Journey To My Alma Mater: In Search Of Solace, Memories and Marrow

The contents of my professor's "papers" are an assortment of scentless inanimate letters, yellowing and faded newspaper clippings, hand-written notes… I search for something among them.

By John W. Fountain

CHAMPAIGN, Illinois, Dec. 15—INSIDE THESE HUSHED ARCHIVES of the University of Illinois on a sleepy end-of-fall-semester Friday afternoon, a librarian escorts me to a black cart topped with seven boxes that contain the papers of my professor and mentor.

The contents are an assortment of scentless inanimate letters, yellowing and faded newspaper clippings, hand-written notes… I search for something among them. Exactly what, I do not know for certain. But I am drawn by forces I cannot fully comprehend or articulate.

Whatever those forces, they have pulled me like gravity to 408 W. Gregory Dr., to a fluorescent-lit room that houses the University Archives.

Some years ago, I remember stumbling one day upon the existence of this collection while doing a Google search on: Professor “Bob” Reid—and University of Illinois. To my surprise, a record of his “papers” turned up. I decided that someday I needed to visit the university’s Main Library to review them. Someday…

Except reviewing the notes, former possessions and words of departed loved ones, even of a beloved professor, is not an unemotional or painless proposition. It requires, for me at least, a certain willingness to accept the joy and also the salted tears that may come along with unearthing sweet memories and also the stinging reality that they are forever gone. Even if some archived remnants of days and times past might temporarily be held between my fingers.

Perhaps such a search can lead to the discovery of more answers than questions. Perhaps to more purpose than pain. Perhaps to the recollection of some life-yielding, faith-building intangibles that once grounded us and that we somehow lost somewhere between yesterday and today, but which may again, if found, prove sustaining for the pursuit of future mountains and dreams. Perhaps.

Or maybe the find is less lofty, though no less meaningful, and the journey essential to the soul.

Box No. 7

A STUDENT’S RECENT NOTE at the end of this fall’s semester at Roosevelt University, where I am a professor of journalism, kindled memories of my struggles as an undergrad. Back then, I was married with children, having been born and bred in poverty on Chicago’s West Side into the nation’s “permanent underclass.” Or as Harvard University sociologist William Julius Wilson described us: “The Truly Disadvantaged.”

Either way, I was facing a daunting uphill battle that was, in hindsight, even more dire and improbable than I could ever have imagined or might have been willing to admit at the time.

“I wouldn’t be here without you. Did you know that?” my student, Kay, wrote in part on a Christmas card she to handed to me on the last day of class, and which I promptly tucked inside my suit jacket pocket to read alone later.

“I don’t want to cry in front of you,” I remarked with a smile and chuckle, anticipating a sentimental note, which I have sometimes received from students over my 20 years teaching.

Truth is, I wouldn’t be here without Professor Reid. Not in journalism. Not in a university classroom.

I’ve long admitted that. And I have long understood that miracles are most often wrought by human hands and hearts. By words of hope and inspiration from those who have the ability to see you through the prism of possibility, even when you feel broken, irreparably damaged or inconsolably battered by debilitating storms that can steal pieces of the soul. Prof. Reid always saw me beyond my poverty, beyond my socioeconomic DNA, beyond my race—even when I could not.

After reading Kay’s note that evening, I contacted the Graduate Library at Illinois:

“To Whom It May Concern, My name is John Fountain. I am a graduate of the University of Illinois and a former student of Prof. Reid's. In fact, he was my mentor. I would like to review his papers, including ‘restricted’ files concerning letters of recommendation, papers and other materials concerning me in addition to Prof. Reid's papers in general. Please advise…”

Their usual response time is within two weeks, a library administrator said upon replying. A few days later, however, another message popped into my email inbox. Prof. Reid’s papers were ready for my perusal. I gassed up my car and headed to Champaign, my heart and wheels racing.

Inside Room 146, I place my cell phone and Mac Book on a varnished wooden table and pull from the adjacent cart the top box, marked “Box 7.” It is rectangular and gray and inscribed: “University Archives, Communications, Journalism, Robert D. Reid Papers, 1978-2003, Articles Authored By Former Students”

Inasmuch as I feel led here, I stand before these boxes of time and memories, myself strangely a box of nerves.

