Dear Sister, Why Didn’t You Talk To Me Before You Ran And Told ‘The Man’ On Me?

'Inasmuch as I encountered offenses from people inside newsrooms who did not look like me, the ones that stung most were from those who looked like me and who I assumed were my brothers and sisters'

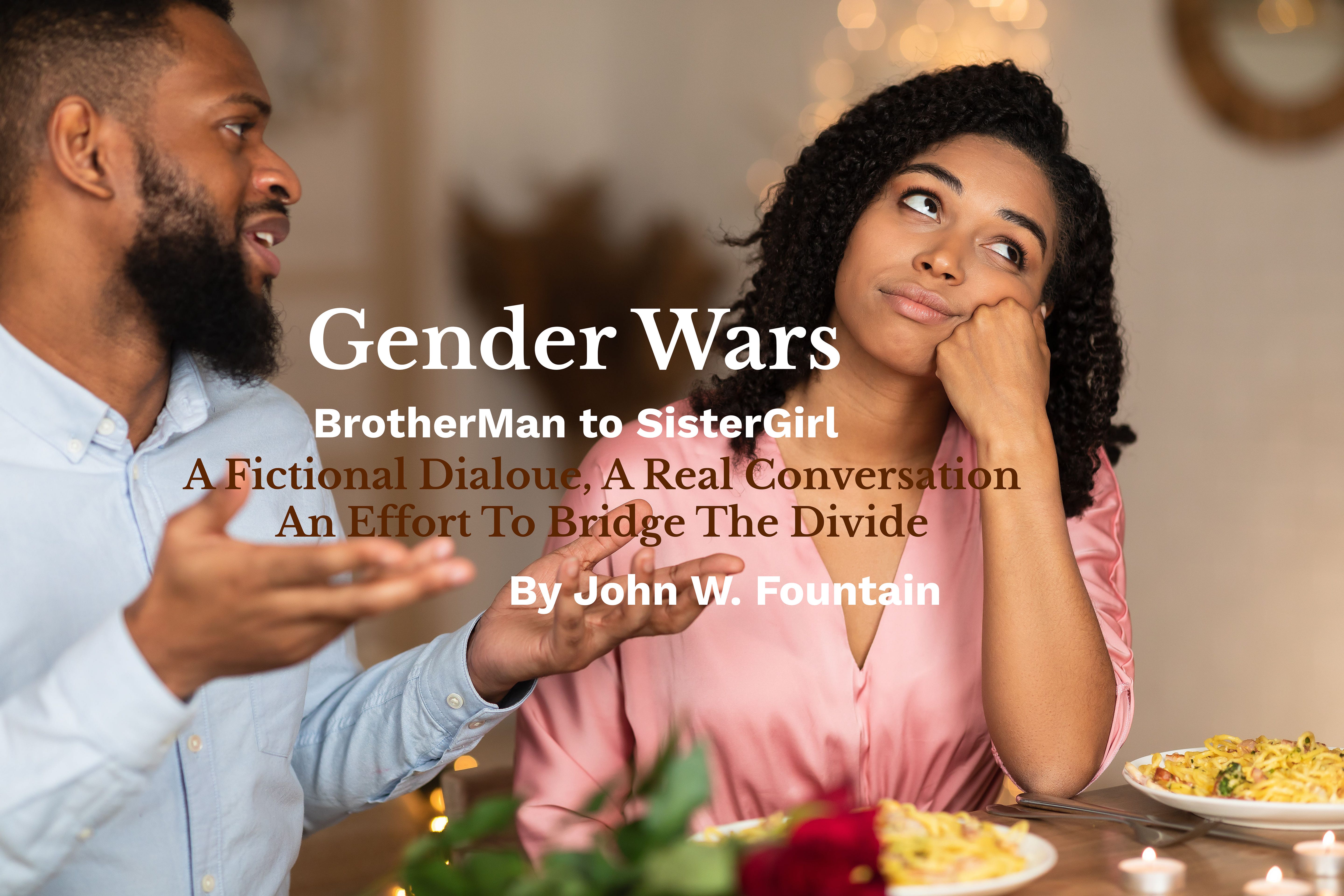

This column is a real letter written by the author once to his editor in response to a fellow Black female journalist who took offense to a column John Fountain had written and published in the Chicago Sun-Times about a satirical conversation between a Black man and a Black woman (BrotherMan to SisterGirl). The offended journalist complained about Fountain’s column to the editor, who is white, without first voicing her concern to Fountain and giving him an opportunity to respond. The letter provides a window into John Fountain’s career journey inside American newsrooms, to the tumult he faced and sometimes the justification he felt compelled to make, particularly as a columnist seeking to tell his truth, from his perspective, in his own unaltered words—sometimes amid opposition from journalists of his own race. The original column in question appears at the end of this writing. Fountain is at work on a forthcoming book, “50 Cent A Word: Diary of A Freed Black Journalist.”

By John W. Fountain

“HI TOM, I AM writing to you, primarily prompted by a voicemail left at my office by (my colleague) and a subsequent conversation with her last evening. She relayed that she had “conveyed” to you her concerns over Thursday’s column, saying in part, “I found it deeply, deeply offensive” and explaining that she became concerned after receiving calls from women readers.

I don’t know that I need to rebut my “colleague,” but I do think I need to say a few things in the name of clarity.

First, as a Black man, I am well aware of our sensitivity (sometimes ultra sensitivity) as a people, regarding certain issues, in part, because we have been too often typecast, stereotyped, misrepresented and caricatured by the media.

As a writer, particularly one who writes social commentary, one always runs the risk of offending. That is never my aim. But sometimes, offense is unavoidable. What I hoped this piece would do is what I hope of most of my writing as a columnist: That it might provoke thought, perhaps bring insight, perspective, challenge, and also allow readers to draw their own inferences or conclusions. It’s never my job to tell people what to think or how to think, only what I think, which is what you’ve asked me to do since the beginning.

Complainant Colleague: “I’m not sure why you took this tact or felt you had to provide this stereotypical view of a Black woman.”

