An Aged Door of A Segregated Outhouse: A Window To Our Past, A Call To Never Forget

'What I remember most about outhouses, inasmuch as they were once upon a time a necessary part of life, is that they were a symbol of the depth of American apartheid and segregation’s dirty shame...'

By John W. Fountain

AS A LITTLE BOY headed from Chicago down south to Mississippi in the 60s, Mama gave me “the talk,” born out of the history that had occurred in a town called Money involving another Black boy from Chicago five years before I was born.

My family—the Haglers—knew the family of Emmett Till, united by faith and the “sanctified church,” or the Church of God In Christ, which bonded so many Black families from the South and beyond.

“When you get there, don’t talk back to white people,” Mama had said. “If you go to town to buy candy, just get what you need and leave.

“And don’t say nothing to white women!”

Mama told me what had happened to Emmett Till at 14, speaking in solemn tones and with attention to detail like a meticulous historian. I was a dark-coffee-complected prepubescent boy with a penchant for the outdoors and occasionally accused by my cousins of “playing too much.”

Mama explained, as I listened with pain piercing my belly, that white men had killed the Black boy after he was accused of whistling at a white woman. How they had come to his family’s house and dragged him away into the night then beat him mercilessly, gouged out his eye and shot him in the head, then tied a heavy cotton gin fan with barbed wire to his body before throwing him into the Tallahatchie River.

Mama explained that Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till, after seeing her son’s grotesque and swollen face and head when his body arrived by train back in Chicago that August summer day, had decided she would have an open casket so that the world could see what they did to her boy.

Photographs I would later see of Emmett in Jet Magazine are still emblazoned on the pages of my psyche and soul—that particular lesson in history since passed down to my own children. I would not forget.

‘The Scent of Southern Heat’

AS THE CAR’S WHEELS rolled over the highway toward Isola, Mississippi—the home of my stepdad (Eddie Clincy)—I remember feeling half-excited and also half-afraid about the journey south of the Mason-Dixon. Excited about meeting his brothers for the first time, some of them close to my age or the same. Excited about getting to experience life on a farm—chickens, hogs, snakes and green fields, fishing.

Anxious too about the unknown and the prevailing sense of fear instilled in me by what my mother had told me about the way white folk treated Black folk in the South; how they had murdered Emmett Till; how they hated Dr. King; the bitter realities of southern segregation. Those realities dictated even how we traveled: leaving Chicago by car in the wee hours of the morning so as to arrive in Mississippi in plenty of daylight.

Instructing us kids not to lollygag if we did happen to stop at a gas station restroom along the way, to do our business, but to say absolutely nothing to white folk and hurriedly get our black butts back to the car. Sometimes we pulled off to the side of the road to do No. 1 or No. 2 rather than risk a bad encounter at white-owned gas stations. We also packed a basket with fried chicken, sandwiches, potato salad, chips, fruit and other snacks to avoid the risk of stopping, which could be dangerous, if not deadly.

Going down South, as we northerners called it back then, always felt to me like traveling in a vehicular time machine, rolling past Illinois prairie and cornstalk-filled emerald terrain that eventually turned to cotton fields mixed with the scent of southern heat, peril and uncertainty.

I remember when we first pulled up to the Clincy family’s humble abode on the side of the road—a shotgun house of wood and tin, similar to the kind I would later see in rural Ghana. It was anchored on either side by green grass and it backed to lush fields that seemed to stretch on for days into sprawling trees far beyond the hog pen.

For weeks, I frolicked on golden rays of southern sunshine, going fishing with my uncle Jimmy T who was the same age as me. We strode down blazing country roads in our bare feet, occasionally spitting brown tobacco juice with Ollie, a slightly older brother. Sometimes we went to town to buy candy and bubblegum, killing time, Jimmie T and me, dipping our fishing poles into murky ponds—catching small perch-like fish and crawdads.

We drank water that we summoned from a ground-well with a squeaky one-arm pump in front of the house. We awoke each morning to the sound of cocks’ crowing on their Mississippi Delta farm and to the aroma of blended scents of homemade southern cuisine that made my mouth water. We ate huge breakfasts of fried bacon and chicken, fish, grits and eggs, warm buttered biscuits and thick sweet molasses.

After all these years, I still remember.