“I often think back to our discussions at Greg Hall… School was very difficult for me at that time, particularly with the pressures of taking care of a family. There were many many times when I wondered whether or not I had what it took to make it as a journalist. In those times when I needed encouragement, I found it in your reassurances and in your care for me as a human being. I felt like you cared and that you believed in me.” –Letter from Prof. Bob Reid’s papers, dated Thursday, May 6, 1999, and written by John Fountain, sent from fountainj@washpost.com

Letters

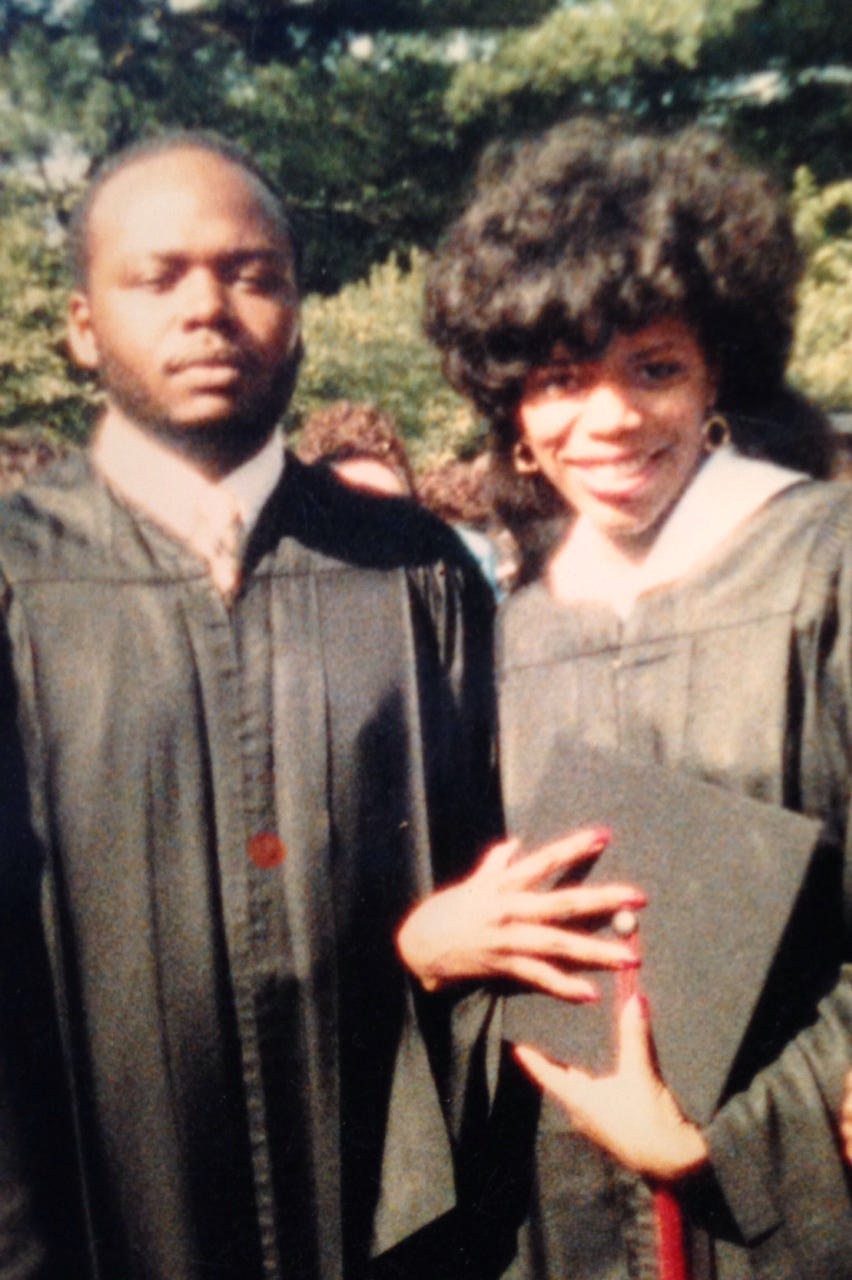

I ARRIVE BACK AT Illinois’ campus exactly 19 years since Professor Reid retired. About four months after I assumed my post here as a new professor, Reid died at his home in Champaign after suffering a heart attack.

