A Commencement Letter To My Black Son And Others: "You Are Not An Imposter"

'Be unapologetic and always humble, even as you move forward to the next journey, wherever it leads. Follow your heart. To thine own self be true.'

By John W. Fountain

Dear Son, amid excruciating pain from having aggravated an existing foot injury, I contemplated not traveling to New York for your graduation from Columbia University. The thought, however, was fleeting, like the years since I first cradled you as a newborn in my palms. The time seems to have evaporated like wisps of steam. I had to be there. I could not fathom otherwise.

I feel just as compelled to write to you here now words that you might not yet fully comprehend or cherish. To express to you the depths of my pride, my love, my great hopes, and also my fears for you as a man—young, gifted and Black—ending one journey and yet embarking on another in an America that still holds cruelty and lethality for Black bodies and dreamers.

To exhort you and other Black sons like you, commencing in this season of your lives your individual journeys as men, to be of good courage, to continue to fight the good fight, like your great ancestors on both your father’s and your mother’s side, who persevered through American chattel slavery.

Indeed our ancestors’ cheers resonated from glory as you walked across the stage of an Ivy League university, a symbol of possibility, hard work and faith. As proof that God answers prayers that still linger in the atmospheric mist, pregnant with promise, somewhere between the earth and the heavens.

I write as a father who recognizes his own mortality, with the earnest hope that my words—and if perchance any wisdom to be gleaned from them—will speak long after I have taken my last breath. With the intent that even if you will not have my physical presence, you will always have the words of my heart, your father’s words. It is too precious a thing to leave to chance.

‘Climb Higher, Go Farther, Dream Bigger’

BEING THERE. THAT HAS been my aim since before you took your first breath, since that day a nurse searched your mother’s belly with the ultrasound wand for evidence of our new baby’s gender, “It’s a boy!” I exclaimed.

I remember, like yesterday, first setting my eyes upon you, fresh from your mother’s womb, dangling naked caramel brown with a full curly head of ebony-colored hair on that Ides of March in 2002. I snipped your umbilical cord with the doctor’s stainless-steel scissors. Studied your wet body from head to toe with wonderment. I remarked in astonishment to your mother that this—you, unblemished—could not be my son… That you were too perfect to be my son. I felt, even then, like I did not deserve you.

And yet, I have always endeavored to cherish and, with meticulous intent, to be a good caretaker of, the gift of you.

Indeed you are my “joy boy,” the last of three sons—the other two born in my youth (John-John when I was 17 and Rashad when I was 19) and whom I also love dearly. You are the son of my more latter years, born when I was six months shy of 42.

Your brothers were beneficiaries of my youth, although as a young father I always wished I could have given them so much more materially. It pained me greatly when I looked at their feet once and their shoes had become so tight that their toes bore corns.

I remember back then, coming face to face with the reality that I had no savings, no silver lining, no life insurance, nothing, except welfare. And I reasoned that I—and my children—would be better off if I were dead. Except I had encountered the scripture that said, “A man’s wealth consists not in the abundance of things he possesses.” I embraced God’s word and sought to give my children all those precious and priceless things that fathers can provide, which don’t cost a dime: love, presence and time—despite my inevitable share of mistakes amid my failings, shortcomings, inexperience and inadequacies.

I want you to know that I’ve always tried to let my love for my children—particularly amid the incurable agony of abandonment by my own father who gave me only his name and DNA—push me toward striving to become a better man. I reenrolled in college after having dropped out years earlier determined with a new fire and motivation to make something of myself and to be a better producer and provider for my family.

In fact, it was exactly 40 years ago this spring, after having dropped out of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, that I began the final push to return to school there that fall of 1984—this time with a wife and three small children in tow.

I was filled with fear and uncertainty as we journeyed like the Beverly Hillbillies down I-57, from Chicago toward Champaign. In fact, I marvel today at that 23-year-old young man—a year older than you are today—who dared venture into unchartered territory unenviably carrying the consumptive weight of the world on his shoulders under which he sometimes collapsed. I am grateful that this was my cross to bear, and not yours. And yet, every man has his own.