It is a real view. A real woman. Black. Educated. Single mother who raised four children. An entrepreneur, writer, Christian, church-going Black woman. An overcomer. That’s her voice. Not mine. Authentically shaped in experiences that while they may not be the experience of all Black women are no less legitimate, and indeed undeniably reflect the travails and perspective of many women like her. (I’d be happy to pass along her phone number.)

The brother’s voice is mine. And not just mine. But in a sense, it is a reflection of the countless conversations I have either engaged in or been privy to for much of my adult life (I’m 53). It is a collective of those Black male voices—authentic, and while not completely no-holds barred, raw in the sense of what is said in our private cultural conversations on this matter, right down to the sister’s and the brother’s “hood rat” comments.

What I hoped to capture in that dialogue as well was real language that transpires in secret every day, to give a degree of authenticity to this fictional but realistic conversation, capturing the nuance and full range of emotion of it all. If one reads closely, what I hope they will see are two people who want the same thing, but whose hurts, fear and mistrust, as well as their baggage, become hurdles to a functional relationship. I can write it that way—straight no satire, no chaser. But as a writer, I trusted that the reader would “get it,” even if I chose a different form or method to convey those thoughts. Maybe I presumed too much.

Thursday’s piece was a social slice, a snippet. Not a treatise. Not meant to be a reflection of all Black women or all Black men any more than my writing about the church and pastors who prey on the poor is meant to indict all churches and all pastors. Anymore than writing about Black men who sag is a reflection of all Black men or even my sons. I think reasonable people get that.

Complainant Colleague: “I found it deeply deeply offensive... That’s just so derogatory of Black women.”

I find deeply offensive that some mothers trade their daughters in sex for drugs. I find offensive the images of Black women portrayed by Black women on shows like “Basketball Wives,” “Real Housewives of Atlanta,” and “Love and Hip Hop,” in full inglorious vulgarity and weave-snatching fervor. I find offensive that I hear educated Black women with Ph.D.’s and MBA’s using the B-word as a term of endearment, something (my colleague) acknowledged exists.

I find deeply offensive young college students starting a “light-skinned club” and referring to their sisters as “jigaboos.” Offensive the names we as a people call each other as a point of denigrating, dehumanizing and damning. And yet, if I, an educated Black man, peering through my lens at the social landscape, choose to write about any of this in a way that captures its authentic ugliness in the hope of possibly spurring change, I run the risk of being offensive. It is offensive. And sadly, it is the truth.