At my return to campus today on this nearly 60-degree sunny December afternoon, it has been 19 years since that fall of 2004 when I became a tenured full professor of journalism at Illinois with Prof. Reid’s blessing and recommendation after a career as a newspaper journalist. Nineteen years since I received news—after I had arrived home in Chicago’s south suburbs from teaching in Champaign that week—that 10 days before Christmas Prof. Reid was gone.

Four months earlier, I had moved into Professor Reid’s old garden-level office at 23 Gregory Hall—freshly painted white cinderblock walls, his books that I had earlier selected to keep, lining the metal shelves. It was a full circle moment: mentee following in the steps of his mentor, returning to my alma mater in the same office where I had spent countless hours as an undergrad and also graduate student, absorbing the counsel and wisdom of a professor whom I came to call my journalism father.

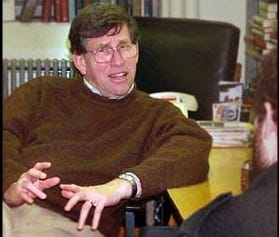

We were perhaps an unlikely pair. He was white. I am black. He was bold. I was shy. He earned degrees from Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. Here I was at Illinois on a second chance and barely. I had dropped out of college a few years earlier and was, by age 22, married with three children and on welfare.

Reid was a tall and bespectacled man with a schoolboy smile who also possessed the demeanor of a drill sergeant. He had reddish brown hair that even in his 60s seemed as thick as Clark Kent’s. His husky baritone voice and guttural laugh flooded a room, spilling into the halls. He was tough but fair in his courses. None of them was more feared than Journalism 380, the capstone undergraduate reporting class in which students were required to produce a project series.

Prof. Reid was strict. Work turned in even a minute late was not accepted. Reid’s rule was simple: Once he closed his door at the start of class, anyone outside that door was late. Some students learned the hard way. I have seen grown men cry.

Reid was a stickler for Associated Press Style and grammar. Keen on detail. But mostly, he was a torchbearer for journalism and its foundational principles, an advocate for humanity and public affairs journalism and for the ability of journalists with passion and a sense of purpose to make a difference. Most importantly, he believed in students and in taking the time beyond the classroom to stoke our fire and dreams.

“You can’t teach fire in the belly,” he used to say with the glint of a preacher in his eyes, his voice unwavering. “You’ve got to have your own.”

Reid was like fire—hot, irrepressible, contagious. Like many other students who sought his wisdom and advice, I spent countless hours collectively in Prof. Reid’s office in what I later called our “fireside chats.” The sun had sometimes set by the time we ended.

Or sometimes Prof. Reid would stroll outside to smoke a cigarette. He puffed and exhaled with the same relaxing and deeply satisfying pleasure I had witnessed of my mother, a lifelong smoker. Prof. Reid seemed to smoke with almost the same passion with which he taught, at least the same commitment. No judgement. Just the facts.

I trusted Prof. Reid. My trust and respect for him were earned by the way he always spoke to me: respectfully, eye to eye, and without animus, gruffness or rudeness, or as if I was the “Black student” in class who clearly didn’t deserve to be at the university in the first place. That was what I experienced at times from a few other university professors.

I vividly remember a journalism professor barking at me angrily once as if deeply bothered by a question I had asked during class. His response left me feeling embarrassed and stupid, holding back tears, and wishing I could crawl underneath my desk.

That professor who was white, like every other professor during my entire undergraduate and graduate study—with the exception of a female African-American political science professor—then turned to a white male classmate and in the next breath praised him with the sweet adulation of a father to a favorite son. Prof. Reid had a way of making unfavored sons feel at home.

During our conversations in graduate school and afterwards, he sometimes expressed his concern that guys like him and me, as he put it, would someday be less palatable as students to the University of Illinois. He explained that he sensed among administrators and other powers that be a desire to make the student body more homogenous—white, and middle to upper class. He worried about what he said was a push to raise the average incoming student’s ACT and SAT scores to help boost the school’s ranking and prestige, and the desire to gain more students with coffers.

Prof. Reid also often spoke about the state of diversity in American newsrooms, or the lack thereof. About the need for reporters at daily newspapers who were Black like me, having matriculated from the school of poverty and hard knocks—and who would not leave their experience and perspectives on the curbside of American journalism. Black journalists who might stand principled and unwavering. In his mind, there was clearly a need for a new generation of journalists not from the usual cookie cutter mode and whom he deemed were essential to journalism’s survival.

