On Father's Day, 'A Letter To My Children On Faith, Hope and Legacy"

Writes Vincent C. Allen: 'I pray my presence, love and commitment as your father have provided lasting memories long after I have transitioned from this life to the life to come. You are my legacy.'

Editor’s note:

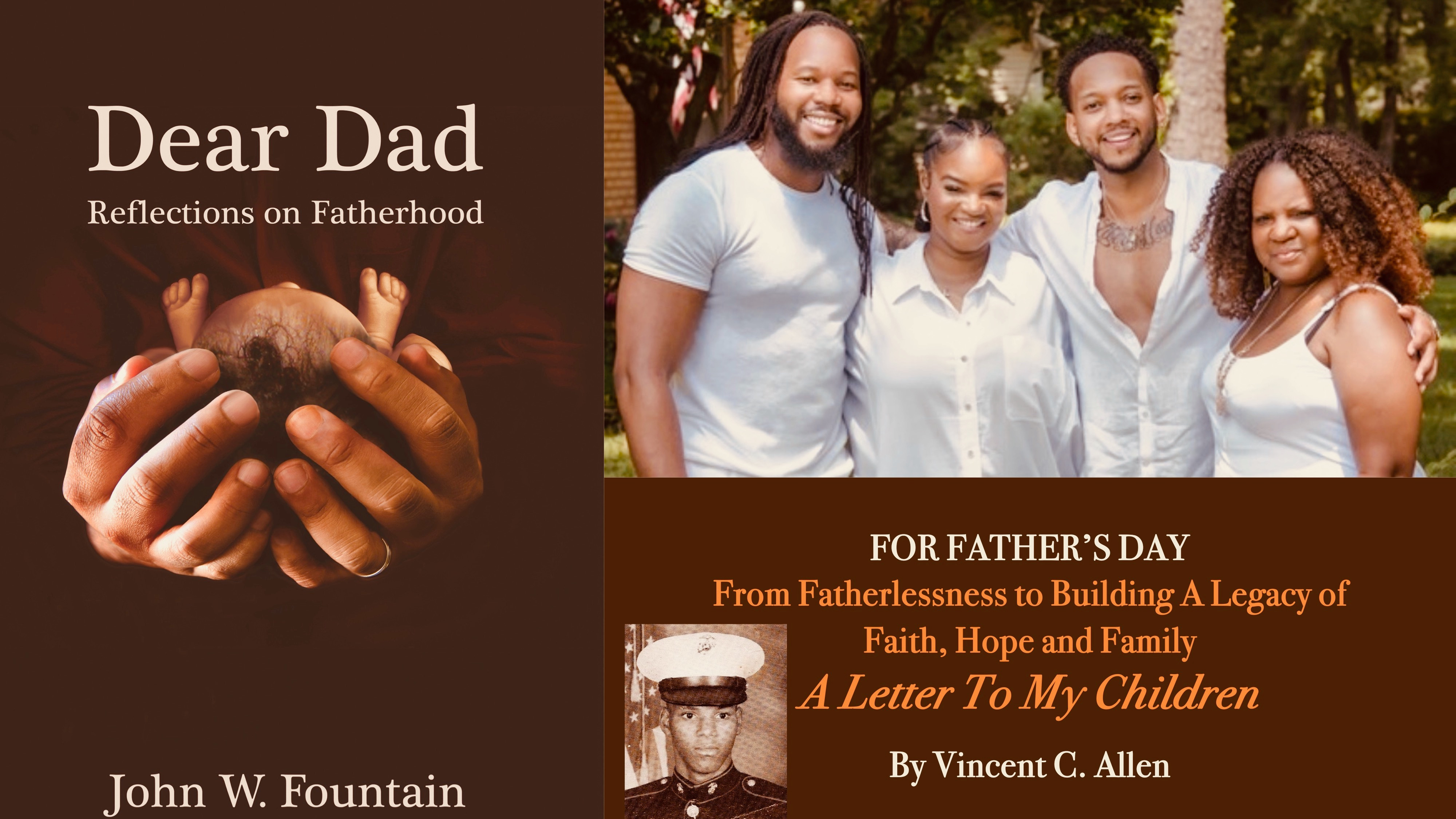

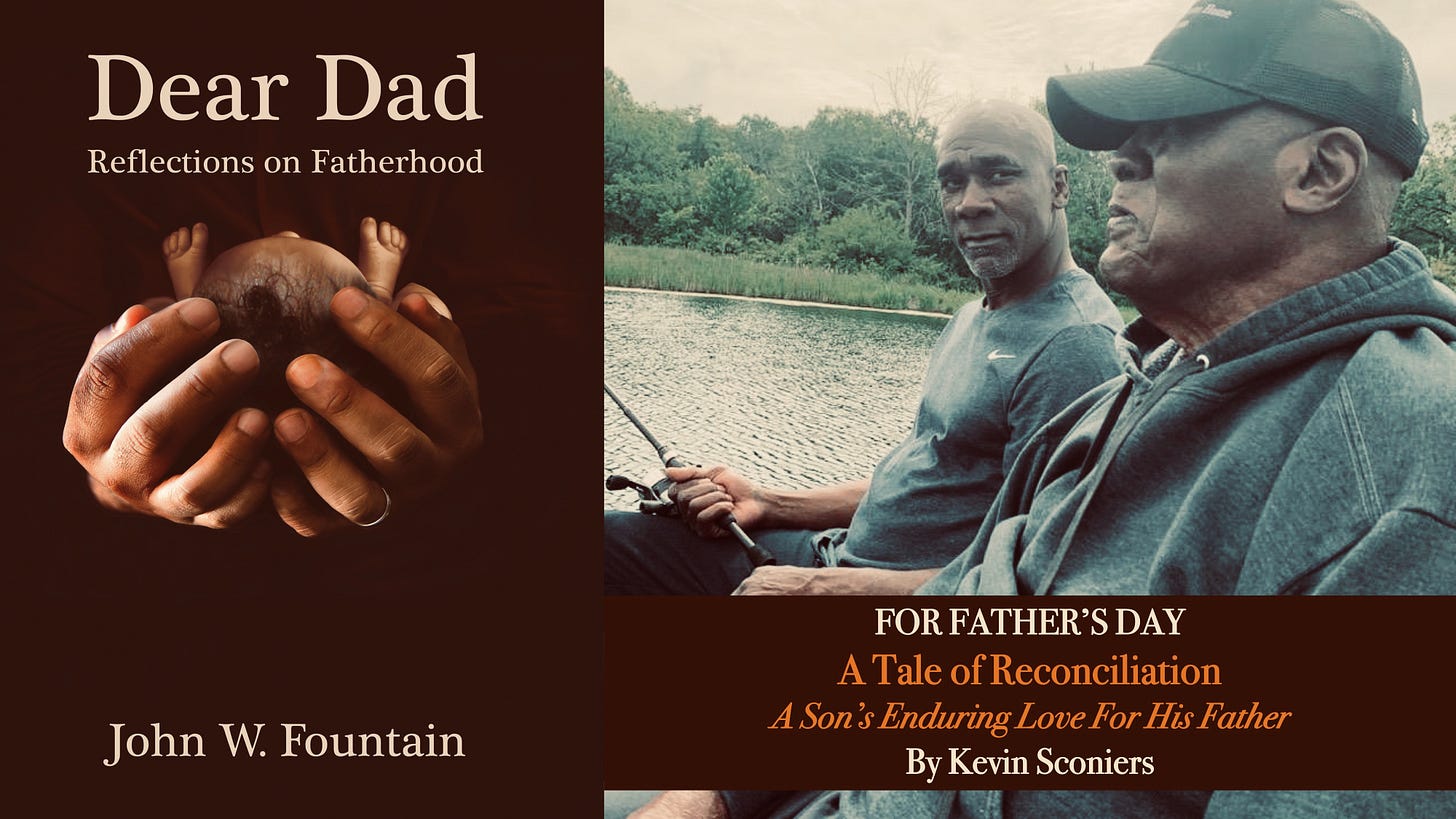

More than 13 years ago, I asked some of my friends to join me in writing about the experience of fatherhood in their own lives—whether good, bad or indifferent in a book titled, “Dear Dad: Reflections on Fatherhood.” They are stories that I—that we—believed then and that we still believe have the potential by the power of intimate narrative not only to help others understand the impact of fatherlessness, but also to help mend those most wounded. Among the writers was my good friend and brother Vincent C. Allen who pens an inspiring and captivating story of how the absence of his father compelled him to be the father he never had—a father to his own children, a father to the community. For this Father’s Day, I asked him if he would write a letter to his children. It is a letter of hope, faith and love, and of the transformative power of one man’s resilience and determination to build a legacy upon which future generations might stand. I am honored to publish that letter here, followed by his original essay in Dear Dad. Happy Father’s Day.