Complainant Colleague: “I didn’t understand how the editor let that get into the paper.”

I, myself, find this deeply offensive. As a journalist for about 30 years, I have proven myself capable of doing journalism that is, I think, up to standards. And the content of this particular column, coupled with its context and the context of the body of my work as well as my character, which has consistently promoted the posterity and wellness of Black people, ought to be enough to cause at least my “colleagues” to not rush to judgment.

That much is clear in my columns—from tributes to my grandmother and mother Gwen Clincy, to defending Gabby Douglas against the barrage of criticism (mostly by Black women) over her hair; to remembering the glamour of Harriet Tubman, writing in praise of single Black moms who hold it down, of my own daughter, in praise of Black women, publicly and privately, more times than I can count. And for none of these, or for any awards I have received in the last four years, have I received to date even one note from my colleague or any other Black woman on the Sun-Times staff. Not one. But that’s not why I write.

If (my colleague) is suggesting more sensitivity, I’m not sure I could be any more sensitive. I carry the hearts of every Black woman who has nursed, nourished, lifted me and prayed for me. If it is censorship that she’s suggesting or that my maleness or perspective somehow preclude me from writing about Black male/female relationships or even about Black women, as I see it, that is a different matter.

I call it like I see it with each column. And I bring to bear all of my journalistic ability and experience with my heart and passion for telling a story. That’s always how I got my stories into the paper. Plain and simple.

Complainant Colleague: “Women were not happy. They were offended and they were hurt…”

I have no doubt when I write that not everyone will be pleased. It is the curse of being a columnist. (My colleague) said that four women called her to say they were offended by the column. I explained to her that the Sun-Times is the 9th largest newspaper in the country and that four doesn’t constitute “many,” as she initially purported to me. We both agreed that “some” was a fairer assessment. And I’m glad because there were also some who did “get it.”

From a Black woman reader: “Pop your collar Mr. Fountain! You and I know the "Talking BrotherMan to SisterGirl" was not just a 'fictional dialogue' between you and your colleague, it is an unfortunate departure that happens everyday between an eligible man and a disconcerting woman...Black. Thank you for addressing this issue!

From another Black woman reader, in part: “…The article is a relatable piece...especially for sistahs that have good guy friends that talk S#$% to each other all the time. Also, it was and is my truth (depending on my day...)

“I'm an official Super Souler (OWN Network)... So I say all of that to give you context to my reasoning for not being offended... Why should I? I'm not insecure... I appreciate “real talk" especially when I hear my own voice! I (SisterGirl) am Soloman Northup's Anne Hampton...

I'm truly trying to do the work so that I can attract my heart's desire; therefore, this SisterGirl...is now...SisterWoman...”

‘Sounds A Lot Like SisterGirl’

Tom, I apologize for being long-winded. Almost done. One more voice I’d like for you to hear—a familiar one:

“Say it ain’t so. How could the person who uttered the infamous indictment of President George Bush during Hurricane Katrina — telling the whole world Bush didn’t care about Black people — hook up with a white woman who Black women love to diss?”

…With the public unveiling of Kanye’s new love, some Black women are asking, what the heck?

Like too many other rich and famous Black men, Kanye runs right past Black women and straight into the arms of the white woman, or the closest thing to one.”

Sounds a lot like SisterGirl to me. But, of course, that’s my esteemed colleague Mary Mitchell. As a Black man, I am not offended. As a columnist, I may not agree with what she or another columnist says or even how they say it. But I respect that they do and that they attach their name to it for the good, the bad and the ugly.

Finally, as I said to (my colleague) last evening, she was right and obliged to inform you of her feelings or of any reader reactions. I just wish that as a colleague, in the name of collegiality, she would have expressed those concerns first to me and at least given me the opportunity to address those concerns as I have here. Isn’t that what colleagues, friends, fellow writers do? Maybe not.

Thanks, Tom, I’ve taken the liberty of copying (the complaining colleague) and another Black woman journalist) on this note since they both reached out to me yesterday. Sincerely, JOHN”

‘At A Cultural Disadvantage’

DAYS LATER, MY EDITOR wrote back: “Hey, I never got back to you about the column last week. I thought my colleagues had interesting points, but I wasn't inclined to take sides or to side with them against you. I also feel culturally at a disadvantage in this one—what do I know.