Mostly, I did more listening than talking. And mostly, Reid talked about journalism and life. But I have never forgotten his ominous warning about the university we both loved, even if I had over the years forgotten some of the specifics of his praise and his own hopes for my journalism journey.

“U of I Journ

B.S. & M.S. degrees—

now New York Times correspondent

formerly Washington Post and Chicago Tribune reporter

–A note handwritten in cursive appears below a printout of a summary of my book, “True Vine: A Young Black Man’s Journey of Faith, Hope & Clarity”

Revelations

INSIDE PROF. REID’S BOXES, I find a treasure trove of the stories by former Illinois journalism students whose work he used to cut out of newspapers or else print to hang like precious jewels on the bulletin boards outside his office as inspiration to current students. I recognize some of the names: Laurie Goering, Ismail Turay Jr., Dawn Turner Trice, Peter Kendall… John W. Fountain.

One by one, I pull the boxes, carefully open the folders, and turn the pages gingerly, eavesdropping on conversations and searching in earnest for something that will, in particular, speak to me, though I do not know what I need to hear. Inside “Box 7,” I had already discovered more than a half dozen of my news stories. Rekindling memories of Prof. Reid’s pride in us, they wash over me like an ocean wave over golden sands at a summer’s sunrise.

I search on, flipping through file folders, in a box marked, “…Letters From Former Students.” My eyes settle upon letters from alumni writing to update Prof. Reid on their career, some of them seeking advice, and many expressing gratitude for his (TLC) teaching, love and care. I find one, written by a former student then a reporter at the Washington Post.

“One of the most vivid conversations I remember is that you said to me, ‘John, someday you’ll be this successful journalist and you’ll come back here to speak. I won’t care about what kind of car you’re driving…

“What I’ll care about is what kind of person you are. And when you pick up the telephone at work one day and there’s some kid on the other end saying, ‘Bob Reid at the University of Illinois told me to give you a call,’ that you take the time to talk to them. My answer is still ‘anytime.’ Anytime.” –Letter to Prof. Reid, May 6, 1999, from John Fountain

I had forgotten I wrote that letter in between the now fuzzy phone conversations and other messages exchanged between professor and former student over a decade since I had left Illinois. But I had not forgotten over the years to keep that promise.

In my search of Prof. Reid’s papers, I discover more letters. Among them letters of recommendation. They are medicinal in their reaffirmation, even if causing my years of uncertainty and fear about life and the possibility of building a career in journalism to resurface with painful precision.

“I have known John and his work intimately since he was an undergraduate here. He was clearly very bright and had special insights even then, but his writing skills and basic education lagged behind those of fellow students from more well-financed suburban schools,” Prof. Reid wrote on my behalf to the Michigan Journalism Fellowship—a highly selective program for mid-career journalists in the U.S. and abroad.

“We worked with him hard and gave him a lot of extra help, but we kept the expectations and standards high. He responded extraordinarily well. At both the Chicago Tribune and Washington Post, he did able general assignment work but went beyond that to do some truly compelling vivid journalism in imaginative ways and that underlined the human dimensions and consequences of urban life for low-income minorities… John embodies what ASNE says it wants and what schools like ours have tried to cultivate.” –Letter from Prof. Reid to the Michigan Journalism Fellows program, Feb. 1, 1999.

As I read, my brown eyes swell with tears that I have to fight hard to keep from rolling down my face. Not for pain. But for the joy of a professor who could always see me, even when I could not see myself.

I discover one more letter, printed from Prof. Reid’s email. It is one of the last he ever wrote concerning me. It was prompted by an email in 2003 from Loren Ghiglione, then head of the Medill School of Journalism.

“Dear Prof. Reid, I have met John and read his powerful book. He has applied for a teaching position at Medill. Medill likes to think it sets high standards for writing, reporting and editing. …Medill students are bright, demanding and sometimes impatient How do you think John would deal with them? John listed you as a reference.”

Prof. Reid writes back: “…If you had been present at the creation of John Fountain the journalist, as I was, you would realize how enormous the odds were against his having accomplished what he has. Those odds were on the order of a million to one, very conservatively estimated. If anything, John’s book underestimates the obstacles he had to overcome and is too modest about how monumental were his efforts to make himself into what he has become.

…Indeed I have told him that it is my hope that he would succeed me here at doing what I have done for nearly 25 years, not because I thought he would be a clone of me but because of my confidence in his character, his passion, his imagination and his dedication to journalism and the next generation of journalists and civic leaders.