‘The Separation of Even Primitive Public Toilets by Race’

WHAT I REMEMBER MOST, among the starkest contrasts between southern life and northern life for Black folk well into the 1960s, are the clear lines of racial demarcation in the South; the absence of modern conveniences; and the sense that time and progress had seemed, in some ways, to have left Mississippi behind.

I remember the first time I inquired about a bathroom. I had searched the house, but had not found one.

“Where’s the bathroom?” I asked, puzzled.

They laughed. “It’s outdoors, boy.”

Outdoors? Yep. Outdoors.

Where’s the toilet paper? They showed me the choice between newspaper and cotton.

I was also showed the way to the outhouse out back. It was my first encounter with entering the kind of makeshift porta potties, or wooden structures separate from a house or main building that cover toilets and that were largely used in areas where sewer systems were absent. I pulled the heavy stubborn door and was greeted by the heated blend of excrement and urine that stung my virgin nostrils. In time, I got used to it, although I kept my outhouse encounters short and sweet, so to speak, making my deposits into the liquid pit laden with doses of white lime, then fleeing through the door.

More than five decades later, I still remember.

What I remember about outhouses, inasmuch as they were once upon a time a necessary part of life, is that they were once a symbol of the depth of American apartheid and racial segregation’s low-down dirty shame: The separation of even primitive public toilets by race.

A National Geographic article recalls of that era: “Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, segregation laws, also known as Jim Crow laws, were instated throughout most parts of the American South to separate white and Black Americans after the abolishment of slavery.

“…Prior to Jim Crow, ‘Black Codes’ were introduced throughout the South starting around 1865,” the article continues.

That included segregating, according to race, everything from restaurants, to schools and transportation, to water fountains and public toilets, even outhouses.

“Making stops in unfamiliar cities or ‘sundown’ towns’ increased the risk of threats and lynchings,” the article continues. “Stopping in an unfamiliar place carried the risk of humiliation, threats, or worse.”

More than five decades later, I still remember, in part, because I’m old enough to have experienced it. At least to the extent that I spent a summer and other time in the Deep South. But what about future generations?

‘To Tell The Unfettered Truth’

REMEMBRANCE OF OUR STRUGGLES against racial segregation and oppression as a people, of our journey up from American slavery, of our valiant stride toward freedom, the Civil Rights movement and the historic truth about the atrocities and inhumanity inflicted on the bodies and souls of Black folk since our arrival to these shores as human chattel has never been more critical. Particularly amid the current attack on truth and the winds of revisionist history now sweeping the nation like wildfire.

In fact, just this week, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey signed into law SB129—a bill that prohibits public schools and also universities from funding or maintaining diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, or DEI.

Efforts to suppress Black history and to eliminate DEI programs in Florida have prompted the NAACP to issue a “travel advisory,” warning African Americans. In an Associated Press article last July, Derrick Johnson, the NAACP’s president and CEO, criticized Gov. Ron DeSantis’ “aggressive attempts to erase Black history and to restrict diversity, equity, and Inclusion programs in Florida schools.”

The issue is even more widespread, according to a 2021 article in Education Week titled, “Map: Where Critical Race Theory Is Under Attack”

“Since January 2021, 44 states have introduced bills or taken other steps that would restrict teaching critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism, according to an Education Week analysis. Eighteen states have imposed these bans and restrictions either through legislation or other avenues.”

The blatant push to water down, revise or completely erase Black history, in my estimation, is, in itself, racist. While the battle to prohibit such censorship in public school systems is crucial, however, so is the need to ensure the teaching of our history to our children for us and by us. That has never been clearer.

Whether it occurs by continuing the verbal tradition of telling of our stories from generation to generation, through books, movies and documentary films or other ways of modern storytelling—or some mix of all of these—matters less than our absolute commitment to teaching and preserving our history.

We must tell the unfettered truth about Black life in America—no matter who it offends or makes squirm in shame or discomfort. Deal with it. It happened. Our bodies and souls still bear the scars of racism’s pain. We must never forget.

But if our homes contain more video games than books on the shelves; if our children use their electronic libraries called smartphones for posting on social media more than for accessing the world of history, information and knowledge; and if we fail as a people to cherish, guard, protect and savor through ceremony, remembrance rituals and celebrations of our great history, then who shall we blame except ourselves?

