My White Editor Confessed She Was "Afraid" Of Me; My Sin: Reporting While Black

My college degrees, my King’s English and my white shirt and tie did not shield me. Not even my entry to the Chicago Tribune newsroom. I was still one of "them." Unsafe. Untrustworthy. Someone to fear

“For promotion comes neither from the east, nor from the west, nor from the south. But God is the judge: He putteth down one, and setteth up another.” —Psalm 75:6-7

By John W. Fountain

I SAT ACROSS THE desk in a small windowless office just off the Chicago Tribune’s 4th-floor newsroom, studying my white editor’s taut oval face and her piercing yet impenetrable squinty eyes for some clue of why she had suddenly asked to meet with me privately. As a Black man born here in Emmett Till’s hometown, I didn’t feel exactly comfortable, and in my mind for good reason, meeting with a white woman behind closed doors.

That had less to do with my editor Barbara Sutton, per se. It had more to do with the published portrait of the grotesque swollen and badly beaten face of the 14-year-old boy pulled from the Tallahatchie River in Money, Mississippi, that fateful summer day in August 31, 1955, that was seared into my consciousness along with the realities of being Black and male in America, which historically has too often held fatal consequences.

I had learned, especially when talking to white women in the newsroom, as a matter of my own professional survival, to speak with more treble and less bass. To shrink myself. To take a seat nearby when getting instructions rather than to stand over them so as to try and minimize the threat or discomfort conjured by my mere presence. Barb was a woman of average build, somewhat dowdy, soft-spoken, thoughtful and emitting librarian vibes.

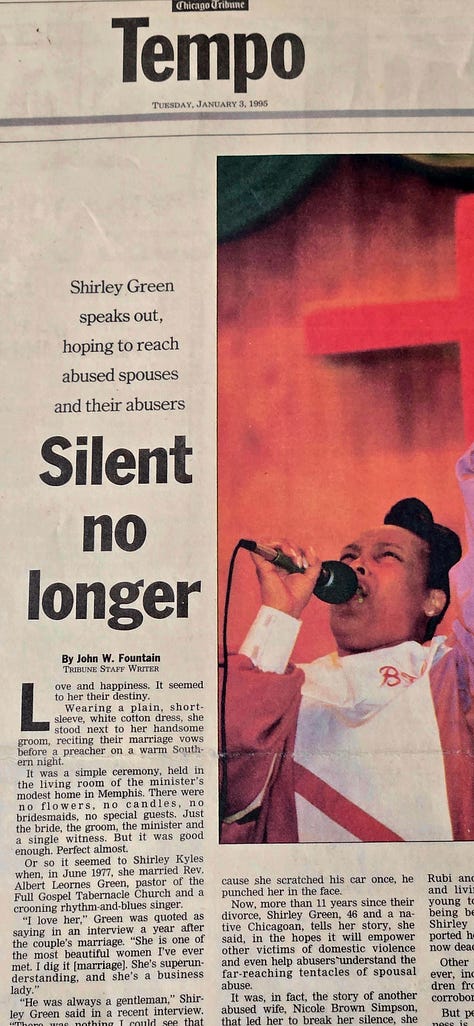

I was officially introduced to Barb about four years into my tenure at the Trib. She was assigned as our editor for the Tribune’s new “Saving Our Children” project, launched in early 1994 by the metro desk with me and two white reporters, Louise Kiernan and Rob Karwath assigned to examine the Illinois Department of Children & Family Services and its perennial failures, which played out time and again in horrific detail of almost unspeakable abuses against children and infants. My previous conversations with Barb had been confined to discussion of our working project as reporter and editor and had been professional, brief and sparse. No signs of trouble whatsoever.

A message from Barb had popped onto my desktop screen, asking me to meet. I was sitting at my assigned cubicle just off the Metro desk. My reporter’s perch—blocked by three makeshift walls about 4 feet tall with the work stations of other staff writers similarly partitioned—was just a few feet from the executive editor’s glass-encased office. That office was where as an intern I had first witnessed the sight of a Black man down on his knees, shining the shoes of Editor James D. Squires—a then soon-to-be Kentucky horse breeder—who looked beet-faced contented, like a pompous king on a throne.

I shook my head in disbelief, then turned to look at a veteran Black male reporter who sat nearby and who, unbeknownst to me, had watched with some degree of humor as I happened upon “the shining.” “Ain’t that some shit,” the expression on my face said. The reporter, Jerry Thornton, shrugged and chuckled with a certain twinkle in his eyes, then explained that was just part of the regular goings-on around here and that I should get used to it.

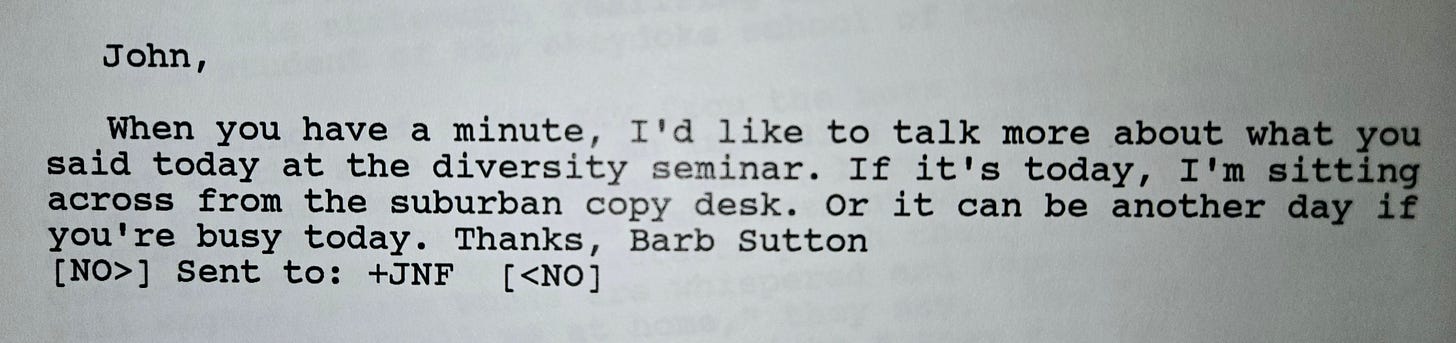

Barb’s note, sent to me via the Trib’s in-house message system, read: “When you have a minute, I’d like to talk more about what you said at the diversity seminar…”

I had no clue as I obliged and soon walked over to her desk, then followed Barb to the small office outside the newsroom like a sheep being led to the slaughter.

