Remembering My First Valentines; Puppy Love, A Box Of Candy And Mama

Mama and I caught the bus down to Walgreen’s at 26th Street and Pulaski Road, where I picked out a red heart-shaped box of chocolates and a card... But I was the one who felt so grateful.

This column is an excerpt from the author’s memoir, “True Vine: A Young Black Man’s Journey of Faith, Home & Clarity”

By John W. Fountain

I WAS IN THE fourth grade and eager to go to school each weekday morning. But one particular day was special. I was both excited and nervous because this was Valentine’s Day. I had bought a box of heart-shaped candy and a card for my sweetheart. She was a little skinny chocolate girl with a pretty white smile. Her name was Henri Chillers. Pronounced “On-ree.”

Henri was the most gorgeous girl in the world. Her hair was always nicely straightened and fixed in long black satin braids or sometimes with pretty curly bangs. She was soft and girlie, not tomboyish like some of the other girls in my class. I didn’t understand this force, whatever it was, that drew me to Henri, that made my legs almost go limp in her presence.

The only problem is that I was too shy to say a word to her. I liked her. But she could not have known it. In fact, I didn’t say a word to anyone in our class about my affections for Henri. My friends would have teased me mercilessly for liking a girl. But I could not help myself.

My mother had only recently discovered that there was a sweetie in my life. A few days earlier, with Valentine’s Day approaching, Mama suddenly popped the question at home.

“Hey, John,” she said.

“Huh, Ma?”

“Valentine’s Day is coming up.”

“Uh-huh,” I replied without interest.

“Do you think…” her words almost clumsy. “Is there some girl you’d like to give a box of candy to or maybe a card?”

“Uhhh, a box of candy?” I asked. “Uh-uh, no way, noooo way, I don’t want to give no girl no candy.”

“Why not,” Mama asked. “There’s nothing wrong with that.”

I shook my head. “Not me.

A Red Heart-shaped Box of Chocolates

“There’s nothing wrong with boys giving girls candy or cards,” Mama said in her half-lecturing, syrupy voice that had a way of disarming me. “That’s what you’re supposed to do, John. You are supposed to be nice to girls, open doors, and walk on the side of the street closest to the curb so that if a car comes and jumps the curb, you get hit and not the lady.”

That all sounded like the same kind of stuff Mama was always telling me I was supposed to do when I grew up…

“Uh-uh, I’m not getting hit by no car. Let her get hit. No way, Ma, no way.”

“That’s what men do, John.”

“I ain’t no man.”

“Not yet, but, but you will be, one day.”

“Yeah, and I ain’t walking on the curb so I can get hit either,” I said.

“Okay, John,” Mama said, ending our debate. “So are you sure there isn’t a little girl that you would like to give a box of cand to?”

I stood there in the kitchen thinking for a moment. I had never thought about this idea of giving a girl a gift before. It all seemed weird, but kind of nice in a way too. I was torn. Mama could tell.

“Well, think about it. Let me know,” Mama said. Then she walked away as if she didn’t care either way.

Later on that day, I told Mama there was a special girl to whom I would like to give a box of candy and that her name was Henri.

Mama and I caught the bus down to Walgreen’s at 26th Street and Pulaski Road, where I picked out a red heart-shaped box of chocolates and a card. I didn’t realize it then, but Mama was trying to teach me how to treat women. Some years later, I reasoned that this was my mother’s way of assuring that I would be a better man than some of those she had encountered in her life.

I was an adult when I realized that I had seldom seen Mama showered with a man’s affections, peppered with roses and candy, or jewelry or the countless things that real men freely give to women they truly love and adore. With her Valentine’s Day suggestion, Mama was, in effect, working to ensure that there would be one lucky woman someday who would have a man that she had molded with her own hands.

‘It Must Be Love’

The day seemed to drag on. But the right time to give Henri my Valentine’s gift never seemed to present itself.

When it came time for dismissal, I walked to my locker and retrieved my coat and the bag with Henri’s gift, then lined up with the rest of the kids. Henri was standing nearby in line. It would have been easy for me to pass off the goodies. I tried to convince my arm to move in her direction. But it would not. My arm felt heavy and lifeless. For a second, I thought about taking the candy home and eating it myself. But I really wanted Henri to have it.

