A Timeless Chicago West Side Story: One Man's Journey of Faith, Hope And Clarity

The light from the flickering television gave way to their furry bodies. I stared into the kitchen, pulling my feet securely into bed. There were too many mice to count.

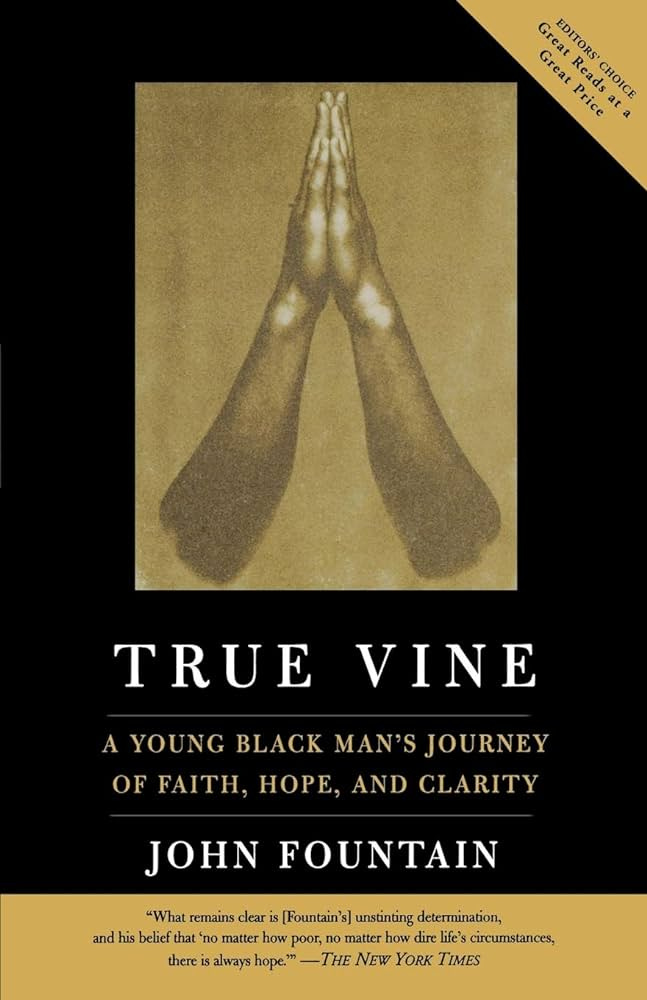

This week’s column is an excerpt from the author’s memoir, “True Vine: A Young Black Man's Journey of Faith, Hope And Clarity”

By John W. Fountain

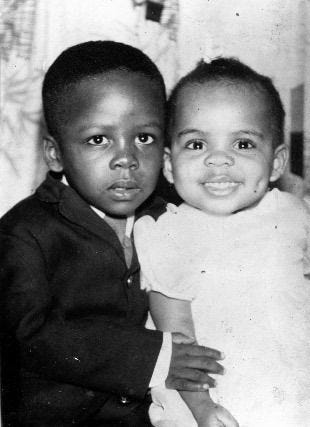

ANOTHER TRAP POPPED. I lifted the copper wire from the neck of the little gray mouse and slid it into the plastic garbage bag with all the other bloodied and disfigured corpses. Then I reset the wooden trap and climbed back into the bottom bunk with my anxious little brother. Jeff didn't know it, but I was just as afraid as he was. I have always been afraid of rats and mice, ever since the first time I spotted one scurrying through our apartment when I was a little boy. But I never had the freedom to show such fear. Somebody had to be brave. Most of the time it had to be me.

It was after midnight. I was 18, Jeff, 11. I was home from college on winter break, and we were trying to trap the little critters that ran amuck in our apartment when everything and everyone else stilled and the lights dimmed. Just when things got really quiet and dark, you could hear their little feet. Their teeth and nails ripped through food packages. They tiptoed across tin pots and dishes, rummaged through the garbage, gnawed at chicken bones, squeaked. By day, the apartment was ours. By night, it belonged to every creeping thing. It seemed as if there had been some unspoken agreement between the mice and us.

“Don't y’all mice come out in the daytime,” was the way I had imagined our agreement had been cut with the Head Cheese, who had squeaked back in agreement, “And don't y’all even think about coming into the kitchen at night.”

If you had the choice, you would choose to live with mice rather than rats. Rats were bigger and acted differently from mice. Mice scurried. Rats strutted, pimp-walked, came out in the middle of the day, stared you in the eye and dared you to say something. Mice were more agreeable.

Strangely, as my stepfather rounded the corner near home, I also wondered whether Komensky was a place where I belonged anymore.

WE WATCHED THE MICE under the glare of the old black and white portable television that sat on our bedroom dresser. The television’s nobs were long gone, worn out from turning and since replaced by a pair of pliers that worked just as well. We used a wire clothes hanger for an antenna. The picture usually showed well enough for us to watch television, which on Friday nights was a Creature Feature, a weekly show that came on after the news at 10:30 and showed horror movies like Frankenstein, Dracula and The Curse of the Werewolf. We sometimes jimmied the hanger on the television, contorting it beyond recognition. When even that failed to produce decipherable sound and picture, we slapped the television hard, either with a good whack on the side or a closed fist on top. When I was Jeff’s age, the glare and buzz of the television had rocked me to sleep at night. I’m not sure if that was because the light of the television gave me some sense of comfort since I was mostly afraid of the dark as a child. Or maybe it was because the voices that emanated from the television helped drown out the sounds of the mice that crept in our house for hours after midnight.