“John, you could probably sue me, or I could lose my job for what I'm about to say to you...” Barb said softly but directly while staring at me quizzically shortly after we sat down with the door closed. My heart raced. My thoughts swirled unsure where to land. Then she spoke her piece. Just five words:

“I was afraid of you.”

Stunned, I wasn't quite sure how to respond. Finally, I mustered the words as seconds passed, seeming like minutes. “Barb, but why?” I asked. “I don't understand... I've never said a cross word to you, never so much as raised my voice.”

She replied. “…It wasn't anything you said, John. I… I was intimidated by your silence…” Her words trailed off.

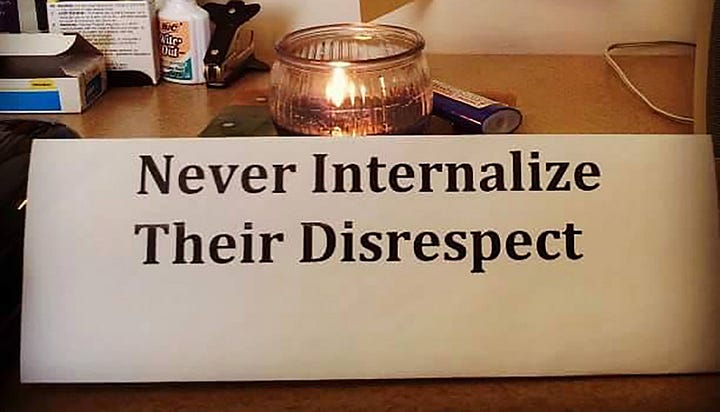

She continued: “...Then you have that sign on your desk...”

The sign? What sign?

…Ohhh, that sign.

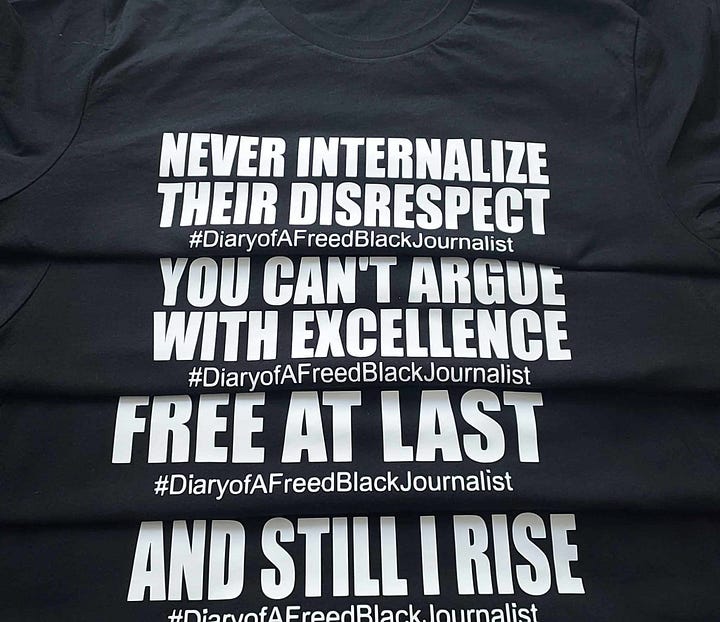

That intimidating offensive sign that had struck fear? Never Internalize Their Disrespect.

Those words were spoken to me by Don Terry, a friend and national correspondent at The New York Times when years earlier I called him despondent on the telephone from my desk in the Trib’s Schaumburg bureau one day. Don listened quietly. Then he spoke. His first four words: “Never internalize their disrespect.” I don’t remember anything else he said. His words extinguished my storm. Never Internalize Their Disrespect…

Just four words printed out in black ink on a white sheet of paper I had tacked up as my internal compass and encouragement in an often hostile newsroom, where I felt maligned, assaulted and, for much of my six years at the Tribune, without support. Not even from most other resident Black journalists—editors or reporters. I eventually came to the realization that most were not about to jeopardize their “good Negro” plantation standing for a malcontent field negro like John Fountain, and that some might even seek to cement their “house” status with massa by distancing themselves from me in the newsroom.

I had committed the violation of speaking up for stories about Black people in Chicago and of questioning the lack of fair and accurate coverage for Black life on the other side of the tracks. Spoken my piece about the Tribune’s suburban coverage push and its creation of satellite bureaus at the expense, or the abandonment, of covering the inner-city. But I was never boisterous with my rebuttal. Not a loud mouth or fist-pumping Black activist.

And yet, I unintentionally became a thorn in the side of the Trib’s status quo. That troublemaking, insurrection-stirring Negro, even in my soft-spokenness. Good Negroes don’t shake the tree. Most often, when I found myself out on the limb, there was no one out there but me.

Trial By Fire

IT BECAME CLEAR TO me early on that some of my Black Tribune colleagues were not Black like me. At least in some cases, I found some of them unwilling to fully disclose to others in the newsroom the truth about their humble ghetto beginnings and, instead, to possess the proclivity for putting on airs. To exist inconspicuously without calling attention to, or acknowledgement of, their race or race matters.

In truth, some simply, by their more “talented tenth” upbringing or social status acquisition by education, had more in common with our white colleagues than with a brother from the hood like myself who had attended a land grant university. However, America has taught me that there comes for many Black folk in America that moment of truth about being Black in America, despite any previously held delusions of insulation. Perhaps I am too harsh.

