a victim of crime before taking his first breath, or who lure a 9-year-year-old from a park to an alley in Chicago to execute him because of his father’s gang ties.

As it has been said, “No one can save us from us but us.”

Say his name: Victor McElhaney…

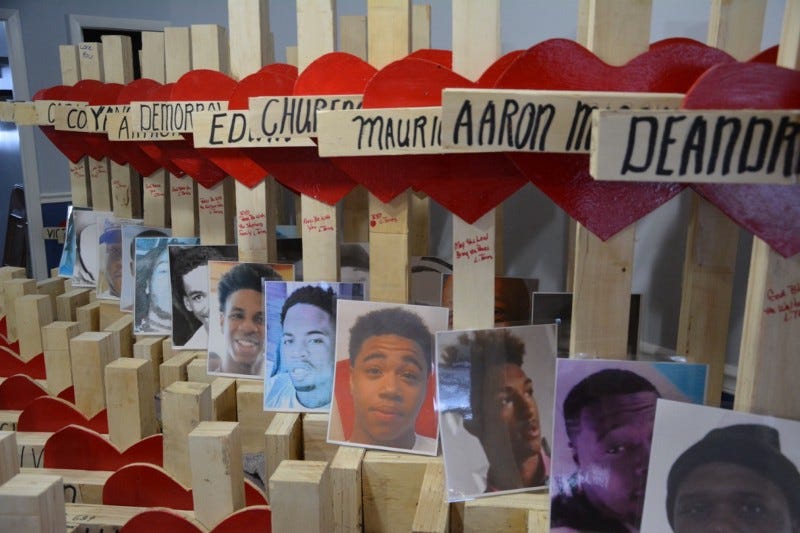

PREMATURE AUTOPSIES

Perhaps speaking Victor’s and the names of other slain sons and daughters will ensure that their names live on, upon the winds of time, which may spread the seeds from which a new generation may grow. Perhaps it will help keep their memory alive in our hearts and minds and also remind those who knew and loved them that they did not live or die in vain.

Perhaps saying Victor’s name, and hearing her son’s name spilling from the lips of others, will help soothe a mother’s grieving heart. Or maybe saying Victor’s name — and the name of other murdered sons and daughters — will help convey to the world the great sense of human loss at a time in America when black lives still don’t matter. Perhaps saying their names will matter because words matter and they can lay the foundation for seismic shifts in a culture’s paradigm.

Victor doesn’t have to be from Chicago for me to get that “we” have lost this son. I don’t have to live in Washington, D.C., or St. Louis, Baltimore or New Orleans to understand that we are all in this together. That “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

America doesn’t have a murder problem. America — black and white America — has a heart problem. A heart whose arteries are diseased and calcified with disregard, dispassion and cold callousness when it comes to black lives. Black lives don’t matter in America. But they must first matter to us black folks. And I can’t say that they do — at least not to enough of us. Let a white cop shoot one young black man and we are ready to march and burn. But let 50 black people get shot over a single weekend by black thugs and we barely say a peep.

It can be overwhelming, the daily report numbing. But we must not — cannot — allow our senses to be dulled into complacency or do-nothingness.

Our communities are in crisis. And yet, the cavalry ain’t coming. Not the government, not the white media, not the police.

Therefore, the faithful remnant of community soldiers must fight on, working to create a cultural paradigm shift in our hearts and minds; teaching a new generation almost in utero conflict resolution and the sanctity of human life.

We must dismantle the culture of misogyny and self-hate — from songs to the dehumanizing words we call each other. We must continue to renounce the murder of black lives at black hands as vehemently as we do black lives taken by white hands. We must cease to sing, buy or otherwise support the music of so-called artists who call our women bitches and hoes and other assorted terms that denigrate and dehumanize our sisters, daughters and mothers, or that glorify thug life, drug and alcohol use and extol violence. We need a conscious collective and cohesive effort to address this public health crisis on multiple fronts, ranging from parents to the pulpit to the police to public policy.

And we must humanize our loss. Let us say their names. For if this many dogs or cats had been slaughtered, America would declare a national state of emergency.

America gets upset about the slaying of Cecil the lion, or Harambe the gorilla. What about the black man?

Victor McElhaney was a son — our son. He was loved. He had a village. He was not a castaway. Not a Killmonger — a T’Challa. A son of promise. A son of hope. He was the embodiment of character, integrity, creativity and musicality. A gift from above whose radiance will forever shine upon those of us who were graced by his presence

And we should have had to eulogize him… To bury him no less at the tender age of 21, at the beginning of his journey into manhood and into the greatness that filled his aura.

We should not have had to speak a premature autopsy over our son. But because we did, this nation should know his name. And it should know that we are in a state of emergency here in America, even if there is no detectable sense of urgency over our slain daughters and sons.

Say his name… Victor McElhaney. Say their names… Every last one.

Lord, hear our cry…

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com

Website: www.johnwfountain.com