'Providence'—One Man, One Little School, One Big Dream

Paul J. Adams III and Providence St. Mel have led Black inner-city children to the education Promised Land with 100 percent of graduates since 1978 admitted to some of nation's top universities.

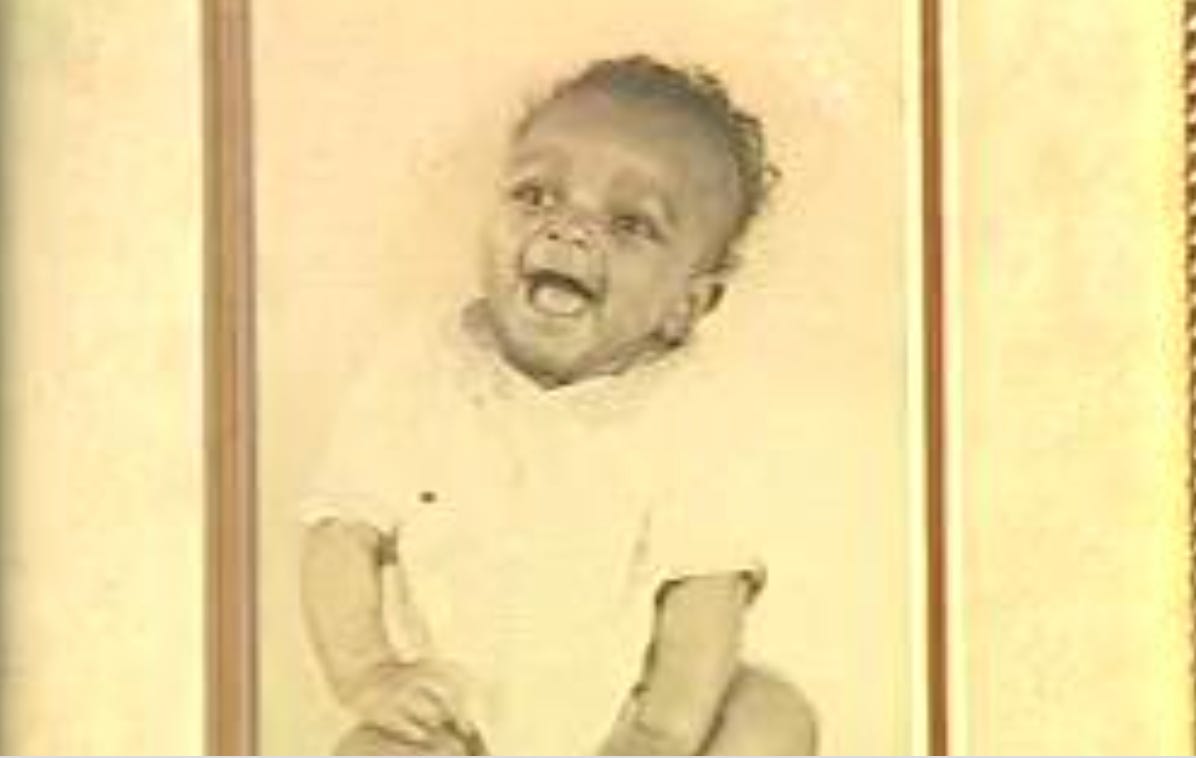

This column is a birthday tribute to Paul J. Adams III, founder of Providence-St. Mel School, John Fountain’s Alma Mater

By John W. Fountain

Grass, emerald-green, lush and alive. Proud blades that point toward the sky. Perfectly manicured, this grass glistens beneath the sun. That was nearly 45 years ago.

And yet, for as far as I could see the other morning, standing outside the yellowish-brick castle in the 100 block of South Central Park Avenue on Chicago’s West Side, the grass still shimmers in the wind and golden sunlight—a simple symbol of promise, pride and hope, more than four decades since I first laid my eyes on it.

I don’t recall exactly the first time I saw the lawn outside Providence-St. Mel, or Paul J. Adams, III—the man responsible. It must have been sometime in 1974—back when Afros and bell-bottom pants were signs of the times and the struggle to lay hold on the American dream still seemed ever elusive for Blacks in America, and we were singing James Brown’s “Say it loud, I’m Black and I’m proud.” What I do recall clearly is the notion that grass wouldn’t—couldn’t—grow on the West Side: too poor, too ghetto, too far from the fertile soil from which sprouts the stuff of American dreams.