“…He will not always make things easy for either his students or his bosses in the University, but he will make a great contribution to the future of journalism, to the larger society and to the planet… You should hire him before someone else does.”

His words are clouded by my tears.

Full Circle

I WALK OUT OF the Graduate Library, having used my Android to snap photos of letters and newspaper clippings. Then, once done, I had placed every item meticulously back into its designated box. I stand now on the library’s steps in the warm evening winter air. An occasional student wearing a commencement robe passes by. I feel a mix of emotions. I am also pensive. I decide to visit our old haunt, Gregory Hall, just a stone’s throw from the library.

I enter the doors and into the main hall, where, to my right, the office of the College of Communications is now the office for the College of Media. It was in this office where, upon my first visit as a student sometime in 1984, I encountered Dean William W. Alfeld, a chipper dapper older gentleman.

“What do you want to major in, broadcast or print journalism?” he quipped back then, our conversation still resonant after all these years.

“Broadcast,” I replied.

“Anybody can read the news,” he said with a chuckle and wry smile. “Why don’t you do print and learn how to write, get a skill you can use?”

“OK,” I said. “Print.” It proved to be priceless advice for a lifetime.

…To my left is a wing of the hallway leading to the College of Communications library, just past the journalism department office. Even here are memories of Prof. Reid and of a past letter that I did not find in his papers. I was walking through that hall one day as a graduate student when he asked me if I had a moment. I said, “Yes, of course.”

“What I’m about to show you I could probably lose my job over,” he said before handing me a typewritten letter. “But I think you need to see this.”

My eyes fell upon the paper. It was a “letter of recommendation” I had asked my former supervisor at the Champaign News-Gazette newspaper to write on my behalf for admission to graduate school. My heart dropped as I read his words, most of which I cannot recall with specificity, although its spirit and intent are forever ingrained. I had asked him for a letter of recommendation. He wrote that I should not be admitted to graduate school.

“Not everyone means you well, not everyone can be trusted,” Prof. Reid consoled that day, as I handed the letter back to him. “If (he) could not in good conscience write a letter of recommendation as you had asked, he should have declined or at least have been honest with you about his thoughts.”

That newspaper editor’s words and betrayal stung. I aways suspected the underlying issue was racism. That it had more to do with the fact that I am Black and that the editor, who is white, meant me no good.

Prof. Reid’s revelation would dictate many years later my policy on writing letters of recommendation for students and others: to choose honesty and openness over dishonesty and cowardice; to always provide them with a copy of the letter; and to decline if I am unable to offer a recommendation.

It still puzzles me why my former editor, if only for the sake of human decency, did not choose a different course of action. But of this I am certain: That despite him, I went on to earn my master’s degree from the very program he had deemed me inept for. That I then went on from there to a successful journalism career at some of the most storied newsrooms in America, and ultimately returned to that program as a tenured full professor. And finally this: That I have had a career he could only dream about. Of this I am damn certain.

I descend the stairs to the basement. It is the end of the semester, the building quiet and nearly empty. My name—and Prof. Reid’s—are long gone from Room 23, and since replaced by someone’s I do not recognize. I left Illinois in 2007, three years after Prof. Reid died, to teach at Roosevelt, listening to my heart and desire to teach in my hometown.

I linger a short while inside Greg Hall for old time’s sake, then inhale deeply, as if by doing so I might ingest for one last time a season and place that have become distant memories. I walk out of Greg Hall still uncertain of why I had felt compelled to make the 100-mile drive from my home in the south suburbs of Chicago to this campus that I fell in love with during my sophomore year in high school when my team attended Lou Henson’s Fighting Illini Basketball Camp.

Before making this trip, I had inquired several times of others close to me whether they thought my desire to look at Prof. Reid’s papers sounded wacky or morbid. They said, “No.” But they had no answers.

There were none as I drove north on Interstate 57 back toward home. And there were no answers or clarity until days later as I began to sift through the circumstances and feelings sparked by my student’s Christmas card and note.

Kay wrote: “I wouldn’t be here without you. Did you know that? When I lost my voice, I’d lost everything. My sense of hope, of reason, of anything that made me feel like I would make a difference. But there you were, always giving me enough to keep me from giving up. You were savior in a smart suit and wearing wisdom like a pin. You’ve changed me forever. I will never again be the person I was before we met. I have more to thank you for than could ever fit on all the paper in the world. So I’ll leave it at this: Thank you, for never letting me choose silence.”