This much I know: At the Tribune and at none of the other mainstream newspapers where I worked, no one Black—or white, for that matter—ever offered to mentor me, to help shepherd my career. On occasion, an individual sister or brother did come to me under the shadow of secrecy to tell me about some disparaging or damnable thing some editor or reporter had said about me or my future at a particular newspaper. In most all of these cases, however, they failed to say what they had said in my defense or, more importantly, why that person had felt comfortable disclosing their animus or detracting assessment of me with them.

I cannot speak to why they did not speak up for me, defend me or come to my rescue. That is a question best posed to them. But I am grateful that my faith was never in them, but in Him—in God who had brought me safe thus far.

Beyond the newsrooms where I worked, the National Association of Black Journalists’ annual summer convention became my salvation. The NABJ convention was our space. A safe space. A place of rest, rejuvenation, regeneration and recalibration. A place where once as a young journalist, at a time when I was struggling to cope at the Trib, I was walking through the halls at a convention and happened to spot two Black journalistic icons, Acel Moore and Les Payne. They didn’t know me from a can of paint. I called out their names excitedly and walked up and introduced myself then popped a question after telling them I was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune.

“How y’all deal with these white folk?” I asked bluntly.

They asked me what I was doing at that moment. “Nothing,” I said. They promptly invited me to sit down and talk over a drink. I don’t recall exactly what those two battle-tested veteran brothers said to me. But I never forgot how they made me feel: seen, heard, encouraged... In that moment, they saved my career.

Early in my career, I came to believe that white newsrooms, much like much of corporate white America, prefer their Black men served spineless, speechless and sack-less and most preferably devoid of facial hair. That some Black journalists seeking to gain white capital within a news organization would very willingly flay Black reporters—behind closed doors or openly—to prove their worth and fealty at the expense of a fellow Black journalists' demise. There were undoubtedly those who wanted to protect their HNIC (Head Nigger In Charge) status. And those who were overcome with petty jealousy over someone more gifted and who, therefore, succumbed to the crabs-in-a-barrel syndrome that historically has at times made Black folk our own worst enemy.

I discovered that all skin folk ain’t kinfolk. That some Black journalists too played favorites and that if you weren’t in their elitist clique, you were left out in the cold.

That no matter how degreed or gifted we are as Black journalists, there will always be white journalists in newsrooms who believe we don’t deserve to be there. That fairness and equal opportunity for Black journalists is a game of cat and mouse.

That true friends in this business are few, but allies can be found.

And that having a network of support beyond journalism—to include mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, aunties, former professors and even the church’s faithful prayer warriors—can keep you grounded and encouraged through the storms of a career in journalism. Serve to remind you that eventually choosing to exit daily journalism stage left can be the bright beginning of a new act in the journey toward fulfilling the purpose God has placed within you.

My days at the Tribune taught me many lessons. Among the most critical: That everybody white was not my enemy and that everybody Black was not my friend.

That you can’t argue with excellence (words Tribune Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Ovie Carter had spoken once to encourage me).

That folk don’t have to like you in order to respect your work.

That you can mess around and lose your soul as a Black man—or woman—working for places and in spaces that were never meant for us. Or you can choose to stand firmly on what you believe about journalism. Choose to stand upon its principles and in your desire to make a difference—and seek to emerge ultimately from these institutions victorious, with your soul, mind and heart intact, refined by fires as a living testimony.

"The press has too long basked in a white world looking out of it, if at all, with white men's eyes and white perspective." -The Kerner Commission Report, 1968

