It Matters That Tyre's Alleged Killers Were Black

"Tyre Nichols was fatally beaten by Black men about 20 miles from the Lorraine Motel, where 55 years ago, Dr. King was assassinated by a white man. ...My soul cries."

By John W. Fountain

THE FACT THAT THE COPS were Black makes it worse. A young Black man lynched by Black men in Blue, and propped up on the side of an unmarked Memphis police car like new “strange fruit.” I absorb the horror of it all and my soul cries.

That those Black men now charged with the murder of Tyre Nichols—sworn to serve and protect—could beat to death any man, let alone one who looked like them, like me, like their “sons,” brothers or nephews, pricks my soul with profound pain.

His kinky woolen hair, like theirs. His deep chocolate complexion, like theirs. And Tyre Nichols’ lifelong burden of being Black and male in America—imposed by a society in which we remain America’s most loved and also her most hated—is also their burden to carry unto death.

Tyre was the mirror reflection of themselves. And yet, with their hands—and feet—the police’s own video recordings show they viciously beat the life out of him without mercy in incomprehensible horror, the likes of which all of America and the world witnessed wreaked upon Rodney King, 25, in March 1991 by Los Angeles Police.

The nation also witnessed on video, 23 years later, the slaying of Eric Garner, 43, choked to death in July 2014, by New York police after approaching him for selling loose squares. Then came the unjust fatal shootings by police of Philando Castile, 32 (killed July 2016), Alton Sterling, 37 (killed July 2016) and countless other Black men whose stories have not yet—and may never—come to light, like many before them, buried by false reports, a blue wall of silence and the absence of videotape.

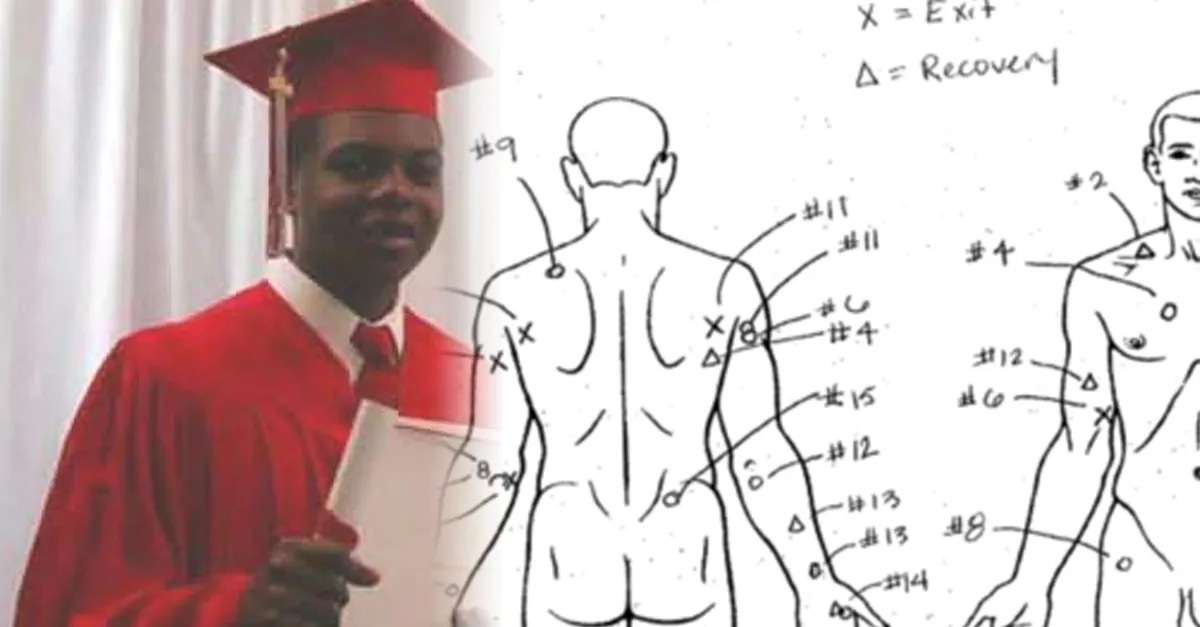

Like the inhumanity inflicted against Laquan McDonald in October 2014, by a since convicted, but now free, white Chicago cop who emptied his Smith and Wesson 9mm semi-automatic pistol into the 17-year-old’s body, shooting him 16 times as his body jerked and smoldered on an autumn night.

Like the terrorism against the body of Emmett Till (Aug. 28, 1955). Till’s murder is forever seared into the consciousness of Black America by that casket photograph of his grotesquely disfigured face and pumpkin-sized head, swollen from the torture of the two white men in Money, Mississippi, who later admitted to lynching the 14-year-old Chicago boy.

Then decades later: George Floyd, 46. May 25, 2020. For 9 minutes, 29 seconds, a white cop knelt on his neck until he was dead—a symbol of pure police savagery against the Black body. And yet, Tyre’s case still hits me differently.

Dead is dead. But isn’t the slaying of Abel by Cain even more objectionable, made more deplorable, the greater, if not unforgivable sin, by the fact that the murderer was not a stranger but his own brother?

The picture of Tyre, 29, lying in a hospital bed, swollen head and eyes from the brutal beating on Jan. 7, and who officials said succumbed to his injuries three days later, reminds me of Emmett Till. Different zip code, same address: America. Tyre’s slaying is indeed reminiscent of the countless bodies that dangled from poplar trees in the Deep South as symbols of racial hatred and brutality. It arouses within me the same sense of horror, pain and also questions over how any human being could inflict such inhumanity upon another.