Some years ago, I asked a group of Black elementary school children in a small town just outside Chicago if they knew who Jesse Jackson is. The classroom of more than a dozen children stared at me blankly with no apparent clue. Then finally a student waved his hand excitedly.

“I know who he is, I know who he is,” he said, self-assuredly.

“Who is he?” I asked.

The boy responded: “Michael Jackson’s brother!”

“Nope, I’m sorry. That would be Tito, Jackie, Randy, Jermaine, and Marlon,” I said, laughing on the outside, but crying on the inside.

I explained that Rev. Jesse L. Jackson was an American civil rights leader and icon who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; and headed Operation PUSH. A Black man who ran twice for the office of president of the United States. The man known for leading Black people everywhere in unison to declare boldly and unapologetically: “I am somebody!”

An Aged Wooden Door Speaks

NO MATTER WHAT THE states—or America at large—decide, it is our solemn duty to teach our history to our children and to our children’s children so that we may never forget.

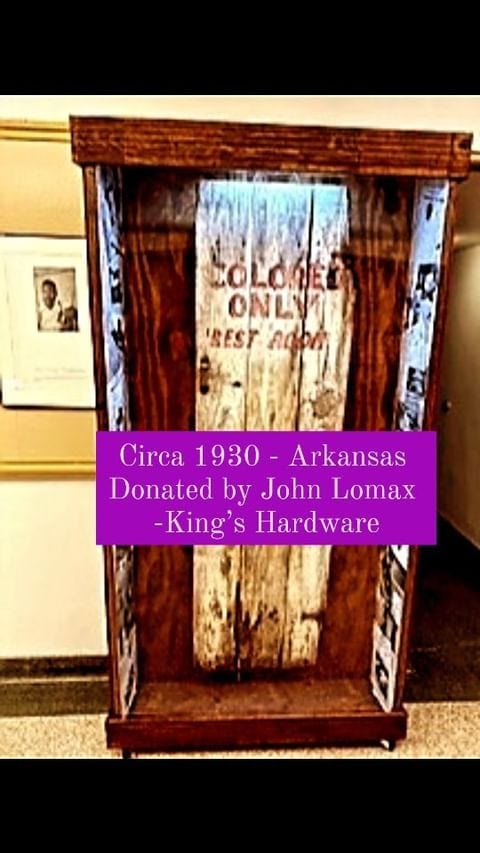

Recently, as my mentor and bonus dad Paul J. Adams III unboxed a relic that he wanted to show me without revealing beforehand the box’s contents, I fell mostly silent as the words “COLORED ONLY REST ROOM” were revealed, emblazoned in red on an aged wooden door.

The door, donated by John Lomax, of King’s Hardware, had been the entrance to an outhouse in the Deep South in the approximate 1930s. A remnant of darker days, a small testament of a bygone era and proof of what happened. A relatively small piece of evidence that cruel Jim Crow discrimination was not a figment of Black folks’ collective imagination.

I and others stood in Mr. Adams’ garage in amazement as he talked about the aging door—lingering somewhere between today and the memories of yesterday. Standing in the embodiment of a little Black boy born into segregation in Montgomery, Alabama. A living testament of the journey of Black folk from the struggle to the dream and still haunted by recollections of that sweltering summer day in August 1955, when, at age 14, he received the news about the lynching of another 14-year-old boy named Emmett Till.

“When I saw this, I just blew up almost,” Mr. Adams, now 83, said to us, studying the door and saying that he planned to frame the outhouse door and place it on display as a slice of history for students in the halls of Providence St. Mel School.

It is my alma mater, a school Adams founded in the heart of the hood on Chicago’s West Side, believing in the power of education and hope, and in the lessons to be learned from history. Since 1978, Providence St. Mel has sent 100 percent of its graduates to colleges and universities nationwide.

“That’s the real deal,” Adams told us excitedly as he stared at the outhouse door. “…When I saw this, I started crying.”

History can have that effect. Whether spoken from the lips of a conscientious dear mother. From the heart and memories of those who lived it—even from the soul of a man who was once an Alabama boy. Or whether history speaks silently from the aged wooden door of a segregated outhouse that now stands as a symbol of a time in America that we must never forget.

I still remember. We must always remember.

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com