The Meeces—our pet name for them—sometimes seemed to be everywhere. Little gray shadows danced on the stove and in the oven, They darted across the washer and dryer with near bionic strength. They climbed on top of the refrigerator and dangled from the kitchen curtains. Their rubbery-looking tails always a dead giveaway. Between the mice and roaches, it’s a wonder that we even had room for us humans.

By the time we climbed out of bed on most mornings, the sun had poked through the dirty blinds, lighting up the kitchen. The visitors were gone, having crawled back inside their holes after a night of siege. We were always relieved. But I always felt a little queasy about putting my bare foot on the wooden bedroom floor, where I imagined one last mouse on his way back to his hole might brush across my flesh. After arising from bed some mornings, we would soon discover that the beady-eyed invaders had rumbled through our cereal boxes or had left their droppings on our pantry shelves. Half asleep, we opened the cereal boxes and a few roaches crawled out. Or sometimes there were holes in the bottom of the boxes or bags where the mice had barreled through and had their fill. After a while, we got used to it. At least we stopped crying.

But life at home had worsened in the four months I was at college. Either that, or escaping it for the first extended period of time in my life—other than a few short summer stints away—had only made things seem much worse. However bad it seemed before, there were never this many mice before, or this many roaches, nor was it this dark and depressing.

I wondered if my college friends had gone home to similar circumstances. I imagined they did not. And I felt sorry for myself, so sorry and depressed. As usual, there was enough of that to go around at our house even when there wasn’t much food.

A kind of dark coldness had hung in the air as I walked through the door a few days earlier, carrying my bags fresh from my first semester at college. My stepfather picked me up at the downtown bus terminal. It was busy as usual. The bus station always seemed to buzz with travelers and students going to and from college. Then there were the smelly homeless men and women and dressed-down pimps with roaming eyes who prowled the station for wide-eyed young girls who had run away from home and landed in Chi-Town. The ride to the West Side was uneventful, although I sat silently on the passenger side with mixed feelings, trying to reconcile life in my two worlds. And strangely, as my stepfather rounded the corner near home, I also wondered whether Komensky was a place where I belonged anymore.

Inside the hallway leading to our apartment, the air had the same stale and flat odor, the paint was still peeling. I walked up the wooden stairs, my footsteps and the squeaks announcing my arrival.

“Johnnnnn,” my sisters and brother screamed.

“Hey-y-y,” I answered, dragging my bags. “Hey, Ma.”

“Welcome home,” Mama said, smiling, although she seemed tired and drained.

Their eyes fixed on me as though I had been away at war and had finally come back home., and now everything was going to be all right. It was as if my mere presence breathed a fresh wind of life into the apartment, with its gloomy faded walls soiled by the soot from the kitchen space heater. It felt weird that my family seemed so happy to see me, not that they should not have been happy. But it was if I had made it back to the island where we had all been stranded. And though my one-man life raft had just barely sufficed for me, there was the sense that somehow I could help make life. on our island more bearable until a ship big enough for all of us came in. I was happy to see my family, too, but not to be donning my cloak of responsibility to try and make everything better—a burden that had been at the root of my adolescent migraines. But as much as my family needed me, I too needed something or someone to help me out of poverty’s quicksand.

I ALREADY HAD A LOT on my mind that December. If my computations were correct, and I knew they were, all of my partying and lack of study the first semester had landed me on academic probation. At best, I was on the high end of a D average and I felt pretty troubled about it all. Not to mention ashamed. I decided not to tell Mama. It wasn’t that she would smack me or give me a good whipping. I had gotten too old and big for that. If she really got mad, I figured she would probably curse me out, which was even worse than a whipping.

Later that winter break, I was in the living room and mama somewhere in the rear of the house near the kitchen when suddenly she screamed, then summoned me.

“Yeah?” I said, hurrying to her.

“What’s this?” she said, holding a small white sheet of paper that looked familiar. The paper came into focus.

“My grades,” I responded, shocked to see them dangling from Mama’s hand as she stood, leaning on the broom.

I had actually received my college grade report in the mail weeks earlier and had hidden it after it confirmed my fear that I was on academic probation. And. In danger of being expelled from school/. Somehow the grade report must have fallen out of my drawer and onto the floor. Either that, or Mama had sifted through my dresser drawers and discovered it. Before, whenever she had asked me why I had not received my grades in the mail, I told her I didn’t know. Now there was no more hiding.

I stood there, my heart pounding., waiting for Mama to pull out a belt and whup me the way she did when I had done something bad as a child, or just curse me out. Seconds passed. It seemed like minutes. And still there was no lecture, no slapping or beating. Then suddenly the tears began pouring down Mama’s brown face. It was an incessant river that made me wonder if and when she would ever stop crying. She just hung her head, slumped and sobbed. I never saw Mama cry like that before, never saw her so wounded and hurt. She didn’t say another word. She didn’t have to. I shuffled away feeling punished enough.