–John W. Fountain, Publisher, WestSide Press; Founder, FountainWorks

A Letter to My Children

I write this as a father who acknowledges his frailties and humanness, hoping that whatever lived experience I have had will provide insight to you and our posterity. I also pray that the many sacrifices I have made as your father will provide wisdom and endurance for a lifetime. My faith and belief in our Savior—Jesus the Christ—has provided a life that I pray is worthy of your approval. Finally, I pray that my presence, love and commitment as your father have provided long-lasting memories that you will enjoy sharing long after I have transitioned from this life to the life to come. For you are my legacy. –Vincent C. Allen

By Vincent C. Allen

I WAS FORMED IN the darkness—and ultimately reformed by the light of faith—during a time when our country was in such deep sorrow and conflict, and the state of our humanity questioned—still not yet considered to be full citizens in a land of the free and home of the brave.

I was born of a young woman, who herself, really didn’t know what life had to offer. Her beauty and petite frame were both blessings and curses. She wouldn’t graduate high school, having dropped out early on.

At 16, she birthed my eldest sister—older than by 11 months 3 days than me. With my sister on her hips, my mother brought me into this world at the historic segregated Homer G. Phillips Hospital, once upon a time the city’s only public hospital for African-Americans in St. Louis, Missouri. Later, my mother would become a ghostly figure, living for three years in Little Rock, Arkansas, with her husband without us.

In 1969, however, my great-aunt and her posse would travel to Little Rock and retrieve our mother who had left three young children with her sister. They returned with her and with another son who had been born during her absence from us. This was my beginning.

Not having any direct influence from my biological father, I have forged a path with the assistance of prayer and meditation. My birth father only spent 30 to 45 minutes in my life with me.

Even to this day, I have no recollections of anything he said to me, except for those words he uttered when he walked out of a liquor store apparently having run short on his purchase of spirits. He asked me to give him back the three dollars he had given me a short time earlier with the promise that he would return the money the next day. There would be no return.

The next day would span almost two decades until that day that I viewed my father’s body, lying in a casket at Cole’s funeral home on West Grand Boulevard in Detroit, Michigan, next to the iconic Hitsville U.S.A., the historic home of Berry Gordy and Motown. This is forever etched in my memory.

‘Not Losing Any Time’