I could say the same about Prof. Reid. Except he was savior in a sweater and glasses.

After reading Kay’s note, I responded with a letter sent by email:

“Dear Kay, Thank you so very much for the card and your heartfelt note. It moves me to know that as a professor, as a human being, I have made a difference in your life. It’s more than X’s and O’s, so to speak for me as a professor. It always has been. I approached journalism the same way as a reporter.

Some years ago, exactly 19, my mentor at the University of Illinois, Professor Bob Reid commended me for my success as a journalist then said that the next half of my life and career would define my legacy. He said he hoped that I would choose teaching and that I would teach at the University of Illinois.

I could have told her that in preparing for my journey as a journalist I could not have had a greater mentor. That in all of his instruction, counsel and wisdom, he never tried to change me, only to help equip me for the road ahead. That it was as if Prof. Reid had been hand-picked for me and that our paths were destined to intersect. That all along my professional road I encountered opposition, racist venom, lies and innuendo as a Black journalist, unfair treatment, discouragement and impediments to promotion. And that was just inside the newsroom.

I could have told her that I only ever had one mentor: Prof. Reid. And that each time, over the course of my career when I felt despondent as a journalist, discouraged, defeated and like throwing in the towel, it was remembrance of Reid’s words and his faith in me that lifted me. They lift me even now.

I wrote: “…Kay, you have reminded me more than ever to grasp the reins of life and to seize every moment—to live, laugh and love. You have reminded me of the importance of this gift called writing—meant not just for ourselves but for the good and uplift of others. You have reminded me that we are all on the clock and that by knowing this we have no excuse to not seek to redeem the time.

…By the way, you are, hands down, the most gifted and thoughtful writer I have had the honor of teaching in my 20 years as a professor. Your voice is beautiful. Let no one ever hinder you from composing in the key of life. You were born to write. Peace & Blessings, Professor Fountain

Kay wrote back: “…I know you mean every word and that means the world to me.”

I could say the same about Prof. Reid. It mattered not that I was Black and he was white. It matters not that Kay is white and female and that I am Black and male. This is one of the lessons my professor taught me. And it has never been clearer.

‘The Fragrance of Fresh Lilacs’

I NEVER GOT CLOSURE. That is the epiphany gained after much soul searching. I had received the sudden news of Prof. Reid’s death. Then days later, a Christmas card he had sent before he died arrived at my home by U.S. mail. That always felt weird, unsettling in a way—to read his words written to me on the card and having to reconcile that he was now dead, gone.

I attended Prof. Reid’s memorial in February 2005 (his services were private), where I spoke as one of his former students. But I never had the chance really to say, “goodbye,” or at least “until we meet again.” I knew he was sick, but I thought, perhaps fool-heartedly, that there was more time.

I have come to see this oversight about time as a human failing. And I have come to know that time and life are as fleeting as a summer’s breeze. That seasons can slip through our fingers.

Time. It is not on our side. Every day I am reminded that time passes without apology, sifting memories and melodies of the past, whispering upon the wind to those who will hear her that your time too will soon have come and gone: The time for making a difference in this world. The time for being a journalist. The time for being a professor. The time for writing letters that may someday speak from eternity and help refortify a former student with hope, faith and dreams of endless possibilities.

It was time, not coincidence, that carried Kay’s message to me, four days before the anniversary of Prof. Reid’s death at age 64. Time that led me, now at age 63, to return to my alma mater in search of solace, memories and marrow.

Since my mother’s death nine years ago, I have returned to her gravesite whenever my spirit is compelled. To pay respects and to be as near to her as I possibly can in mind, body and soul. Sometimes I need to hear her. To bathe in sweet recollections of someone who, even when the world said I was nothing and unlikely to achieve my dreams, believed that all things were possible. Someone who, despite circumstances and the odds that can cloud one’s vision, could always see me. Someone who believed in me.

Sometimes I need to go see my mother. Standing or kneeling near her headstone, I speak to her and allow memories of her loving, uplifting and restorative words to fill me. Like the words of my beloved mentor and professor. They rose like the fragrance of fresh lilacs from papers and letters inside the hushed archives of the University’s library, flooding my heart and soul.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com