An Easter Sunday Message For A Soul-Broken City: 'Peace, Sweet Peace'

'I am filled with more questions than answers before this bronze mournful Christ and the invisible river of tears of mothers who have buried daughters and sons, and of more rivers of tears to come.'

By John W. Fountain

CHICAGO, March 31—Behind a wrought iron fence on the South Side as the sun begins to rise above this soul-broken city early Easter Sunday morning, the message of two silent bronze human figures is deafening. I can hear it though, speaking with urgency and alarm as I stand here alone just off the corner of 79th Street and Racine Avenue.

A red, black and green “Black Lives Matter” flag flutters in the cold wind against a mostly cloudy sky with intermittent patches of blue. And the message of the two life-like figures permeates the cacophony of chirping morning birds, and an occasional passing automobile or pedestrian spotted here or there.

The sculpture’s message shines, even amid the ugly truth—and the beauty—of this artist’s portrait of murder in Chicago that has claimed many thousands of lives since my time in the late 80s and early 90s as a crime reporter in this city. It is a glaring and fitting Easter Sunday message. And perhaps a prophetic and requisite sign of the times.

Its message glistens like the mostly Black and brown faces of young men and women, boys and girls, sons and daughters—souls too soon gone home—now encased in a memorial wall. The portraits, many of which I recognize from my own reporting—form the backdrop of the bronze life-like sculpture that in some strange way beckoned me here to the sidewalk outside the Faith Community of St. Sabina.

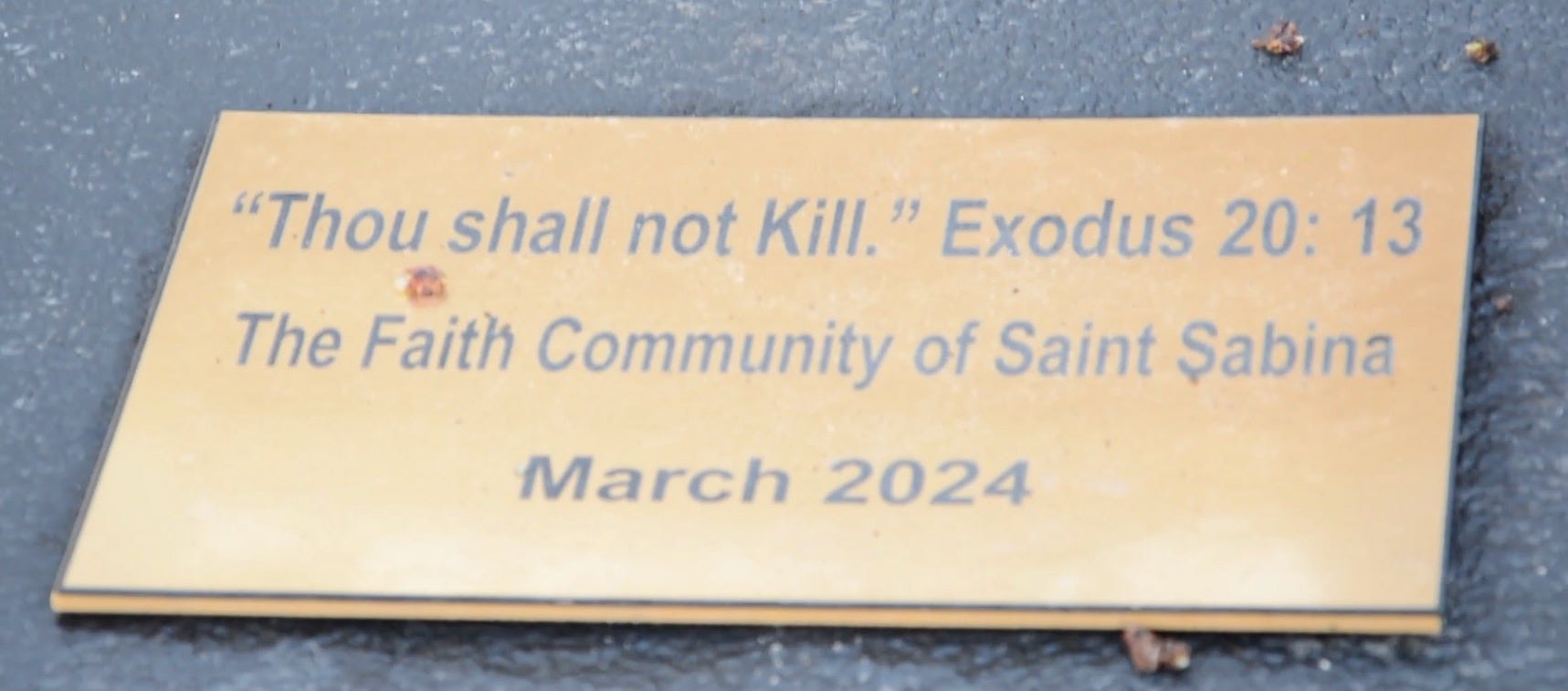

Titled, “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” the sculpture was unveiled early last week (Monday, March 25) on the grounds of St. Sabina during a livestreamed ceremony. The christening coincided with Holy Week.