Back then, in neighborhoods like Chicago’s impoverished K-Town, where I grew up and had been dubbed by the Chicago Tribune as part of America’s permanent underclass, the “American Millstone,” there was plenty of evidence to suggest that might be the case: broken glass, bald lawns and vacant lots, blight, poverty and despair that flowed like a river of hopelessness.

Back then, I remember the sprinklers outside Providence, the crystal spray that doused Mr. Adams’ lawn endlessly. How, as a high school freshman, I quickly learned one of his most important rules: Don’t step on the grass, or else pay a fine.

To some, it might have seemed ridiculous or severe to impose a penalty for something so infinitesimal. It might also have seemed difficult to fathom how something as simple as grass might be proof enough that some things others deem impossible—with a little planting, watering and vision—might indeed become possible.

As a poor kid whose father had deserted me by the time I was 4, I was the kind who, like many children from similar backgrounds today, was written off by researchers, given my demographics of having been born Black and poor, and raised in the urban ghetto—hopelessly predestined to an unalterable mortal existence, never to rise. Without my mother’s decision and sacrifice in 1974 to send me to Providence-St. Mel, which set me on a different path than so many of my childhood friends, I might have succumbed to the death of dreams that eventually entombs those dreams too long deferred. Maybe not.

This much is not debatable: That for more than four decades, Paul Adams and Providence St. Mel have helped lead poor Chicago children to the Promised Land of educational success and that since 1978 every one of the school’s graduates has been admitted to a college or university. This much is also clear these days:

That for at least the last 45 years, the Chicago Public School system has largely wandered in the wilderness of “miseducation” and still has yet to fully cross the sea of red-tape bureaucracy occupied by a union that often seems more concerned for teachers than students, and by bureaucrats who, by their failure to fix the system after all this time, leave me wondering whether they ever really want to.

At 13, I saw Paul Adams as a lion of a man, his proud woolen Afro as his mane, and every square inch of Providence, including every blade of grass, as his domain. More importantly, I found inside the school’s walls a safe-haven from the perilous streets of my neighborhood. I found educational opportunity and the expectation of success. I found through one man’s vision sufficiency to dream. In Adams, I saw a Black man filled to the brim with integrity, character and commitment. An unyielding Black man who was not only willing to stand for the education and future of Black children, but also willing to fight, even to give his life for our good.

He turns 83 today.

‘The School That Refused To Die’

Today Paul J. Adams III is a world-renowned educator whose inner-city Chicago school, nestled in one of the toughest and poorest neighborhoods in America, has sent 100 percent of its graduates to the most elite universities and colleges in the nation since 1978. Adams’ story and the story of Providence St. Mel School are intertwined as a David vs. Goliath triumphant true tale of the little school that could.

A school that Adams refused to close in 1978 when the powerful Chicago Archdiocese announced plans to withdraw its funding from the predominantly Black school and permanently shut its doors. It should have been the death nail for the school that existed as an alternative for poor Black parents seeking to give their children a viable educational option to Chicago’s notoriously failed public schools in the late-70s—long before the existence of the charter school movement; and yet decades since the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawing segregation, although public schools today remain separate and unequal.

Adams and supporters launched a furious campaign for financial support, marching outside the Catholic Archdiocesan headquarters and the cardinal’s house, drawing local, national and international attention, and leading to a now iconic full-page Wall Street Journal ad, and eventually to two visits by President Ronald Reagan to the West Side school, which he praised as a model for inner-city education. I was a member of what was supposed to be the school’s last graduating class.

Today Providence St. Mel is a premiere independent private school with a more than $6 million annual operating budget. And the dream—and reality—of educating children that society too often has written off is alive and well, even in a place where they say the grass won’t grow.

I am a witness. For beyond the school’s emerald grass, behind the walls of the yellow-brick castle-like structure that towers above the West Side’s Garfield Park, I found refuge, a place to dream. Even in its hushed halls, where the floors glistened and the spirit of educational excellence and expectation was palpable, I learned to see the world through the prism of possibility. I found a lifeline.

I wasn’t special. I was a poor boy. A Black boy. Just another boy in the hood who, in the schematics of the universe, was more destined to become a drug dealer, gangbanger, thug, murdering three-time felon—more likely to become a tragic statistic, than a success story. But Adams didn’t see it that way.