On My Own

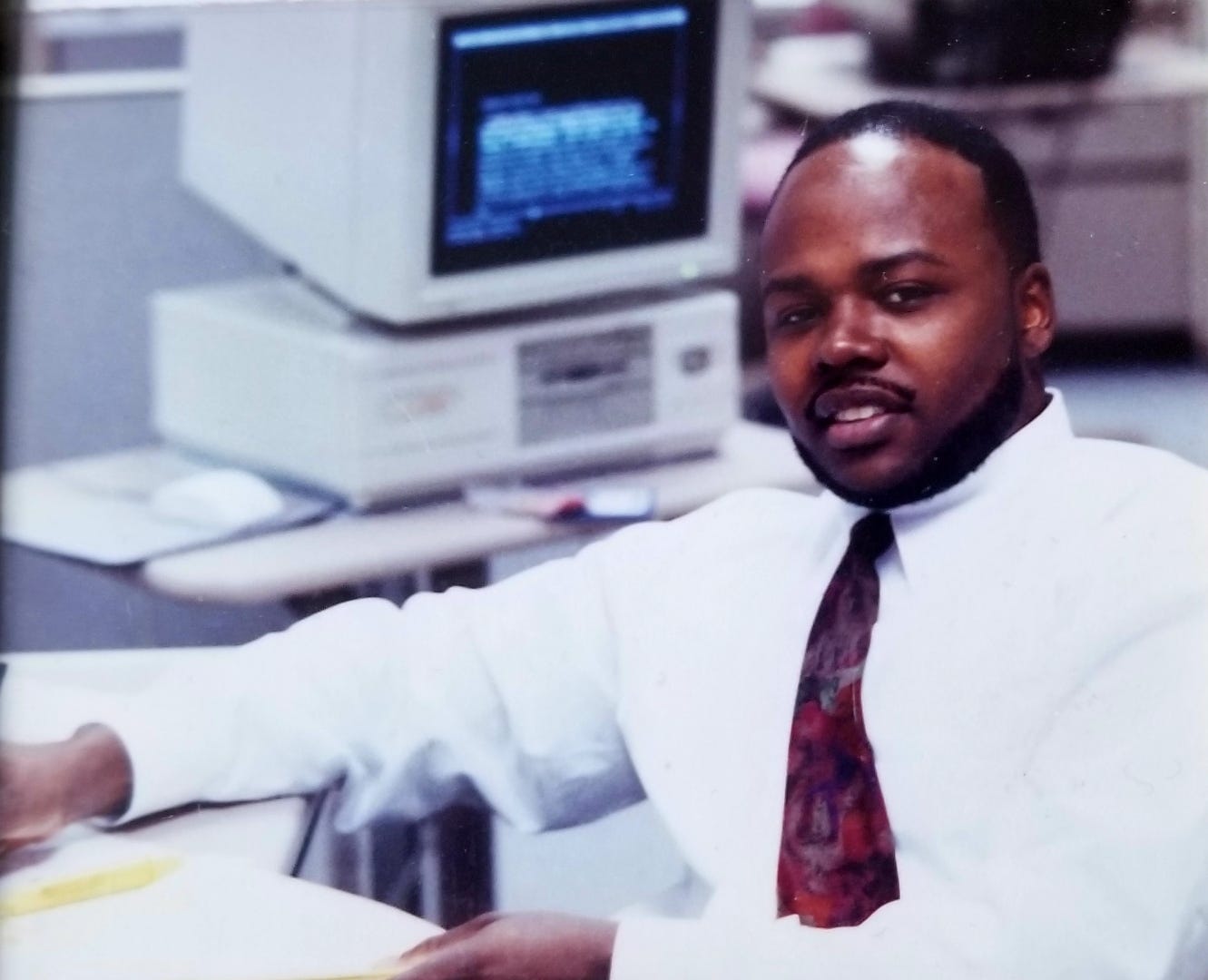

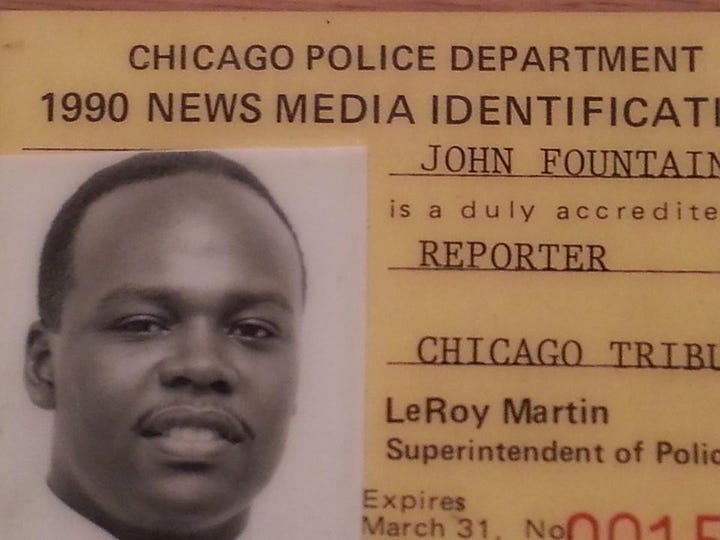

I WAS THE USUAL suspect. The typical police APB: Black man, dark-skinned, about 5’10” to 6 feet tall, 180-200 pounds, short hair or bald, big, possibly dangerous… I fit the description. And neither my four college degrees, my King’s English or my lily-white-collared shirt and tie shielded me. Not even my entry into the Tribune newsroom, made possible by my hard work and talent and my carefully self-constructed resume of a half-dozen internships and experience gained by hauling my wife and three young children across the country with me.

I was still just one of “them.” An outsider never to be truly accepted as an insider. Predestined to be forever side-eyed and deemed as less than, unproven or incompetent, and then required to prove myself competent again and again. Even when my talent and credentials outshined or outweighed my white colleagues’. Forever to be dubbed the “affirmative action hire” when the truth is that for white reporters their race affirmed their privilege and right to access the Tribune and other mainstream American newsrooms, sometimes lacking a college degree or journalism experience.

The color of their skin led white journalists—at least it was not a barrier—to promotion and opportunities and journalistic longevity. It ushered them ceremoniously down the pathway to becoming national and foreign correspondents, to executive editorial positions in this bastion of whiteness that reaffirmed the standard of whiteness that exists in the mainstream news media and that purposely diminishes and denies their own hand in the industry’s construction and perpetuation of newsrooms that remain largely bleached clean of Black journalists.

Not that many white journalists were not talented and deserving. There was simply no level playing field for Black journalists who were just as talented, qualified and just as deserving, if not more.

I watched over the course of my career young white reporters being spoon-fed breaking news stories and special projects, coddled, and given choice assignments and preferential treatment—clearly being groomed by “sponsors,” as we called them. Those sponsors were editors and senior reporters who looked like them and whom I have always suspected were reminded of their sons and daughters, nephews and nieces.

I did not despise this de facto internal legacy program. For most Black reporters, however, there was no such built-in system and few Black faces in position to chaperone young Black talent or hardly the same level of institutional commitment. In the words of Pattie LaBelle, I quickly realized I was “on my own.”

THE AMERICAN PRESS’ SO-CALLED commitment to goals of recruiting Blacks to the newsroom after the scathing 1968 Kerner Commission report—which found that fewer than 5 percent of the people employed by the news business in editorial jobs in the United States were “Negroes” and fewer than 1 percent of editors and supervisors—has proven, after nearly six decades, to be lackluster and mere window dressing. In fact, since the Kerner report, the percentage of Blacks reporting in U.S. newsrooms, according to the Pew Research Center is 6 percent, one point higher than it was more than five decades ago, although Blacks make up roughly 14 percent of the U.S. population. This is both a sin of commission and omission. Hardly happenstance.

Neither was my arrival at the doors of the Chicago Tribune, having extricated myself from the welfare rolls to return to college years after I had dropped out—first to Chicago’s Wilbur Wright junior college then ultimately a return to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, this time with a family. It was a journey inspired by the dream—and by purposeful and stubborn determination—to become a journalist.

By the dream of someday making a living and a difference in my hometown, where I grew up in deep unforgiving poverty on the other side of the tracks, the son of an alcoholic father who deserted us by the time I was 4, and who gave me his name and DNA but little else. I dreamed of shining the light on dark corners of American society, of being a voice for the voiceless, for the downtrodden and forgotten.