My general view is that you write stuff that I don't see elsewhere (taking, for example, the importance of the church to African Americans deeply seriously) and that's good.

But that kind of exchange you had with (the two Black female journalists), as we both know from years in the business, actually is helpful in the long run, uncomfortable as it can be. Hope you're doing well with all this snow.”

‘All Skin Folk Ain’t Kinfolk’

THE TWO BLACK WOMEN journalists I had copied on the letter to my editor never wrote me back. It doesn’t matter. But 10 years later, and with the Sun-Times and daily newspaper journalism in my rearview mirror, I still can’t shake the incident from my memory. Nor the hurt or my difficulty in understanding why this wound still runs so damn deep.

The more I have unpacked it, the more I have reasoned that as the only local Black male columnist between Chicago’s two big daily newspapers, I already felt like I was alone on a deserted island despite having both external and internal supporters. But writing about race, the Black church, Black life, and Black women’s hair, among other subjects, is prone to draw the ire of critics and mean-spirited, sometimes threatening emails and letters.

I was keenly aware of the existence of those who wished John Fountain’s column would just disappear and that I would just shut up already. I strongly sensed that this feeling also existed among some even within the Sun-Times. In fact, I hesitated to accept the initial invitation from Tom McNamee, editorial page editor, in late 2009 to write a weekly column because I did not believe this city or the Sun-Times, for that matter, really wanted to hear what a brother from the other side of the tracks had to say about Chicago and the world beyond. That I might be, uh, too Black.

It soon became clear to me that a lesson I had learned long ago was also applicable in this case: That all white folk are not your enemy and all Black folk are not your friend.

By my so-called sisters’ actions over my column, I felt blindsided and backstabbed, betrayed even. My thinking was simple: If a fellow Black journalist—man or woman—had taken issue with something I wrote, why wouldn’t they seek to speak with me before taking their grievance to the editor, black or white? That’s certainly what I would have done.

I said as much to the one sister I spoke with by telephone before feeling compelled to write an internal follow-up letter to the editor in my defense. I also asked her why she hadn’t simply called me to begin with.

“…You know me,” I explained, searching for understanding. “We’ve known each other for years…”

She explained smugly that it was her right to speak with the editor. I told her I certainly agreed, but added that it still didn’t explain why she hadn’t talked to me about her issue with my column. Turns out that after she took her grievance to the editor, he asked her simply, “Have you talked to John?”

She explained that she didn’t write to me because, “I didn’t want to end up in your column.”

Well, here we are, 10 years later.

In her defense for not calling, she said that she didn’t have my phone number. If she didn’t, I explained, my email and office phone number were Googleable, and my schedule and vitals as a professor posted on my university’s website. And even if that wasn’t the case, finding a phone number is small potatoes for a big-city reporter. Her explanation was hogwash.

I understood then that her point was never to gain any perspective or insight about my rationale for the column. It was to hit back, to try and get me in trouble with the boss, so to speak. But why?

It soon became clear I had struck a nerve. I later reasoned—and some Black women I trust explained to me—that my column had apparently hit home, likely stirring some preexisting ire over a broken or bad relationship with a Black man or men, thereby scraping the scab of unhealed wounds. And that whether it was my intention or not, she had perceived my column as a vitriolic attack on the institution of Black womanhood and possibly the entire African female diaspora.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Context is everything. And the context of my writing, my love and my commitment to the praise, promotion, protection and posterity of Black people has over decades become synonymous with my byline.

As the only Black male local columnist for years between Chicago’s two big daily newspapers, I was always prepared for criticism, flack and static from the outside and even from the inside. But from my own?

Inasmuch as I encountered offenses from people inside the newsroom who did not look like me, the ones that stung most were from people who looked like me, people who as African Americans I assumed, rightly or wrongly, were my sisters—and brothers. But here too in American newsrooms, where fierce competition, jealousy and the desire sometimes to curry favor from white editors and the powers that be could be divisive forces even between kinsmen, stood this glaring lesson: That all skin folk ain’t kinfolk.

It is a lesson I hope many young Black journalists learn long before I did as they navigate the sometimes-dicey uncertain waters of a career in journalism, where obstacles and enemies sometimes blend like chameleons, sometimes pose as kinfolk and friends.