It was undoubtedly difficult for you at times to feel like you needed to have a “tales from the hood” story of poverty, absentee fatherhood and struggle like mine. Difficult, in one sense, to have grown up in a comparatively pristine quiet suburb, middle class with two parents, no neighborhood street gangs, no broken glass or gunshots—which is the way life should be for every child.

Except in Black culture, where street cred, bravado and being gang-affiliated, or at least a bona fide boy in the hood—particularly for young Black males—is still too often esteemed by our people over being book smart, clean-cut, respectful, academically inclined and gifted. Nerds still get no respect. Except nerds rule the world.

But I digress… As I have told you before, “You don’t have to have a hood story to have a good story.”

I and so many other Black fathers climbed that less than crystal staircase so that our sons—and daughters—wouldn’t have to. Our pain was for your gain.

You owe no one an apology for your inherited socioeconomic circumstance or opportunity that your father worked for so that your road might be less perilous in some ways, less uncertain or not filled with the same potential pitfalls. But know that your own individual road to success has been paved by your hard work, talent and sacrifice. You alone earned it.

And I continue to implore you to stand on my shoulders—on our shoulders—and climb higher, go farther, dream bigger.

The Quicksand of Imposter Syndrome

YOU ARE A GIFT. A brilliant mind. A scholar and a leader. With that in mind, be unapologetic and always humble, even as you move forward to the next journey, wherever it leads. “To thine own self be true.”

I have always embraced your proclivity—despite your love of running and fitness—toward nerdy things. Like robotics, mathematics, engineering and all things science, and your affection for Tony Stark, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and Elon Musk, even if you have felt in some circles, among some peers, “friends” and others that you were not accepted. Or that you did not meet their perceived physical prototype of someone who was “smart.” Or like in high school when you gained admission to the National Honor Society as a sophomore, about which some of your classmates circulated the hurtful lie that your parents had finagled the honor on your behalf.

I remember your angst, your tears and discouragement when at times your deep chocolate skin, amongst our own, was deemed “too dark.” That, at times, your use of the vernacular caused some to cast aspersions. Your very presence on Columbia’s campus in your six-foot-tall Black frame sometimes caused spoken assumptions that you must certainly be a student-athlete. Nothing would be wrong with that were it the case. The issue is that the same assumption isn’t made about 6’, 5” young men who are white, or Hispanic, or Asian.

As a Black man in America, I understand how it feels to feel profoundly and discomfortingly out of place—a square peg in a round hole. To be glared at. Stared at. To eventually begin to question your abilities, your purpose, your dreams. To have your psyche battered. Your manhood, even your Blackness, challenged. To have to work harder, to be better, to feel like you always have to prove yourself.

To feel like “they” don’t understand you. And that “they,” too often, is “us.”

To come to recognize gaps in your learning—even amid a solid educational foundation—in a public school system that 70 years since Brown v. Board of Education remains separate and unequal. To realize that white students have so much greater access and educational opportunities. I know how easy it is to slip into the quicksand of imposter syndrome.

So let me reassure you, henceforth and forever, that you are not an imposter. You never have been. You never will be.

Your acceptance four years ago to several Ivy League and other top universities was not a fluke. Your one digit less than perfect on the ACT was not happenstance. Neither your 99th percentile national standardize test score in elementary school, or your persistent record of achievement both inside and outside the classroom. Just as authentic is your compassion for others, and all your other gifts beyond your intellect. Among them your burning desire to make a difference in this world. But whatever your grades or test scores, they are not the sum of you.

It was your heart that led you to declare as a little boy that you would someday become an engineer and inventor. Not for fame or fortune, but to help your cousin Titus, born with a physical disability—and also potentially to help so many others.

That alone makes you a special son. No, it does not make you better than anyone else’s son who causes their chests to swell with pride. And yet, it overwhelms me to know that you are my son.