Except knowing that the assailants of Tyre’s Black body were Black like him, like us, fills me also with a certain sense of wonder, hurt and rage reserved for betrayers. For it is the Judases that break our hearts, shock the system, cause us to lose hope or faith in all men. Et tu Brute?

I am not naïve. All skin folk ain’t kinfolk.

I have long been aware of the brutality of police officers—both white and Black. Have witnessed as a young Black man growing up on Chicago’s West Side the “jump-out boys” or plain-clothes detectives or tactical officers from special police units like Memphis’ SCORPION (and now disbanded) unit to which the accused and since terminated officers were assigned. I have witnessed the aggressive brutality of officers from special units and their harshness in the hood as they spring from their unmarked squad cars like hardened steroidal RoboCops, guns drawn, spewing profanity.

There exists the sentiment among many a Black man that to encounter a rogue Black cop can be worse than facing a white cop, especially a Black cop out to prove that he’s one of them, not one of us. And the knowledge of, and/or experience with their explosive hostility, profanity and willingness to rough you up, even for a traffic stop, can leave you just as nervous as seeing that it is a Black cop versus a white cop approaching in the sideview mirror. Not all. But too many.

In the street, we Black men are at cops’ mercy—Black or white. It matters not that you have no felonies, no warrants, no expired license or vehicle registrations, or have committed no traffic infractions. It matters not whether you are butcher, baker or candlestick maker, politician, preacher, lawyer, journalist or even a cop. We are all well-versed in the hazards of Driving While Black, of Living While Black. None are immune. Old or young.

And this is what makes the murder of Tyre Nichols by Black police officers even more egregious, more heinous, in my mind and soul. Why I could barely watch—as the video released by the authorities in Memphis showed Black hands drag Tyre’s young Black body from his car, beat him, and kick him repeatedly in the face and head, beat his thin Black body with a baton all the while he appears to show not a single ounce of resistance, until finally his limp body slumps into unconsciousness on the naked street. Why tears flooded my eyes I watched Black men beat the life out of Tyre, and in pain and torture his soul cried out for his mother:

“Ma, ma, ma!”

I cried.

They are the same tears I cry over the fratricide I have witnessed as a reporter for more than three decades now. Of the murder of young Black men by young Black men across America, from Memphis to Mississippi and Arkansas to St. Louis, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., New York and my hometown Chicago, where, according to police, 695 people (the vast majority Black males) were murdered last year and 2,832 people shot.

The murder of us by us has always struck me differently. Left me with a sense of puzzlement and dismay, even as I have always been cognizant of the particular occupational hazards of street life and drug dealing, and of the byproducts of systemic racism, poverty and socioeconomic oppression. Of the toxic soup created by human desperation, miseducation and the proliferation of guns—not just in America but in the hood in the hands of young Black men.

Of the fact that Black lives in America still don’t matter. Not even to us. And of the complexities of life on the other side of the tracks that are stubbornly resistant to social antidotes and catch phrases created in ivory towers by those who do not fully comprehend what it means to dwell in this American life in this Black skin.

The now former Memphis Black cops charged in Tyre Nichols’ death are without excuse. They cannot not know what it means to walk a mile in Tyre’s shoes as a Black male in America. To awaken each day and step beyond your front door, shouldering the millstone of walking out into a world where your Black skin makes you a suspect, predator, criminal and target for a police traffic stop that could cost you your life.

And no amount of police training can counter the poisonous elixir of inhumanity and unchecked power mixed with the license to dispense deadly force that can transform a peace officer with a predilection for violence and prejudice against Black men into street-judge, jury and executioner. Truth is: Policing isn’t broken, society is.

I have heard it said in recent days that the race of the officers in the Nichols case makes no difference. That this case highlights the need for police reform—regardless of the race of the offending officers—amid the historical and continued abuses of power by police. I cannot argue with the latter.

However, I respectfully disagree with the former, as I am reminded of my own epiphany in Ghana last year while touring the historic slave castles and other sites that shackled African slaves once tread on their journey into the Middle Passage. Standing in Assin Manso Slave River where Africans bound for American slavery were forced to bathe before the final leg to Cape Coast Castle—having marched as captors from various regions of Africa—one thing suddenly became crystal clear to me:

That the white man could not have survived the bush, heat and malaria, and that the slave trade could not have been exacted with such menacing magnitude and success without the cooperation and full participation of the Black man. It spoke to me of the Black man’s inhumanity against the Black man amid the opportunity to gain some measure of power by selling his African captives gained from wars with each other as slavery flourished in an already existent atmosphere of tribalism, intra-racism and self-hate.

And I ask myself, which is worse: The one who enslaved us or the one who sold us?

Dead is dead. But isn’t the slaying of Abel by Cain even more objectionable, made more deplorable, the greater, if not unforgivable sin, by the fact that the murderer was not a stranger but his own brother?

And if we Black men don’t first stop slaying and betraying one another unto murderous death, and doing the white man’s bidding, or beating, then who will?

Tyre Nichols was fatally beaten by Black men about 20 miles from the Lorraine Motel, where 55 years ago, Dr. King was assassinated by a white man.

And we are still light-years from freedom, and at least as far from finally loving ourselves as a race of people and ceasing from the Black man's inhumanity against the Black man. Still.

This much I know: I expect nothing from my known and identified enemy. But my brother? My brother, who, in reality, is become my enemy, masquerading in black face, and hiding behind police blue and a badge?

After all that we as a people have endured, Et tu, my brother?

My soul cries.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com