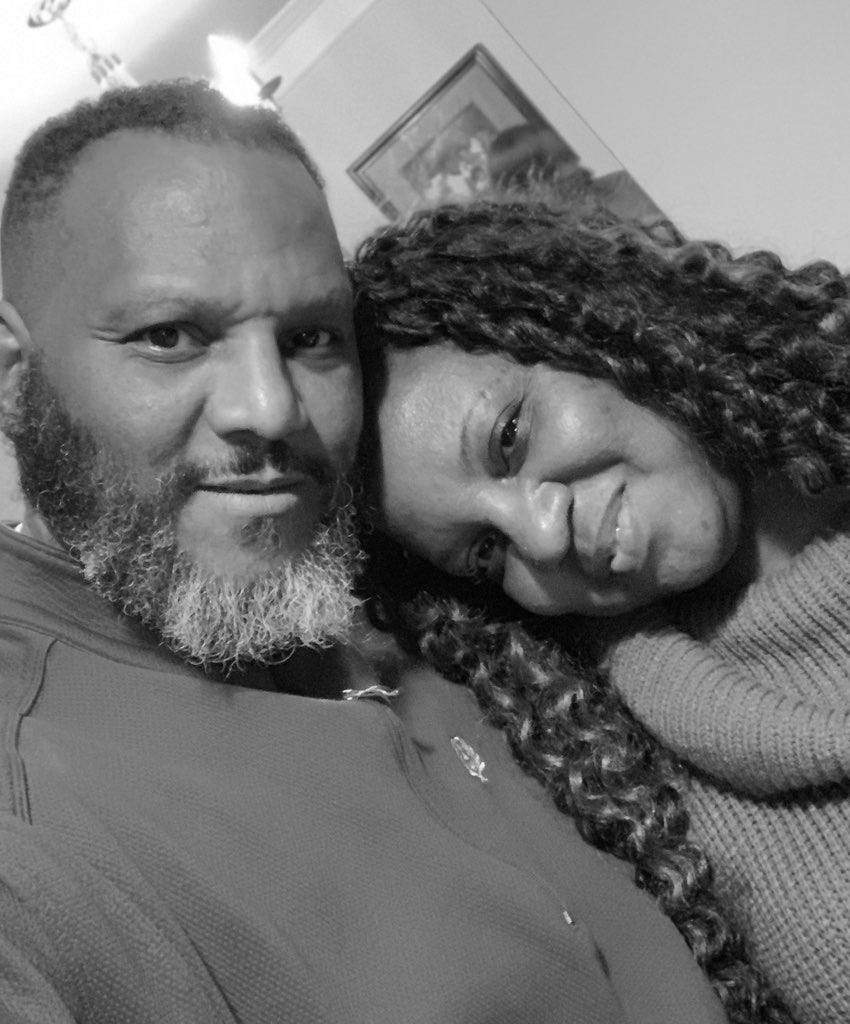

DEAR TANISHA, CRYSTAL, V.J. AND BRANDEN, I share this with you to provide context for my life. To share with you why I have always endeavored to demonstrate my unwavering commitment to you as your father, my deep desire to keep us together as a family.

You yourselves have been witnesses to my efforts to make an impact as a pastor for 25 years in the lives of the human family in the communities we lived during my twenty years, two months and nine days service as a U. S. Marine. And although I am retired now, it is important for me that you all know the genesis of why I continue to seek, even now, to engage with you—my family—as much as I can. Even if I also understand that you each have your own lives you are forging.

My hope and legacy are that you will draw closer and closer to one another. That you will recognize the myriad sacrifices made and that will continue to be made to help us care for one another even as we share our successes and failures.

You see, we are all woven together. And it is true that what affects one affects us all.

I hope you will always allow space for each other to make mistakes and know that each of us has the agency, at any time, to return to the fold and to know they are loved and cared for. To come home to family.

I hope your children realize your sacrifices and live a life with a mind to be inclusive of you even as they eventually move away from your home. I pray they grow into their privilege as educated contributors to humanity, having a legacy of education and service to mankind. I pray they expend all of their resources while they have capacity. I pray they stretch themselves and soar to places imagined by you and me and perhaps even unimagined. Your Mother (Mother #2) and I have given ourselves totally to your success and dreams as much as possible. We have sought to create a legacy with so many others. And yet, I pray that we have not missed any of you.

While my biological father taught me by his absence, I vowed to be present with each of you and with my grandchildren inasmuch as possible. As I move into these twilight years, I hope and pray that my lived legacy—together with my wife—has touched your lives and that you are living out your possibilities and dreams with our support.

Having survived stage four squamous cell carcinoma, I am hopeful of not losing any time with any of you in your uniqueness.

I Will Always Remember…

TANISHA, I WILL ALWAYS remember fondly, plaiting your hair and putting you in the stroller and catching the bus. I remember helping you complete your one-mile run to receive credit to graduate high school. Taking you to the Air Force recruiter (we should have gone to the Marine Corps recruiter!) and helping you join the Air Force to serve our country (That was huge!). And, of course, coming to each of your children’s two-weeks’ checkup.