Once upon a time, when money was low and my future seemed bleak, my grandmother urged me to count my blessings. “I know men who would give their arm for one son, you have two,” she assured me.

I now have three. And I know that a man would give even his life for a good son.

May All Your Dreams Come True

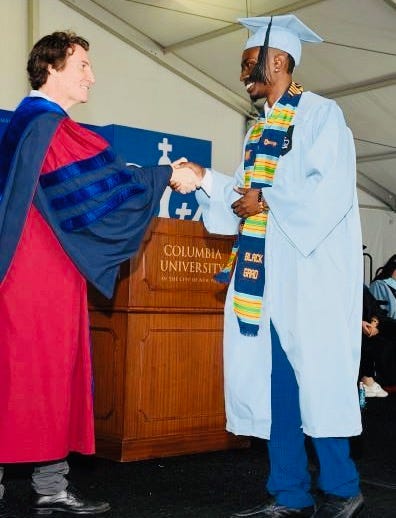

I ARRIVED IN NEW York City an hour before your graduation from the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science and made my way to the Baker Athletic Complex—relieved and ecstatic that despite the university’s cancellation of general commencement exercises, due to on-campus protests against the war in Gaza, that individual schools were proceeding with ceremonies.

The family was already seated in the disability section because of grandma, 87. It was a good thing for me too because I was hobbling in great pain.

I resistantly, though necessarily, took a seat in a wheelchair and was pushed up the hill to the entrance, where a sea of graduates robed in Columbia blue and waving inflated red hammers in celebration ascended. I pulled out my camera, hoping I had not missed your gallant entrance.

I had. But not the ceremony. Not the chance to see my boy walk across the stage, which had been cancelled in high school due to the COVID shutdown.

And yet, here you were, four years later, having completed your first year of college virtually at home, now poised to matriculate from a school I could only have dreamed of attending—and with a degree in mechanical engineering with a minor in biomedical engineering. Having explored the creation of artificial muscles, theories, laws and concepts beyond my understanding.

Having completed your senior project with a device that supports people with neurodegenerative diseases by detecting tremors and suppresses them, allowing the person to move their arm and engage in essential movements. Having completed years of summer internships, and having adjusted to the rigors and difficulties of life in these times. And yet, having emerged with the core of who you are still intact, still smiling and ever optimistic as you decide what’s next.

Remember: Don’t take the money and run. Follow your heart. If a job wants you now, they’ll want you even more later with more education and expertise… (I will write to you more later.)

I was soon wheeled inside to commencement. I fidgeted, filled with a mix of emotions and thoughts that drifted between yesterdays, today and tomorrow.

How over the last four years, some of my friends have purchased new cars, taken lavish vacations, lived their best lives on the fruits of their labor. Whenever they asked if and when I was going to buy a new car, I told them that my financial commitment was to seeing my son earn an Ivy League education and to getting a start in life on his own debt free. For you are my best investment, my heart, my hope. The best of who I am and have been and the best of what I could ever hope to be.

Not lost on me as I watched you climb the stairs to the stage was that you are the hope and the dream of the slave. That the blood of your once enslaved great-great-great grandfather flows warm through your veins.

That a ghetto boy like me could be gifted with a little boy, with a son—now a full-grown man—named Malik. That you helped restore for me the joy of fatherhood. That you are a son who did everything I ever asked him to do. A son who cares deeply about his father—even if you COULD call me a little more often, if only to say, “Wassup, Dad?” (smile).

I snapped photos as your name was read, watching you from a distance as you strode deservedly across the stage in your Columbia blue. My heart swelled with sweet pride. And my soul cried.

Congratulations, son. May all of your dreams come true. Congrats too to your friend Jalen Kendrick, friends since First grade, on his graduation from the University of Rochester. Onward and Upward.

Love forever, DAD

Email: Author@johnwfountain.com

Congratulations John to your family and especially Malik. You have given him a gift of a lifetime He is blessed to have a family that love and supports him A precious gift ❤️