I walked into the majestic gothic Tribune Tower, at 435 N. Michigan Ave., a long shot from the impoverished Chicago West Side’s “Permanent Underclass,” who, a few years earlier, was a teenage father married by 19, with three children by age 22, and a welfare case soon after. As a licensed Pentecostal minister and former church deacon who had worked during my return to college as a bank janitor, as a food service worker at a hospital, as an unarmed security guard at a department store and various and sundry other jobs while earning my degrees, clinging to the dream called journalism, even when it seemed as elusive as a wisp of steam.

I entered that newsroom in fall 1989, at age 29, battle-hardened by the storms of life, in a sense, risen from the dead. Having defied the odds that were probably at least a million to one. Having scratched and scraped for seven years and given every scintilla of myself to try and become a better writer and reporter, committed to the one thing in life I loved more than God and family: Journalism.

I believed in journalism, drawn initially by my love for writing, which I had embraced since I was a child who discovered wonderment in the creative force of words unearthed from the soul and imagination and woven together. Writing has always been like breath for me. Life yielding. Essential. And the power to pen my thoughts and feelings, to share my stories and those of others from my world, through journalism in particular so that I—we—might be made visible, stoked my fire.

I dreamt of doing Pulitzer Prize-winning work—whether I ever won the coveted award or not. I dreamt of chronicling Black life with the sensitivity and insight of an insider’s eye and, by my contributions, lending a sense of balance to the overall journalistic portrait of life for Black folk in America.

I could have chosen another career. I had counted up the cost. And I chose journalism over and over and over again. And yet, the reality of what I found once I crossed the newsroom threshold as a full-time staff reporter kicked me in the teeth with near paralyzing ferocity. Of all the battles I had fought to get there, of all the barriers I had up until then overcome, none were greater than those I found inside America’s mainstream newsrooms.

Years later, after I had departed for the Washington Post and returned to the Trib for a visit, a Black male editor at the Tribune with whom I had worked during my time there remarked to me matter of factly, with detectable empathy: “Things I had only read about happening to Black men I saw happen to you here.”

I wasn’t exactly sure how to feel or what to say, or how to process his revelation. But the fact that he too was a Black man, albeit light-skinned with a higher-pitched voice, much smaller in stature and with a more affable disposition—the sum of which made him more palatable to white folk and much less threatening than the stereotypical Black American menace embodied in John Fountain—left me numb.

And yet, his words provided some sense of clarity and affirmation amid the swirling, maddening sea of self-doubt and angst in mainstream newsrooms as a Black male reporter and in which I sometimes felt like I was hopelessly drowning. I am still grateful for Reginald Davis’ words and honesty, and grateful for those early hardships and fire baptism into reporting while Black.

The Shining

AS I SAT AT my desk inside my cubicle in the newsroom one day that fall in 1989, I could plainly see through the glass office, the head of another Black man bobbing up and down—up and down. The frail, dark-skinned elderly gentleman was doing something strange to me. At least I could not easily discern from my vantage point in a cushy chair that yielded only a partial view into Squires' office.

“What in the hell could this gray-haired Black man be doing in there?” I wondered silently.

Finally, I could not resist any longer. I stood up to see. There it was in plain view: The white editor's feet were propped up all cozy-like as he leaned back in his swivel chair, talking on the telephone while the wiry little Black man, dressed in a blue custodial uniform, buffed out a shine.

To my surprise, no one else in the newsroom seemed interested or unusually stricken by the sight of this activity. “Al the Shoeshine Man,” as he was known, would meander through the newsroom, offering reporters and editors a shine right where they sat. His real name was Albert Voney, described in a 1989 Chicago Reader story as “a wiry, toothless, 57-year-old south-sider.” He would kneel there in newsroom offices or cubicles, between desks and the makeshift waist-high wall near the tin trash bucket, down on the carpeted floor. Al came around a couple times a week.

A Tribune shoeshine man by one name or another had been doing so before my time and was as much a fixture as the Polish and the Black cleaning women who wore purplish-blue smocks and showed up every night to clean the bathrooms, empty the trash and wipe off our desks.

In time, I got to see Al at work many times, dropping to his knees and shining reporters' shoes as they hammered away on stories, a scene that blended into the cacophony of chatter, ringing phones and fingers pecking keyboards at deadline in the bustling newsroom. There were a few Black women who gave Al their shoes to shine outside the newsroom. But Al's clients were typically white reporters and other white Tribune editors.

The sight of Al the Shoeshine Man doing his business disturbed me, although I never complained to management or to my editors, or to anyone, except to some of my Black colleagues. What disturbed me was not so much that Al was shining shoes for a living. It is an honest living, and I always figured a man's legal trade to be his own business.

What disturbed me was seeing Al on his knees time and time again, shinning white men's shoes, and the image of subservience it conjured. The kind of menial jobs that Black men were once relegated to perform at white men's pleasure. Maybe it wouldn't have been so bad had they set him up at a stand somewhere in the spacious tower, which would have made it seem more respectable—with his patrons sitting in chairs and Al simply bending to shine, instead of on his knees beneath them.

It was, by this time, 23 years after the Tribune hired Joseph Boyce, its first Black staff reporter covering Metro news. Boyce was preceded by Vincent Lushington “Roi” Ottley, another Black writer who, in 1953, began writing a Sunday column for the Tribune. During a telephone interview many years ago, Boyce told me that he himself was the first Black journalist allowed in the Tribune’s newsroom. Ottley, a decorated writer and journalism pioneer, Boyce said, had to drop his column off at the guard desk.

Boyce told me that on the day he arrived he and an editor were walking through the newsroom so that he could be introduced to another editor. Standing next to that editor, to his surprise, was another Black man who gave him the silent brotherly nod and smile as their eyes met. That other Black man was the resident shoeshine boy. And it was clear to the new Black reporter that Black men were certainly already welcome in the newsroom. And that whites were comfortable seeing us there, just not as reporters but as shoeshine boys.