Crystal, I remember our walk in Woodbridge at night and you sharing how you felt. It was so “quiet” as we walked. I remember sharing, staying up late times at night hearing you pour out your heart (That was priceless.). I remember learning of you joining the Army and then going to Iraq. Attending your recitals and watching you dance.

VJ, watching you mature into your own person is one of my greatest joys. Remembering you first solo at Greater Friendly Church of God in Christ will always remain in my mind. Visiting

Morehouse College and later dropping you off and watching you move into your room. And then, years later, watching your hooding ceremony for your Ph.D.

Branden, I remember flying to Korea and you sitting with your stuffed lion, and not caring at all when I pointed out Mt. Fuji. I remember you playing basketball in Naples, Italy. You and TBT creating your ‘Go-Go’ band. You sharing that we had a granddaughter, which brought trepidation and excitement all at the same time.

Lastly, each of you sharing in my 60th birthdate celebration was the most memorable. And I pray that time and life bring you just as rich and memorable moments as mine, affording you the opportunity to live a complete life, loving each other on your way.

My Hope and Legacy

WHILE MANY PEOPLE LOOK at legacy as that which begins once an individual has transitioned from the physical realm, I, on the contrary, believe that one’s legacy is in constant evolution. That it is being made each day. My greatest legacy is a legacy of presence as your father.

And I pray that when you think and contemplate any accomplishments that I have achieved, that you know and always remember that nothing meant more to me than my efforts to ensure that your last thoughts of me as your father would not be aloof and empty. But rather filled with memories of laughter and even tears. Tears of joy. Tears of love. But mainly, with memories of me showing up. Of me being there when you needed me most.

Even at 61, I find myself looking for that ‘next day’’ that my father promised, painfully aware that it will never materialize.

That 30 to 45 minutes with my father 50 years ago as an 11-year-old boy had a lifelong impact. And over the years it has taught me invaluable lessons about time: Time matters, time spent matters. Life is fleeting.

Let’s make the best of our time and create memories that fill a room with laughter. Memories that challenge the conversation with facts and with humor.

I am determined to live out a continuous legacy with you, your children, and your grandchildren with the gifts of life and time. While there may be regrets, they are few. Having all of you actively in my life is priceless and worth every disappointment and tear shed over the years.

I have attempted to model and mentor each of you in a way that would spur you to continue to serve humanity, to be authentic to your true self and to appreciate what lies within you and how you might provide strength, hope and sustenance to our village. Know that each of you brings your own special importance and contribution to the fabric of the Allen tribe. Each of you matters.

And as long as we are support for each other, as long as we respect who each of us is, and for as long as we give room for each of us to grow, by faith, by hope and by love, our legacy lives.

Email: Allen.vc@verizon.net

Where Were You?

Original Essay From “Dear Dad: Reflections on Fatherhood,” WestSide Press, 2011

By Vincent C. Allen

THERE I STOOD AT the ceremony with my feet at a forty-five-degree angle, my thumbs running along the seams of my trousers, shoulders as erect as the Statue of Liberty, head held high as one who has just been given an opportunity for a promising future in the U.S. Marine Corps. I resisted the urge to look around at the crowd of family and friends in attendance, in part because I feared the fury of the attack I knew I would have encountered from one of those drill instructors who had made their position clear some eleven weeks earlier, but mostly because I knew there was no need to look for “them.” I knew “they” were not there. More important, I knew “he” was not there.

Truth is, he had never been there. In fact, at that point in my life, I had only ever seen him once and had clung to that encounter as something I didn’t want to ever forget.

For most of my life, my father was MIA.

He seemed to live as though his absence did not affect me. I, however, believe that it did. I know it did. In time, I chalked up his absence as having been his loss. And I accepted as best I could that I likely would never really know the man responsible for my existence. By age nineteen, my father had already missed a lifetime of moments. But why did he miss this moment?