In the eyes of Adams, principal when I first walked through the school’s doors in 1974, we were diamonds in the rough—some a little rougher than others. In his eyes, we all possessed the potential to rise, like his grass that some said wouldn’t grow on the West Side—to shine forth, in time, in splendor, as proof that educating poor, inner-city Black children is a simple recipe: A safe and competent learning environment plus unwavering expectation and a little TLC, equals success.

It isn’t rocket science. And yet, more than 40 years into Adams’ tenure at St. Mel, where since 1979 all of the school’s graduates have been admitted to college, the crisis in urban education seems to remain unsolvable and high school dropout rates still grotesque.

In 2009, for instance, the America’s Promise Alliance reported in a survey of major school districts in the nation’s 50 largest cities that only 53 percent of students graduate high school compared to a national average of 71 percent. (Chicago’s rate was 51 percent. Indianapolis was last at 30.5 percent.) Nationally, according to the study, 1.2 million students each year drop out. About 7,000 every day. One every 26 seconds.

But that’s still only half the story.

Add to it that high school dropouts are more likely to live in poverty. That nearly 50 percent of African-American and Hispanic high school students drop out each year. That in Chicago, students have been known to graduate decorated as valedictorian and yet barely able to read, and a fuller picture of urban public education crystallizes:

It is a system of miseducation that breeds social inequality and ensures the cementing of a permanent underclass, and has spread even to some suburbs.

In my eyes, that’s not a shame. It’s downright criminal. And it’s clear that it’s way past time for politicians, administrators and teachers—under whose watch for decades now America’s schools have failed American children—to fix this mess. I suspect they would if their own children had to attend the schools where they teach or have charge.

Even amid the call for extended school days, I can’t help but wonder what real sense or quantifiable difference this might make at certain schools where the question of whether students are really learning is arguable. To me, it would be like extending the hours at an asylum for people who shouldn’t be there in the first place.

This is not meant as an indictment against all public schools. Still, I question the collective will to educate all of America’s children. And yet, here lately, I am filled with memories of Mr. Adams and Providence, which for thousands of ghetto kids over the last 45 years was our fortress, our light, our best hope. And I am convinced of one thing: That educating our children is not the impossible dream.

That Paul J. Adams’ arrival—and ours—at the towering brick castle situated on an island of poverty was more than happenstance, and more a matter of providence.

After All These Years

If I close my eyes, I can still hear Mr. Adams’ roar, proclaiming Providence St. Mel to be his domain. I can see him, standing, protecting students from the cruelest elements on the city’s troubled West Side. Instilling in all who entered the Castle’s doors: PSM pride.

If I close my eyes, I can still see this lion of a man standing—his soul rooted in the souls of the Middle Passage and red clay Alabama dirt. Standing—inspired by Dr. King’s dream. Standing. Shaped by Emmett Till’s murder and Jim Crow hurt. Standing—determined to be the change he wanted to see. Standing—committed to the eradication of injustice and inequality.

Moved by an inextinguishable hope in the unseen. Fortified by his faith in the miracle of hard work and dreams. Cemented by his belief in the transformative power of God and education. Stubborn in his will to impact the trajectory of a nation: One child, one school, one heart, one mind, one day at a time…

So when the Chicago Catholic Archdiocese declared in 1978 that it would forever close Providence-St. Mel’s doors, the Lion roared. And from near and far they came to embrace Mr. Adams’ vision of educating the poor; of ignoring the statistics and the naysayers who may have laughed; of envisioning ghetto schoolchildren sprouting up someday like emerald grass.

Of raising the bar of expectation and not accepting excuses to fail. Of providing the tools and instruction to excel.

And here we are 45 years later, Providence still standing. Still believing. Still achieving. Still equipping generations of children with academic wings to soar. Still defying the odds. Still succeeding at what “they” still say cannot be done: Educating all of America’s daughters and sons.

As a man, once a boy, who found my way to Adams’ castle, some things I will never forget. Among them: That for some of us, he was Father--a stern, and yet, loving surrogate in place of men who had abandoned us--a mentor, a rock. Steadfast. Unmovable. A black man who stood, stayed, stuck.

A man who looked into our brown eyes and saw us as educable in whose eyes, each time we reached some new milestone, we saw delight and pride. Keeper of the gate. The man who could make green grass grow—even on the West Side.

This is his legacy: Countless inspired lives and educational transformation.

And this is the bedrock upon which the Providence St. Mel dream rests: That to help save our lives one man was willing to give his.

Happy 83rd birthday, Paul J. Adams III.

Love, Your Son,

JOHN