THE MOOD INSIDE OUR apartment on Komensky that December was like the long melancholy wail of Miles Davis’s horn. As Jeff and I turned the lights off in the apartment and went to bed, the fuss of the television was all that could be heard until the tin-tipping of the mice began. It grew louder, more repetitive, like Morse code.

“Man, what’s all that noise?” I asked, knowing it had to be mice, but not wanting to believe it could have gotten so bad in a few months.

“It’s the Meeces, man,” Jeff replied, peering out of the bed at the mice crawling on top of the kitchen sink under the cover of a mostly dark kitchen. “Them four-legged soul brothers,” he said, laughing.

The light from the flickering television gave way to their furry bodies. I stared into the kitchen, pulling my feet securely into bed. There were too many mice to count.

“Gol-leee mannn, look at all them suckers,” I said my skin starting to crawl.

We laughed and laughed some more. Then we decided to have some fun. We climbed out of bed and flicked on our bedroom light first, then the kitchen light. The mice scattered. We went to my stepfather’s toolbox and grabbed a couple handfuls of metal staples and some rubber band, then turned out the lights and jumped back into bed. The mice quickly reemerged. We lopped the rubber bands around our index finger and thumb the way Michael and I had done on those Sunday mornings at True Vine and fired away. Our shots ricocheted off the kitchen appliances, dinging the washer, the dryer, and the refrigerator.

“did you get ‘em, man?” Jeff shouted.

“Nah, man, he got away,” I said. “Man. I’m gonna kill them suckers.”

“Me too,” Jeff said. “Gimme some more of them staples.”

“Man, it seem like a million of ‘em,” I said, firing off more rounds. Pop! Pop! Pop!

“Yeah,” Jeff said, laughing. “It’s a lot of ‘em…” Pop! “Look at that sucker on the stove.” Pop, pop! Pop!

We quickly discovered that the mice were both too fast and too small and our aim too imprecise. And after a while, I stopped laughing. In fact, we both stopped laughing.

“I can’t believe this, man,” I said, scratching my legs and arms. “I can’t believe the mice done got this bad.”

They were so bad that (our sister) Net had picked up her shoe one morning only to discover a mouse had taken up residence there. They also occasionally climbed atop her bed and scurried across the blanket. She was half afraid to sleep at night.

“So, what Daddy do about it?” I asked Jeff.

“Nuh-thin,” he muttered and shrugged.

“Nu-thin?” I said angrily. “Man, how come he ain’t do nuh-thin?”

Jeff answered. “He put some traps out, but he ain’t catch none.”

I could not believe it—yes, I could. Still, it seemed next to impossible to understand why my stepfather had not ridded the apartment of the mice. It wasn’t enough to have simply set the traps and allow the mice to still exercise dominion. Why hadn’t he caught them? Why hadn’t he done this simple thing to make things better for his family? Why, even while the mice were doing the Boogaloo in our kitchen, was he not even home but out somewhere, who knows where, doing who knows what? It was the same way many nights on payday, when there was nothing to eat and hours turned into days without a word from him until Monday when he showed up a few hours before dawn with excuses but nothing to eat. Why tonight wasn’t he here with us? Where was he? Where in the hell was he? And why should I have to catch these mice? Why always be the man?

I got mad.

“I’ll kill ‘em,” I said. “I’ll kill ‘em.”

I rushed out of bed again and flicked on the lights. Behind the dryer and the refrigerator sure enough, I found the traps that my stepfather had set to no avail. They were still baited. But the cheese was as hard as a rock. If I were a mouse, I thought, I would not nibble from these traps either. I cleaned the hardened, cracked cheese out of the traps, then soaked the traps in the bathtub in water. I did so, thinking that maybe the traps carried a human scent from being handled and needed to be cleaned, so to speak. I don’t know how I came up with this idea. Probably it was from watching too much television. Anyway, I got a couple of strips of bacon from the refrigerator and rubbed it on every inch of the traps, then fitted a few small pieces into the bait hook. I placed one trap behind the dryer and another behind the refrigerator. We climbed back into bed and waited for action.

A few minutes passed. Then pop!

“We got one of them suckers!” I said, dashing out of bed with Jeff close on my heels.

Sure enough, there was a mouse in the trap, his head partially severed by the metal wire. I emptied the trap and reset it, blood-stained and all., without rebaiting. It popped again and again and again into the morning light.

In the end, there were twenty-three corpses in all. Mama was ecstatic the next day when I told her I had caught all the mice and was even happier that next night when the kitchen was still and quiet after the lights dimmed and we’d all gone to bed. I also went out and bought a can of Raid and killed a few hundred roaches that fell from the ceiling like raindrops and were swept into a pile, then properly disposed of. Mama was so happy. So was I, except I knew that old problems, no matter how joyous the reprieve, would eventually come creeping back into our lives. Just like the mice.

#JusticeForJelaniDay

Email: author@johnwfountain.com