“I cannot believe how many have come by in the afternoons and evenings to stop and look and pray,” Father Michael L. Pfleger, St. Sabina’s senior pastor, told me. “When we unveiled it, most of the mothers there who have lost children to gun violence began to cry.

“One screamed out because they each saw their child in that person lying on the ground, as did I. It’s how I found my son just two blocks from here,” said Pfleger, referring to his foster son Jarvis Franklin, 18, who was fatally wounded in a gang crossfire in May 1998. “If one person is convicted to say’, I can't do this anymore,’ it is worth it...”

The sculpture compelled me, for reasons I do not fully comprehend, to dwell here for a little while in its presence early on Easter morning. To absorb it and to try and decipher for myself its meaning as the sun rises on Resurrection Sunday. A day that my Aunt Mary and other church folk assured when I was a child that you could see the sun dance in declaration and celebration of the risen savior. Except I have never witnessed it.

Indeed as an adult, I later came to believe that people sometimes see what they want to see. I came here this morning to see what is—having glimpsed days earlier photos of the stirring sculpture’s unveiling on social media.

Perhaps I have also come to pay respects, to mourn.

Filled With More Questions Than Answers

I have also come in a few moments of solitude before this poignant symbol to reflect on why the scourge called murder continues to ravage and traumatize Black families and neighborhoods, leaving a trail of blood, tears and broken lives and mothers in perpetual mourning.

Perhaps to wrestle with why so many Black churches get all worked up about Easter, overflowing with pomp and circumstance and religious piety, filled with people in their Sunday best and brimming with Easter spirit. But on the other 364 days of the year, the church lacks the zeal and resolve to confront issues like murder that so afflicts us, choosing instead a less activist or social justice transformative approach.

I wonder silently: Isn’t that the real meaning and message of Easter? The matchless power of Christ’s resurrection?

Perhaps I have been led this morning to this city street—also marked by a brown street sign that reads, “St. Sabina Way”—by my own wonderment and deep-seated questions about the church and what I have often deemed to be the church’s disconnection.

I ask: What is the message to Black communities dotted with churches and yet blighted by crime, poverty and hopelessness? How can the church so relish and bask in the glow of a divine message of power and resurrection when it dwells in communities overrun by powerlessness, pure evil and death, despite the church’s presence?

How can so much so-called light not penetrate so much darkness? How does so much hopelessness abide—unencumbered by so many so-called houses of hope that dot the urban landscape?

Isn’t every day, for the Christian, Resurrection Sunday?

Has the church not been called to live out the Easter message of empowerment and hope every single day beyond its walls? Why is the greatest, most resilient, consistent and committed pastor of a Black church in Chicago that I have ever known a white Catholic priest? Why does Father Pfleger love “us” so much? Why won’t we hold all our churches and pastors more accountable?

I am filled with more questions than answers as I stand before the bronze mournful Christ figure and the invisible river of tears of mothers who have had to bury their daughters and sons, and more rivers of tears still to come.

‘It Breaks The Heart Of God’

I snap photographs and study the bronze sculpture of a kneeling Jesus Christ between sprays of pink, yellow and red flowers. His nail-scarred hands cover his weeping face. The object of his tears is the body of a young man wearing a hoody. Three bullet holes pierce his back.

The folds in their garments seem to shimmer in the light, enhance their human likeness. Their contrasting physical positions—one kneeling, the other face down and sprawled—illustrate life and death. Nearby a golden plate is emblazoned with the words: “Thou shall not Kill” Exodus 20:13

Collectively, the sculpture summons a swell of emotions within me: A deep sense of loss and anguish over the senselessness of murder. An almost inconsolable and incomprehensible agony over the incalculable toll that the murder of us mostly by us has wrought upon us.

And yet, I do not cry. I am not callous. Just short on tears after all I have seen and written over the years.

The sculpture is the work of Timothy P. Schmalz—a Canadian figurative artist who donated the piece and whose works have been installed worldwide, including at historical churches in Rome and at the Vatican. It will undoubtedly move many here to tears. In fact, it already has.

But the purpose behind it is much greater. To not just move observers to tears, but to action.

Pfleger explained, “No. 1: We “want to understand that the faces on the memorial behind this sculpture were not children who just died, they were murdered. We are killing our future and we are all less because the gifts they were birthed to share are now buried.

“No. 2: The scripture is there to remind us these are not just random shootings. This is Murder.

“No. 3: When Killing takes place, Jesus weeps. It breaks the Heart of God.

“No. 4: We did it during Holy week because it is the week that we remember another murder on Calvary.

“No. 5: Violence seems to be normalized in this city and country... It’s as if we have to accept it. We wanted to put it in the face of us all again. The sculpture is painful to see, but sometimes it is the ugliness and pain of it in our face that is needed to wake us up.”

I am wide awake as I stand here on Easter, studying the soul-stirring bronze sculpture. I stare east toward the rising sun before 7 a.m., detecting no distinguishable flicker than on any other day.

But the streets of Auburn-Gresham, for now, are filled with a palpable peace, sweet peace. It is a fitting Easter message for the soul of a broken city.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com