I had just accomplished something the other eighty-five stalwart young men had not. I not only graduated from the eleven-week transformation of the U.S. Marine Corps basic training, but I did so as the number-one recruit for Platoon 1060 in September 1982—crowned the “honor” graduate. But now, who was I going to celebrate with?

It seemed as if every one of the newly christened U.S. Marines had someone to congratulate him. I had no one. No mother. No brothers or sisters. Not an aunt or uncle. No father.

I played it off, at times stone-faced, other times smiling nonchalantly, as if their—as if his—absence did not matter. Years later, I had to recognize it did.

My feelings, I later came to understand, had been pushed to the cellar of my own consciousness and had no reason to reemerge. It was perhaps a disappearing act necessary for my own survival. In fact, I eventually became quite comfortable living as if I did not need a father, or a mother or anyone else. Long before I became a teenager, I had already endured more parental neglect and hurts than I care to remember.

I was abused by my stepfather in Little Rock, Arkansas; abandoned by my mother and left to live with my great-aunt, who punished me for not knowing my ABCs. I even failed the first grade. At age five, I fell from a second-floor window onto the unforgiving concrete pavement of Page Street in St. Louis, Missouri. Later, I was hit by a cab on Couples Street in St. Louis. And finally, three years after she had left me behind, I was reunited with my mother and moved to Detroit for what remained of my formative years, though still without him—without my father or any semblance of a man, someone who might have comforted, consoled, or protected me during those traumatic moments of my early childhood years.

Where was he? I often wondered silently. What was his reason for not being there? What did I do? Why did I run him away? Why didn’t he desire to have a relationship with me?

In time, the abuse I suffered ended, my wounds eventually healed, and the relationship with my mother was restored. But one stinging question still haunted me throughout my adult life: Where was he? Who was he?

Finally Face-to-Face

FOR MUCH OF THE early years, I only heard bad things about him. Mostly, my father was a ghost, a figment of my imagination since I had never even seen a picture of him.

I was ten or eleven when I finally got the chance to meet him. That summer day, he walked into the house—standing about five feet ten, to my best recollection, though the image of him has faded with time. Seeing him that day for the very first time did not immediately stir up warm and fuzzy feelings. In fact, “Daddy” was not a thought as I stood watching him walk through our door. It was as if he were simply another man my mother had brought into our house. The only difference was that he entered with a few other people and wore a kind of arrogant expression that I later learned was the spirit of Mr. Wild Irish Rose.

After a few minutes of chitchat, he asked if I would go for a walk with him. I said yes. As we strolled, I thought, “Wow, I’m walking with the man who gave me life.” Even as I recall our meeting, now, many years later, deep feelings of nostalgia grip me.

Minutes before we had embarked on that journey of a lifetime, my father had given me the only thing besides my very being that he ever gave me that was tangible: Two dollars. Two bucks in 1975 was a lot of money. So not only did his gift to me make him “amazing” in my eyes, he was rich!

My fairy tale, however, soon disappeared when our long-awaited-for father-and-son stroll ended at a corner liquor store, where my father quickly disappeared, then, like a lightning bolt, reappeared only to ask for the only tangible, worthwhile thing he had ever given me. Having bestowed it just ten minutes earlier, he now wanted it back, though I could never have imagined that my “rich” father from New York had given me his last two dollars. Looking back now, it was like I was sitting at a poker table, plenty of chips on my side and waiting for the river card to give me life because I was all in. Then it happened. Suddenly, my father fired off like a marine drill instructor, giving directions to a bus full of scared lonely boys waiting to become the world’s finest fighting machines.

“Let me have the two dollars I gave you,” he said without hesitation or remorse. “I will give them back to you later."

Such was our first meeting.

The second time I saw him, I was a decorated marine gunnery sergeant with medals to prove I had not failed. But he could not see them. He could not see me. He was unaware of my presence, unaware that I had four wonderful children and a wife. He could not grasp that I was living in Italy, proving my love for our country and NATO by my service. He could not see the man I had become, nor hear the words of forgiveness I might whisper in his ear.