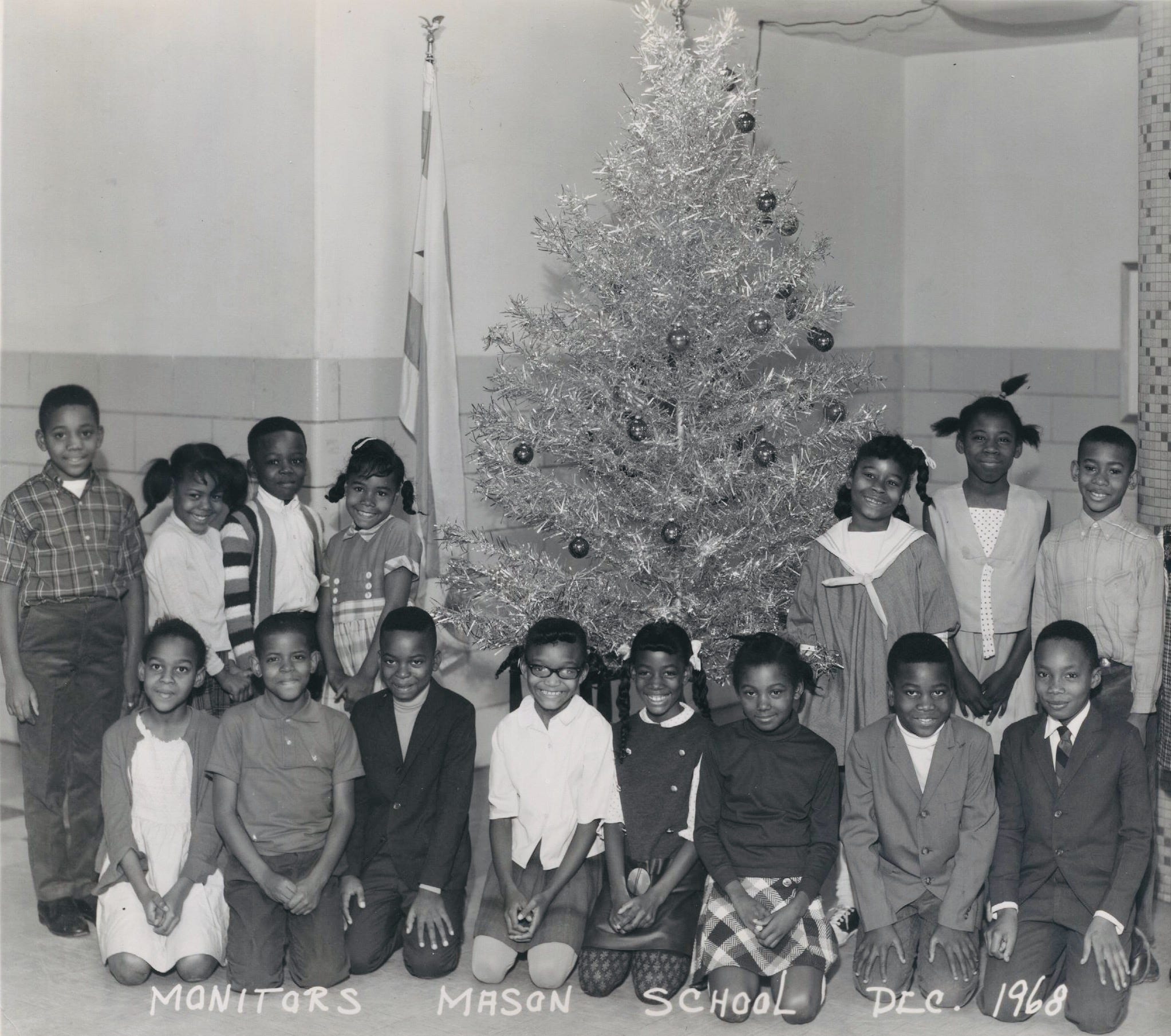

From the school’s door, you could almost see Henri’s house, a brick townhouse that backed onto Mason’s (Roswell B. Mason School) playground. As we walked outside the school, the noise of children laughing and playing blew all around me like the wind. I watched Henri and her friends sidle past the green fence away from the school, then turn south toward her home. I walked the other way toward mine.

But as I turned out of the parking lot, tears welled up in my eyes. Then suddenly, I felt a burst of something I cannot explain. I stopped in my tracks, then turned and began running toward the playground, past the school door, past the gate. “I might still, be able to catch her,” I thought to myself. I kept running, past the throngs of schoolchildren, past the teachers and parents, until finally I spotted Henri.

She and three or four other girls in our class were laughing as they walked, drawing closer to the edge of the playground, where Henri would make the right turn and quickly disappear behind her front door. I hurried to catch up to them but was careful to keep enough distance so as not to appear to be obviously chasing them. Then one of the girls spotted me.

“Boyyy, you following us?” she asked.

They all turned around and looked. I stood there without muttering a word with this queer look on my face, holding my books and the paper sack. They resumed walking. I followed.

“Boyyy, why you following us?” the girl turned and asked again, sassily with her hand on her hip.

They all turned around. Henri smiled. They all giggled. My eyes met Henri’s. “Man, is she pretty,” I thought, although I could not find the words. Here was my chance. Finally, I reached out and handed her the sack.

“Here, Henri, this is for you,” I said.

I stood there just long enough to hear all the girls gasp with excitement as they all looked into the bag and just long enough to see Henri’s face light up. Then my fear and shyness returned. I turned and ran away as fast as I could, my head tilted toward the sky, my book bag flailing, my face spread in a wide grin and my insides ready to burst. I kept running, past the school door, round the corner of the parking lot at 18th Street, all the way past Kuppenheimer, all the way home. I was so happy that I had given Henri the candy. That day I realized I must be in love.

When I arrived at school the next day, the classroom was abuzz. By then, everyone had heard about the candy I gave Henri on Valentine’s Day. The guys teased me a bunch. So did some of the girls. But it wasn’t so bad after all. I could tell Henri was the envy of all the girls. But the best part was when Henri walked over to me during class that morning, her eyes as wide as her smile, her hair pretty and shiny satin as I stood frozen.

“Thaaank youuu, Johnnn,” she said, half singing.

But I was the one who felt so grateful.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com

That's really a sweet story. It took a lot of guts to do what you did at that age!