MY ARRIVAL AT THE Trib came fresh out of graduate school and on the heels of five newspaper internships and work at two student newspapers. It had been five years since Tribune journalist and gifted commentator Leanita McClain, whose book, “A Foot in Each World,” I had read in college, committed suicide. Her internal turmoil over race within the newsroom is something I would come to experience firsthand, even while narrowly eluding Leanita’s self-inflicted fate as my troubles at the Trib—compounded my own personal woes—sent me barreling down the abyss into a deep depression.

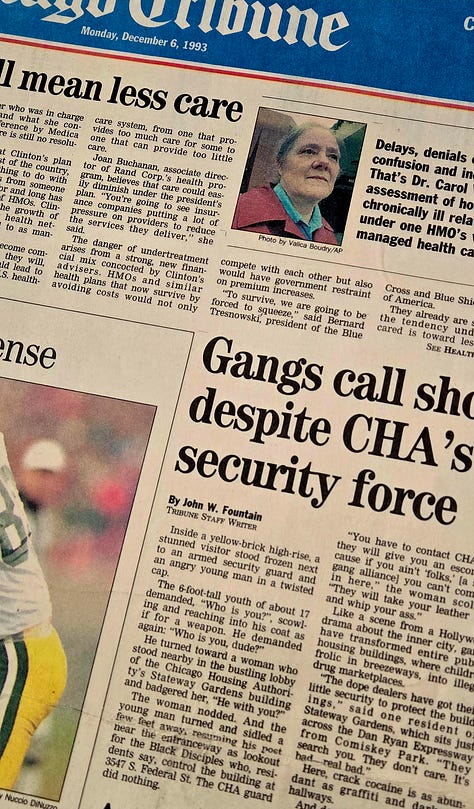

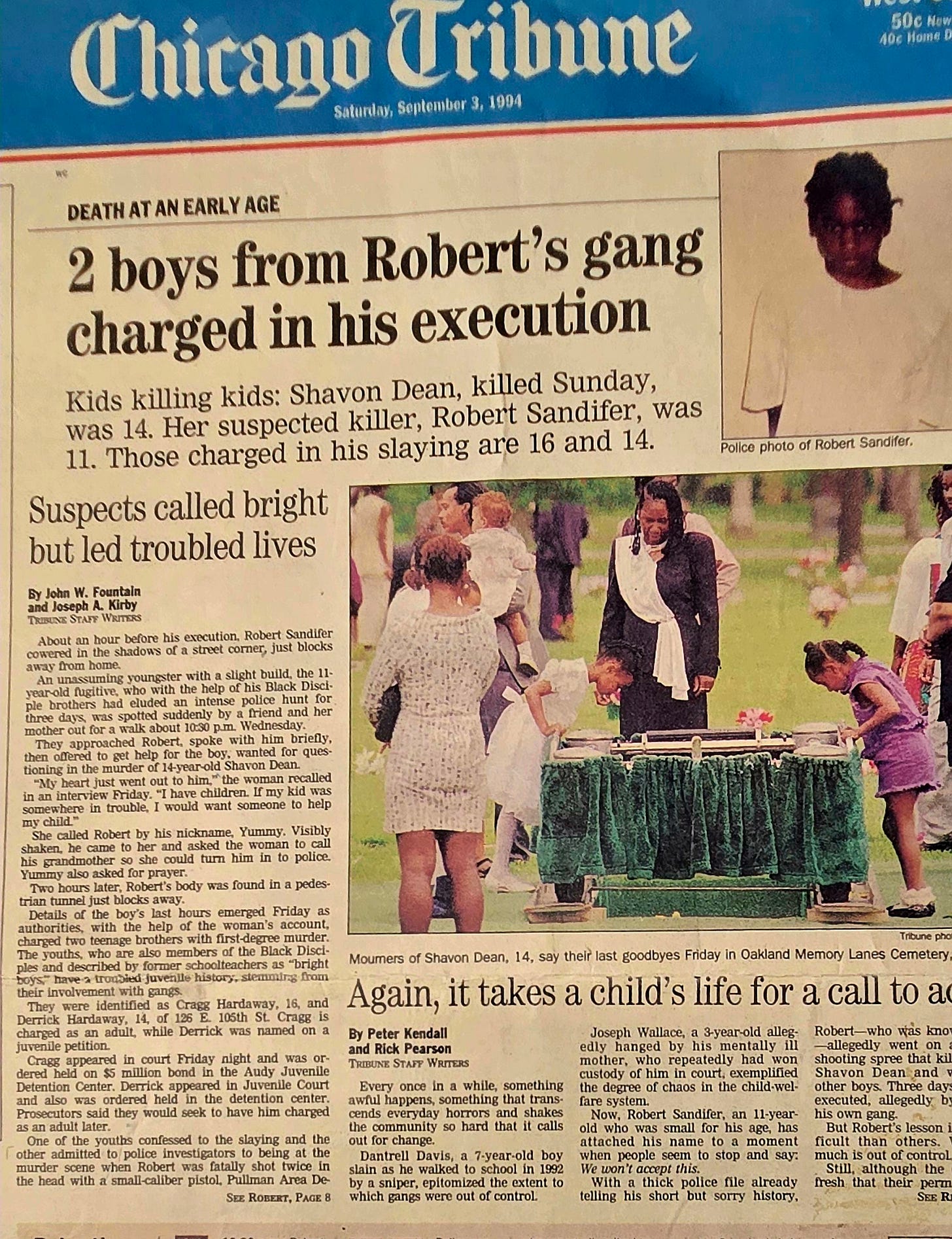

Back then, murder, especially the murder of poor Black folk, even innocent children, had not previously been on the Trib’s agenda to any large degree. As a young reporter, I found out the hard way. The subjects of homicide, inner-city violence, poverty, urban neglect and social justice were my focus since arriving.

