Ironing My White Shirts: A Ritual of Remembrance Prayer, Pressing, Perfection and Grandmother

Sometimes I need to clean my own shirts, with my own hands. Need to feel the fabric between my fingers. Hear Grandmother’s voice and recall those times when I had materially so much less than I do now

By John W. Fountain

I STAND WITH A hot iron, pressing the wrinkles of my white cotton shirt. The scent of starch mixed with a hint of Clorox and fabric softener fill my nostrils.

I breathe it in, relish the process of straightening with heat and precision. There is something about wearing a shirt cleaned and pressed by my own hands, even if this is a relic from the past.

Truth is: I can do as good a job as any commercial cleaners, though the lack of time at times over the years has necessitated having my shirts laundered. But with more time on hand, I indulge in the self-serving art of ironing. For it transports me to another time and season, like an autumnal wind that carries scents of bygone days, of faces and places that live now mostly in the recesses of my heart and mind.

This practice of ironing resurrects them. Soothes me. Restores a part of my soul, in one sense, the way a brisk walk through an emerald tranquil forest preserve—surrounded by and yet removed from the world—provides respite from the static. My ironing ritual reconnects me to Grandmother.

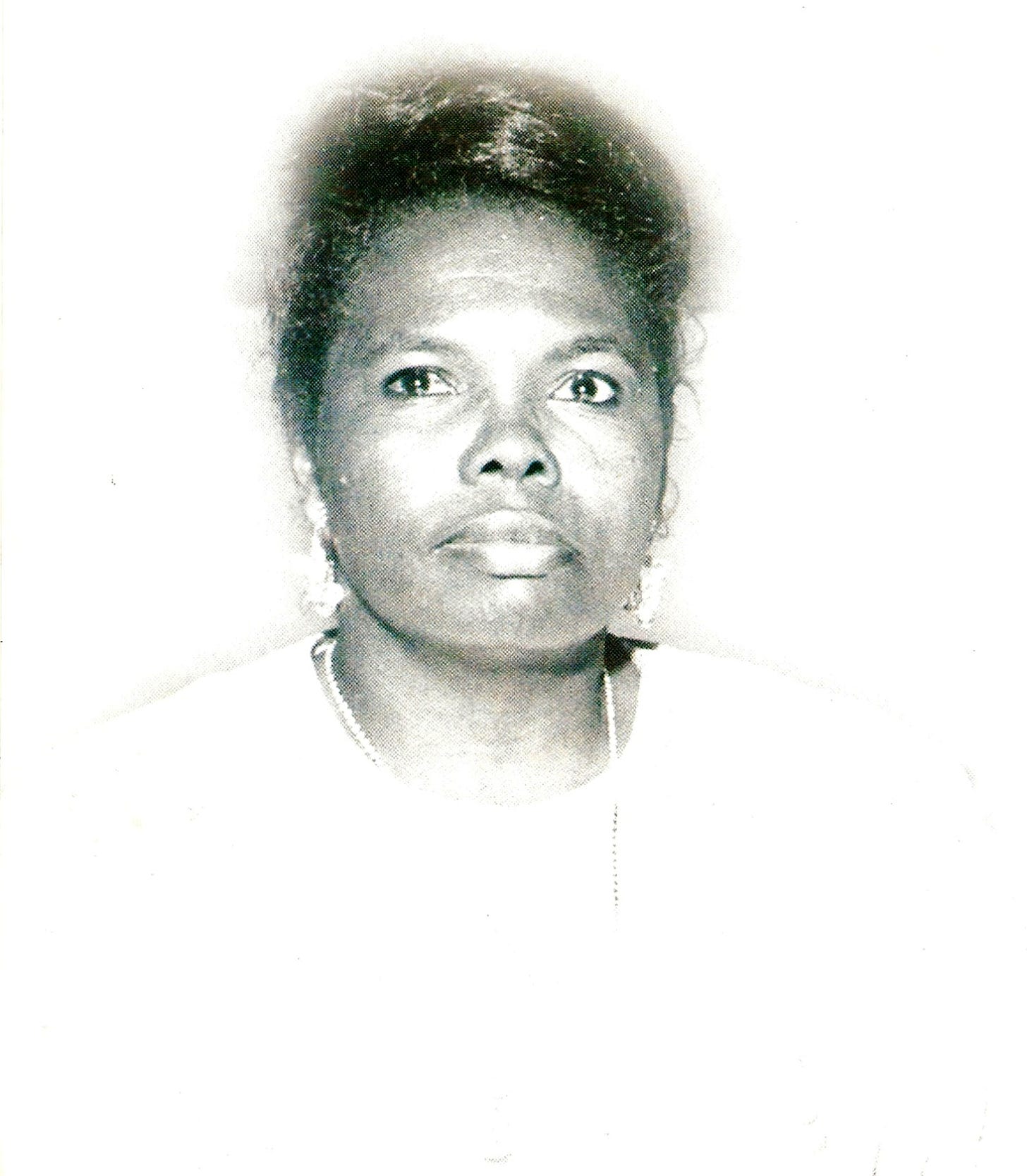

‘Florence Fashions’