Many years after my journalism career began, I was conversing with a Black woman—a close longtime platonic friend, journalist and media guru. She remarked to me that from her observations many of the slights, hardships, mistreatment, insensitivity, microaggressions and difficulties I had faced over my career as a Black male journalist had come at the hands of Black women in the business. Truth is, I had never thought about it that way. But the more I thought about it, I could not argue against it.

I always saw Black women in the newsroom as my sisters, and Black men as my brothers. My painful reality, however, is that they didn’t always treat me the same.

That one fact resounds as loudly as the uncomfortable, yet still glaring truths of that conversation between BrotherMan and SisterGirl.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com

The Column, originally published in January 2014:

Gender Wars: This is a fictional dialogue that grew out of a real conversation between the author and friend Lisa Maria Carroll.

By John W. Fountain

SisterGirl: You’re supposed to be a man and lead. Why won't you stand up and occupy your rightful place...

BrotherMan: You’re right, baby, you right... OK, let's get ready to go…

SisterGirl: You don't tell me what to do, buster, @#!@#! You're not the boss of me!

BrotherMan: Huh?

SisterGirl: OK, first, where we going? See, ‘cause I promised myself and God that after the last man led me astray, I wasn't gon’ follow nary another. But I do want a man who is committed to God—a strong man, a leader, not a follower.

BrotherMan: Sorry, sister, I'd rather be by myself. You’re too HBC: Hurt, Bitter and Complicated.

SisterGirl: I'm not bitter! You must have me confused with one of them hood-rat chicks you’re used to messing with. And that's what I'm saying right there: Y’all would rather mess with women y'all can control than come correct to a strong, independent, Black woman.

BrotherMan: Really? Really? No, what I want is a woman who doesn't think that she's the King and I’m the Queen. And oh, I got your hood rat. At least all they want is a little cheddar!

SisterGirl: A REAL man already knows he’s the King, and doesn't have to be validated by any woman.

BrotherMan: Go ahead then. Be strong, independent, Black and a woman. Be all you can be. And be by yourself! I mean, I can’t get no respect, then you turn around and do whatever your pastor says.

SisterGirl: Don’t you dare bring my beloved pastor into this. He got the type of marriage I'm praying God will bless me with someday. He just bought the First Lady that new champagne Caddy CTS coupe, and she be fly e-ve-ry Sunday. Wha-a-a-t?

BrotherMan: See, you trippin’ now. Maybe he bought her that Caddy to make up for being some other sister's baby daddy…ha! Look, you’re confused. You don’t want a man. You want a boy—someone you can boss around; a toy—someone who will only bring you pleasure; a showpiece—someone for holidays and special occasions—the final piece of your picture-perfect puzzle. Not a real man, one who thinks and disagrees with your butt sometimes, but who still loves you completely. Don’t go chasing waterfalls…

SisterGirl: Just so you know, Mis-ter, I gots my boy-toy that I keeps in my back pocket until a REAL man comes along. I can't take him to church or around my family, because he's not as polished as I would like him to be. But he handles his-s-s. Know what I'm saying?

BrotherMan: And how’s that workin’ for ya? Bwaaaaahahaha!

Sister: Honestly? I don't hold out much hope for him because he'll never be on my level. But with so many Black men in prison, on the down-low or openly gay, we Black women have to settle for what's left.

BrotherMan: You know what? I can do good all by myself. Shee-ee-eesh…

SisterGirl: Naw, I think you'll do like all the other brothers and go get you a white girl, because we’ll NEVER be good enough for you.

BrotherMan: You took the words right outta my mouth! …So many hurt and bitter sisters leave us no choice. But I'm holding out hope for my beautiful Black queen... just not you, honey child. Deuces, I’m out.

SisterGirl: Before you cross that color line, remember that there wouldn't be so many hurt sisters, if it weren't for Black men.

BrotherMan: Yeah, starting with your no-good daddy! Look, no man can heal all your hurts and issues that were there long before we even showed up. Yet you blame all of us, in some cases, for what you allowed a man to do to you. I’m gon’ pray for you, sister, for real. Peace.

SisterGirl: Whatever, dude. Bye!

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com