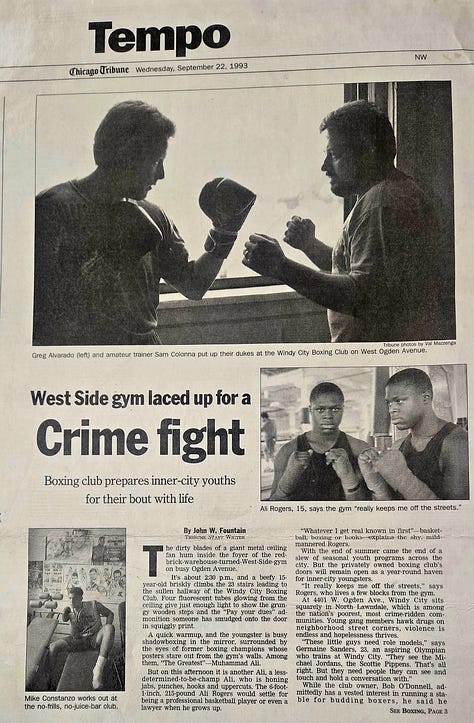

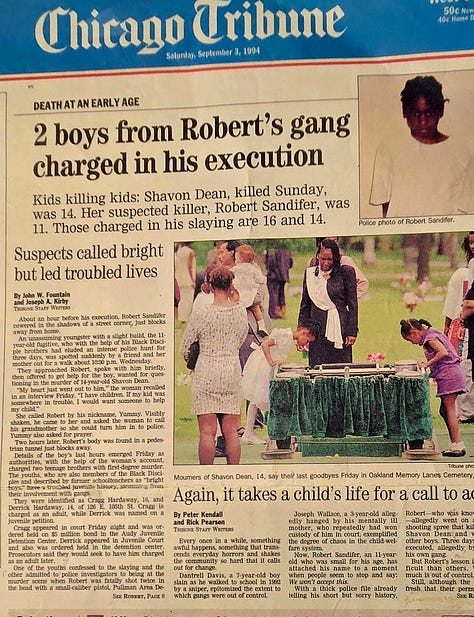

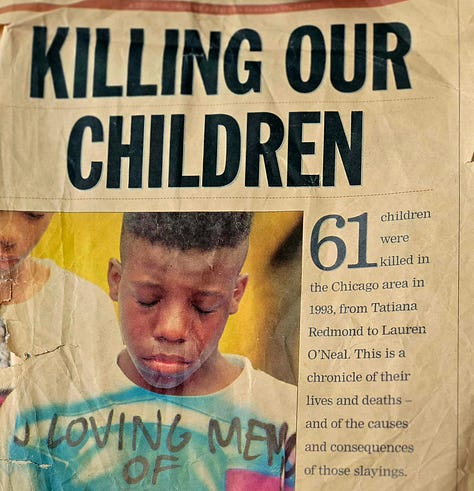

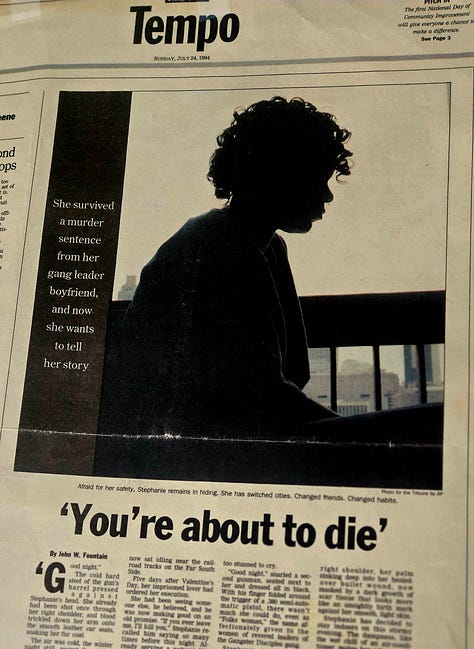

In 1993, the Tribune embarked on “Killing Our Children” project, a noble series in which the newspaper set out to chronicle the life of every child 14 and under slain that year, most of them Black. The majority of those stories were written by white reporters with most Black reporters on the staff blacked out of that coverage—a point I remember making later at the larger Metro diversity powwow. I had written a couple of stories for the series upon my return to the staff after a nearly year’s leave of absence to live in England.

As the “Killing Our Children” series’ potential Pulitzer buzz grew inside the newsroom, reporters who would have previously shunned those stories suddenly had an affinity for them. I quietly hoped we would not win a Pulitzer, mostly because I despised the hypocrisy and the push for a prize more than a commitment to change. My sense was that the series did little to alter the way the newspaper covered or saw Black life. In fact, I had by then simply come to accept that some of my colleagues couldn’t even see me beyond an image that was the worst of their perceptions about Black men as menaces to society and America’s most depraved, most dangerous.

And yet, there I was, in the flesh, a son of the “American Millstone,” the antithesis of the Trib’s indictment in 1985 of Chicago’s West Side Black ghetto poor whom it concluded were the “Permanent Underclass,” devoid of middle-class values, a societal albatross who would never amount to anything. I sat in the newsroom among them, educated, minted and well qualified. Except to some of my colleagues, I was, in the words of Leanita McClain, “The Black. Just another nigger.” Albeit in my case a Black male journalist—to be feared, even in my silence.

Still, Barb was not my enemy. And I was not so much angry as I was deeply hurt, confused and offended. I was one-dimensional in her eyes, the shadowy scary stereotypical image that is potentially assigned to every Black man in America. She did not see me as a loving father, as another woman’s son, as a Pentecostal church boy, loving brother, nephew and grandson. As a Black man who never spent a day of his life in jail.

Not as the kid raised in the church who grew up with middle-class values despite our poverty, and who had attended Catholic high school. The former Boy Scout, Sunday School teacher, college graduate. I was, by her own admission, even in my suit and tie and spit-shined shoes and my acquired middle-class certifications—among them having become a reporter in the very newsroom where she was an editor—still someone to fear. Damn.