And as I neared his casket that winter day in 1998, what I also understood was that I would never get my two dollars back, that I could never ask him why he chose to not be in my life or why he had allowed himself to pass from this earthly realm to the afterlife, leaving behind a son still so vexed by his absence, still longing for answers.

Reflections

IT IS WINTER NOW, and my father many years buried. And yet I still wish I could speak to him. I still long for a father-son conversation, the kind I have had with my own two sons, now adults. I desire to share with him that I have not turned out like his first son from another woman. I want to tell him that I have never spent time incarcerated. That I have not made mine a life of cheating and abusing my body or others around me.

I long to tell him that I forgive him, to introduce him to my beautiful wife, Felicia, to whom I have been married twenty-four years; to have him meet my four children, Tanisha, Crystal, Vincent, Jr., and Branden; and our three grandchildren, DeShawn, Jalen, and Taiya. I want to tell him how I have turned out to be a preacher and pastor and made a career of the Corps. That I am committed to and involved in bettering people’s lives. And that I have chosen to be an asset rather than a liability to society. But he is not here. He is no longer here.

And so, at forty-six, I remain dubious about why he chose absence over presence. Is it better to have never known, or to have known and lost? What might life have been like with him? Questions and feelings of nostalgia linger. So many questions. At times, they compass me about and entice me to dwell too long on the past and on loss.

But I am imbued with the possibilities of the future. And while I realize now that I will never have all the answers, I have resolved to find solace in the fact that the living God has been a father to the fatherless—and that He has been my father. That Christ Jesus has promised to be with the human family that trusts in Him.

Although I continue to find comfort in His word, it does not eliminate the late-night toil of the little boy inside me who still longs for the experience of an earthly father and who still asks in moments of human frailty and amid the sting of abandonment, “What if?” and “What did I do?”

While I did not find the answers as the abandoned son, I did find them along my mission to be a father who might never do the same to his children.

So although I became a father at age fifteen and had my second daughter by eighteen, I purposed in my mind to not be like my father, even if I did not understand fully what being a good father entailed. My own father’s absence caused me to remain faithful to my daughters and to their welfare. So that even though we were not in the same household, and even though my career in the military carried me across the seas, from shore to shore, potentially into harm’s way often with no assurance that I would return, I did my best to stay connected. At times, I was better than at other times. But I never lost focus, always endeavoring to be their lifeline, to be more than some distant hazy figure in their minds. My father taught me that by his absence. He taught me in ways he will never know.

My children have never known a grandfather. Yet each one of them has had their father all of their lives. That was my purpose as a father, my mission as a man.

Epilogue

I DO NOT KNOW if I am a better man than my father. And perhaps that is not for me to say. What I can say, what I can say assuredly, is that I have striven always—no matter life’s innumerable challenges and trials—to be a better father, to carry myself as a moral and responsible man of which my children and my family could be proud. And I can say with as much certainty that my two sons—twenty-one and nineteen—have for their lives observed a man dedicated to them and to their mother. I have attended school events, assemblies, and other activities in which they were involved. And I have tried to impart to them the life lessons that will aid in their personal endeavors as men and also someday as fathers.

Regarding my own father, I know that I still carry many unresolved issues within my heart, which every now and again resurface. But I also know that I must remain steadfast in my belief that my heavenly Father will carry me through those moments of loneliness and longing. This much I also know and have resolved: I do not hate my father. And I am grateful to him and my mother for bringing me into this world, for giving me life.

But as a grandfather of two bright young men and one gregarious young lady, I am deliberate in giving them memories, enough to share with their children and their children’s children—memories enough for a lifetime, memories of me being there.

Vincent Allen—Pastor and founder of Agape Fellowship Ministries in Stafford, Virginia, he is a native of Detroit, Michigan, and a retired U.S. Marine who served more than two decades in service to his country, working over the course of his career on all levels of administration, including as administrative chief for two former Assistant Commandants and the 32nd Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps. He also served in Naples, Italy, with Allied Forces, Southern Europe, where he founded a ministry serving both Italians and Americans. He retired this past September as pastor of Agape Fellowship Ministries in Stafford, Virginia, after 25 years and lives in Tallahassee, Florida.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com