GRANDMOTHER—FLORENCE GENEVA HAGLER—was a seamstress. She worked for years at the Kuppenheimer clothing plant on West 18th Street, around the corner from where we lived on Chicago’s West Side in K-Town. And in as much as she was an expert on Pentecostal “holiness,” faith and prayer, she basically held a Ph.D. in stitching, quilting and all things related to clothing. It had been earned over years of making dresses, suits, skirts and blouses for her granddaughters and even a few suits for me.

Among my favorites was a Lima bean green gabardine three-piece suit she made for me in high school and that drew envy of some of my friends. I told them my suit had been tailor-made: “Florence Fashions.”

I watched Grandmother stitch with the same passion and purpose with which she kneaded dough from scratch for her divine peach cobbler, or quilt, and which began in the wee hours of morning before the sun rose and which concluded after days and weeks with the creation of another splendid blanket woven into a multicolored tapestry that was itself a piece of fine art.

I watched Grandmother quilting and stitching. But I studied the art of her ironing.

My process begins with plugging in my steam iron, then laying a clean white towel atop my ironing board, mostly to avoid collecting any spots that may be undetectable to the naked eye. Sometimes I retrieve the shirt from a chilly plastic bag I had refrigerated. This was Grandmother’s way.

At other times, I pull one or two or three from hangers in the laundry room for my usually morning pressing sessions. I push a button and steam hisses in this meticulous ritual I learned many years ago under Grandmother’s tutelage. I can still see her. Hear her.

Remember the clunky white washing machine with the wooden roller wringer that if you weren’t careful could consume your fingers. The wooden and hard plastic washboard that stood in Grandmother’s metal basement sink that she used to rub out stains with determination and bare knuckles.

“Place a little detergent on your collar and cuffs before washing your shirt,” Grandmother instructed, her words rinsed with wisdom, craft and love. “And make sure you scrub your neck and wrists before you put your shirt on, JohnWesley,” she’d say, fusing my first and middle names.

“Okay, Grandmother.”

I hated when she called me JohnWesley around my friends. But I loved it otherwise. It made me feel special. Grandmother was the only one who called me that. Our bond.

Grandmother’s way of transforming soiled white shirts—once they had been thoroughly cleaned—into crisp bright swans was to starch them.

“Only starch the collar and cuffs, JohnWesley,” Grandmother coached.

Boxed starch, she explained. Not that spray stuff.

Then sprinkle the shirt with a little water, place it in any clean plastic bag. Throw it in the refrigerator for a few minutes. The result was a chilled shirt whose wrinkles were more submissive under the glide of a steamy hot iron.

As a man, I have sometimes cheated, choosing the easier less involved route of spray-starching my shirts, though without the full stiffening result of Grandmother’s way.

Prayer, Pressing and Perfection

AS A BOY, I watched Grandmother perform her pressing ritual many times on Grandpa’s shirts. And I watched her quilting blankets in the early morning inside an upstairs bedroom turned sewing room that was filled with a library of needles, thread and various colorful cloths, and also assorted patterns for dresses and suits. The rumble of the sewing machine sometimes awakened me like a cock’s crow on a sleepy Mississippi farm.

Thimbles, needles and thread were among her tools. In her makeshift tailor shop Grandmother and I engaged in endless conversations about life, in between recitations of Bible verses and her sudden innate utterances of praise.

“Jeeeesus, you been mighty good!” she’d shout in an instant. “Won-der-ful sav-ior… My, my my…”

Praises to God were never far from Grandmother’s lips. A labor of love never far from her strong but gentle hands. And the lessons she taught me, even after all these years, never far from my heart.

I am reminded that once upon a time, I had only one white dress shirt. Cleaning and starching it, sometimes nightly for church—especially during our month-long church revivals in January—was a matter of necessity. Back then, I had more time than money. Then one day I had less time. So I started taking my shirts to commercial cleaners.

They break my buttons. Alter the fabric of my shirt by starching the whole body. Rip it. And even when they get it quite right, it offers only a measure of satisfaction.

Sometimes I need to clean my own shirts, with my own hands. Need to feel the fabric between my fingers. Need to iron. Hear Grandmother’s voice and recall those times when I had so much less materially than I do now. And yet, they were times when I had so much more than I could ever have realized.

As I iron, the wrinkles in my white shirt melt. The scent fills my nostrils. And memories of another life and time and Grandmother flood my soul.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com