Many years later, I have reflected on my meeting with Barb that day after the Metro diversity discussion, still shaking my head at how my silence and the words, “Never Internalize Their Disrespect” could strike fear in her heart. The offending sign was my salvation, like some Bible scriptures (Psalm 75:6-7) that I printed out and kept in clear view in my workspace as part of my armor as I sought to gird myself and remain steadfast in my heart’s desire to be an American journalist notwithstanding the skin I am in as a Black man.

Those words helped save my life and sustain my career in journalism, where my greatest sin was reporting while Black. Black Black. Ghetto Black. A non-comical Black man with dark skin and unmistakable, undeniable African features. A serious, Black man, sometimes perceived as surly, quiet, with brown-eyes and coarse hair. Irrefutably, undeniably Black. And blacker than I had ever realized until entering white America’s newsrooms.

I still appreciate Barb’s honesty and her humaneness, the courage it must have taken for her to say what I suspect some other white colleagues at the Trib felt or thought about me and which was perhaps, in some cases, even worse. Some have suggested that I am too kind or gracious in my judgment of her, or lack thereof. That Barb was, in a word, “racist.” I cannot say what was in her heart. Only what I saw in her eyes as she sat courageously across from me to share her truth.

Better, Not Bitter

AFTER ALL THESE YEARS, I am convinced that not much has changed in mainstream American newsrooms for many Black reporters whose only sin is reporting while Black. I am only partly heartened by the push to “reimagine journalism,” being led by initiatives like Press Forward, by a mix of small start-up nonprofit digital newsrooms with a community focus and some among the legacy press that have converted to a non-profit model and also created media partnerships as a simple matter of sustainability.

But if the same old heads—white and Black—are the gatekeepers to the kind of journalism that gets produced—both in quality and diversity—and to the kind of journalists who get hired, as well as which organizations get financed, then eventually we will be left with the reinvention of what currently exists. Will they fund so-called malcontent Negroes, dissonant and diverse chords, those square pegs or new voices with greatly needed perspectives and the audacity to still believe in the power and purpose of journalism? I can’t say.

What I do know, however, is that life and my journey have taught me that for as long as there is breath and words and heart and purpose, good journalism will find its way. I am reminded even now that for Ida B. Wells and Frederick Douglass, journalism was always about the power of the pen, about truth, and the social uplift of our people. Not awards. Not celebrity.

The telling of my story will undoubtedly draw dismissive naysayers likely to assert that what I have written here are the ramblings of a bitter man, sour grapes. My retort is that after all I have endured in journalism, harboring bitterness might indeed be justifiable. Except there is only one letter difference between “bitter” and “better.” Long ago, I chose better and sweet nectar of success.

I ain’t bitter, baby, I’m better. So much better now. To God be glory.

I trust that my steady rise in journalism, from the Tribune, even to the national newspaper of record, my return to my alma mater years later as a tenured full professor, a more than 35-year record of writings that have been consumed globally, and the truth that some of my former students are now doing good journalism across this nation, will speak for me. As well as those whose lives my pen and journalism passion have impacted. And most importantly, my God, who is my judge and redeemer.

This much I can also say: I never quit to opt for an easier road, like some of those who will cast aspersions. They didn’t break me. The journalism flame still burns deep in my soul. In the words of rapper DJ Khaled, I went “all the way up.” I won. And sharing my true story of how I made it over is my true testimony.

I wish that I did not have this story to tell. I wish that it was not my testimony that as a Black man in mainstream American newsrooms I faced the searing triune fires of discrimination, racism and inequality, and downright unfairness and ugliness for what was so clearly the sin of the color of my skin. But I lived it. I have a right to tell it. I must tell it.

So, exactly 35 years since that December I was hired at the Tribune as a full-time staff writer—officially launching my professional journalism journey—I now write. In hopes that my words will be lifeblood for others who follow. I write as a chronicle of one Black journalist’s journey through the fires of the mainstream American press that have consumed far too many like me. Especially for those who find themselves standing alone in some newsroom and in the company of more critics than advocates, I write.

And finally, I write as proof—in the words written by Stanley Crouch and profoundly delivered by Rev. Jeremiah Wright in Wynton Marsalis’ “Premature Autopsies”—that dragons can be defeated.

And still I—we—rise.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com

John W. Fountain is a tenured full professor of journalism at Roosevelt University. A Chicago native son and multi-award-winning journalist over a more than 35-year career, he is formerly a national correspondent at The New York Times, staff writer at both the Washington Post and Chicago Tribune, and most recently a columnist for 13 years at the Chicago Sun-Times. He is author of five books, including his memoir, "True Vine: A Young Black Man's Journey of Faith, Hope and Clarity."

His forthcoming second memoir, to be released in summer 2025, is titled, "50 Cent A Word: Diary of A Freed Black Journalist." The book chronicles Fountain’s journey from a Chicago Black boy who grew up in one of America's most impoverished neighborhoods to become a Black journalist at his hometown big-city daily newspaper and later to matriculate to some of the nation's most storied newsrooms.

His is a true story of faith and hard work. A story of struggle, tears and hardship, and of coming face to face with the unrelenting current of racism and classism that still permeate mainstream American newsrooms today. This more than 50 years since the Kerner Commission chastised the news media in its scathing 1968 report for perpetuating the nation's volatile racial divide by its intentional lack of Black reporters and editors, which lay at the root of its biased and racially jaded platter of daily American journalism.

At its core, 50 Cent A Word is a love story. The story of one man’s love for journalism. A story of his unfettered faith in the power of the pen and his desire through journalistic storytelling about the human condition to make a difference.

This book is ultimately one man's story of triumph. A clarion call for much-needed change within one of America’s most fundamental institutions: The American Press.

Fountain’s story is a testament of perseverance and dedication to the ideal of journalism. It is a testimony that shines forth with hope and lessons for a new generation of Black journalists and perhaps for an industry whose core credibility hinges on its ability to present a fairer, more accurate portrait of life in America for all of her citizens. It is a story we can all share.

Awesome article. I'm getting what Don said framed. “Never internalize their disrespect.”